At Afton Villa near St. Francisville, Louisiana, four Classical figures carved of Italian stone mark the place where the house once stood. (Photo: Courtesy of Afton Villa Gardens)

Most Gone With the Wind fans swoon over the enduring love story, the spirited optimism of Scarlett in a restrictive society, and the detailed descriptions of how the Civil War ravaged the South. But gardeners might notice something else—the long, shadowy avenue of trees leading up to Tara; the red-clay Georgian soil; the high-walled Charleston garden where Scarlett visits her relatives after her husband has died; and John Wilkes’ rose garden at Twelve Oaks plantation.

All across the South, massive, ornate plantation homes were constructed with money generated through a slave-driven economy. During the antebellum period (the years before the American Civil War, from approximately 1812 to1860) Greek Revival, Classical Revival, and Federal-style homes were very much in vogue—imposing, grand estates that were symmetrical and box-like, with central entrances flanked by stately columns. You’d assume with all this grandeur, the owners would have gardens to match.

But when author James Cothran set out to research his book, Gardens and Historic Plants of the Antebellum South (University of South Carolina Press, 2003), he was in for a big surprise—many plantation homes had no decorative garden at all.

“I started out thinking that everyone would have had a garden, particularly if they were upper class, but that was more an exception than the rule,” Cothran says. “Oftentimes people put more effort into the house than the garden, and that’s still true today.”

Garden Patterns

Low rows of boxwood and flowering plants create a formal garden called a parterre, a design inspired by the gardens of Europe. (Photo: Courtesy of Afton Villa Gardens)

Homes that did sport elaborate gardens tended to follow a similar pattern, regardless of whether the house was in the middle of a city or a gentleman’s farm: The design was geometric to complement the classical and formal lines of the house. On a working plantation, the decorative garden was usually front and center and possibly wrapped to the sides of the house, but the rear was reserved for more functional uses, like outbuildings for servants’ quarters, cooking, and kitchen gardens. “The back yard was a very utilitarian space,” Cothran explains.

In rural areas, visitors would approach the house and front garden via an avenue of trees, usually live oaks (so named because they remain green throughout winter). With their stately, curving branches, often dripping with Spanish moss, these trees offered a ceremonial entrance to the plantation, focusing visual attention on the house itself, says Cothran.

The front ornamental garden also provided a segue to the house. Gardens were usually parterres (French for “on the ground”), a formal-style garden of planting beds edged with patterns of clipped boxwood and symmetrical gravel, sand, brick or crushed-seashell paths leading the way.

A long avenue lined with towering live oaks—peppered with Spanish moss and flowering shrubbery—was a staple of antebellum plantation garden design. (Photo: Courtesy of Afton Villa Gardens)

Afton Villa, once the most imposing estate in West Feliciana Parish near St. Francisville, Louisiana, has a winding, half-mile-long drive of more than 250 live oaks underplanted with azaleas. The house itself was destroyed by fire in 1963, but the current owners, Morrell and Genevieve Trimble, spent 20 years restoring the 250 acres of gardens to their former glory.

When Susan Barrow built the 40-room Gothic-style mansion in 1849 (an atypical style for the day, but she wanted to reproduce the mansions she had admired while traveling in France), she added manicured French-style gardens as a formal enhancement to the front of the house. Below the mansion, a series of seven terraces led to a ravine, where Mrs. Barrow’s greenhouses stood.

Nearby at Rosedown Plantation, a 374-acre spread in St. Francisville, a 660-foot-long oak-lined drive leads to the circa 1835 Federal-Greek Revival-style house and its surrounding gardens. Unlike most gardens of the period, Rosedown’s gardens actually overshadow the architecture—quite a feat considering the grandeur of the house, with its six majestic front columns, expansive porch, and stately upper balcony. The original owners, Daniel and Martha Turnbull, toured Europe after their marriage in 1828 and were inspired by the formal elements of Italian and French landscapes, as well as the romance of English gardens. In the 1840s, the Turnbulls hired a landscape designer to create the gardens at Rosedown, which became Martha Turnbull’s passion for the next 60 years.

The Plants and Their Origins

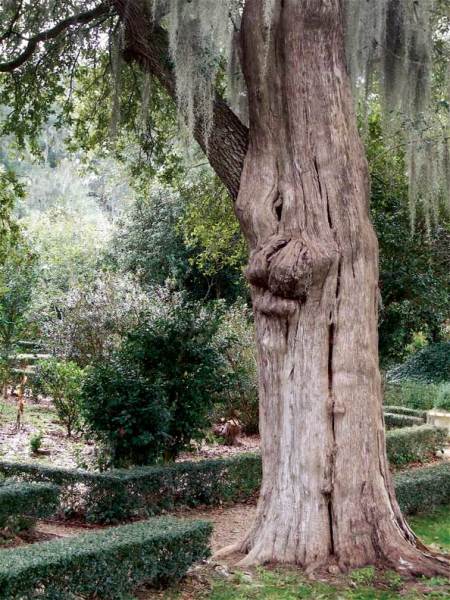

Because they are fast-growing trees, live oaks can have massive trunks. (Photo: Mary Hughes)

Many plant species used in Southern antebellum gardens were newly imported to America, so they were novel at the time. But today most are so common in the South that we tend to think of them as “Southern” plants.

“Boxwood was always the mainstay, usually English box, which could be clipped,” Cothran says. In the 1830s and ’40s, many new plants were introduced, including azaleas, camellias, cryptomeria, crape myrtles, and other imports from China and Japan. Other typical Southern-garden plants are still widely used: magnolia, hydrangea, sweet olive, and flowering seasonal bulbs.

“Many of these species were very adaptable to the Southern climate, so not only were they showy and unique, they performed well,” Cothran says.

Southern homeowners appreciated imported plants for another reason: They were a status symbol. “The plants were a hallmark of the Southern garden, because they made the gardens different from Colonial gardens,” Cothran explains. “The palette of plants in the South was much broader.”

Architectural elements such as a brick wall and statue add focal points to the geometric precision of the gardens at Rosedown Plantation. (Photo: Mary Hughes)

Maintenance Issues

Antebellum gardens like Rosedown and Afton Villa demanded almost constant maintenance. The boxwood hedges in parterre gardens needed frequent trimming, and the paths had to be swept of debris. “These gardens required a fair amount of attention,” Cothran says. Interestingly, many antebellum Southerners didn’t have lawns because they felt they were difficult to maintain. Even now, a plant-encrusted garden can be easier to care for than wide swaths of green grass in the long run.

If you’re thinking of installing a parterre garden, don’t be daunted by the work. Boxwood hedges do require frequent trimming, but creating a border of stone or a low-maintenance plant like mondo grass (Ophiopogon japonicus) requires little work once it’s established. Dwarf English box (Buxus sempervirens ‘Suffruticosa’) only needs pruning once a year. The parterre can be planted inside with seasonal bulbs, shrubs like azalea and crape myrtle, and small trees like star magnolia (Magnolia stellata).

In real estate, they say it’s all about curb appeal. You may not be able to plant 250 oak trees in a long, winding avenue, but if you’re restoring your home to its historic potential, don’t forget the outside altogether. Make a grand first impression, and people will beg to see what’s inside.

Gretchen Roberts writes about food, homes, and gardens from her 107-year-old Craftsman-style house in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Online Exclusive: Plan a visit to an antebellum garden with our guide.