Landscape designer Janice Parker added a pergola for structure. (Photo: Neil Landino/Courtesy of Janice Parker Landscape Design)

If you own or are planning a new home, chances are its architecture derives from some historic style: Neo-Georgian, with white front columns; adobe—long, low, and close to the earth; Shingle Style— wooden, rambling, but balanced in an asymmetrical way. What type of gardens should surround structures like these?

Surprisingly enough, the answer may lie in a modified type of formal garden, one that takes the best elements of the past and adapts them for today’s living—a looser version of the style that was common a hundred years ago and then disappeared with the onslaught of modernism in the 1950s. Now, before I hear any objections, consider for the moment that no word in the garden vocabulary is more misunderstood than “formal.” Almost inevitably, when I suggest to a client that some sort of formal approach might be appropriate, the response is: “Oh we really don’t want anything too formal in this garden; the house (or our lifestyle) doesn’t warrant it.”

This almost innate reaction against formalism, I believe, has its roots in the modern American predilection to eschew anything that might limit personal comfort or freedom. Within the last 50 years, and mostly for the better, we have adopted a less and less formal style of living, to the point that when one suggests that a portion of the landscape might be formal, the only vision the owner imagines is that of uncomfortably dressed ladies and gentlemen perched on hard, unyielding garden furniture sweating through interminable teas.

Stone walkways make a beautiful addition to the perennial garden. (Photo: Elenathewise/Fotolia.com)

Equally incorrect is the idea that formalism in gardens is only appropriate for grand mansions. In reality, “the formal style” was one of the earliest to be used in this country, dating back to the gardens of Plimoth Plantation and Jamestown, and has suitably accompanied homes as diverse as simple country cottages and the mansions of Newport.

The entire misconception about formal gardens arises from the word “formal,” whose connotation has become so potent as to incorrectly rule the definition. What we are actually talking about when we use the term “formal” is a garden that—in plan layout, at least—has a fair amount of symmetry and orderliness, as opposed to completely natural or wild.

Potted topiaries add interest to a grouping of garden benches. (Photo: Klimax Foto/Fotolia.com)

The organizational language of these formal gardens is of hardscape: walkways, fences, walls, gazebos, pergolas, arbors, balustrades, fences, stairs, etc. (Which is one reason that some people refer to formal gardens as “architectural” gardens, a term that is something of a misnomer but serves to illustrate a point.) This hardscape, which must invariably echo the style and material of the house, serves to extend the built environment out into the landscape, providing a container to hold the plantings, in much the same way that a good frame completes a painting. Structure also helps organize a garden internally: For example, a gazebo may serve as the central focal point of a vista, or a pair of flanked pergolas might form the perimeters of the flower or vegetable garden.

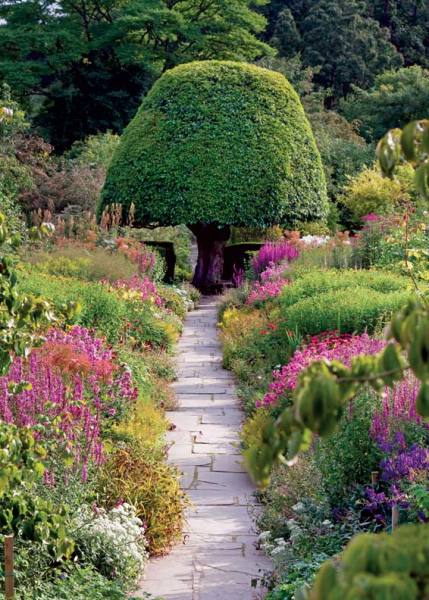

I know, I know: Some of you are already worried that the overall look of the type of garden I am proposing will be too fussy, too “formal.” This is not necessarily the case. What must be stressed here is that the strict geometric relationship between the house and garden, and within the garden itself, is really most noticeable when one looks at the plan in flat view. The bones of the garden—the paths, terraces, focal points, pools and so on—are indeed laid out in a rather rigid ordered and geometric way, and seem rather stiff when viewed solely on paper. How the garden is actually planted, however, may be as carefree and loose as a cottage garden (which most people think of as very natural, but is, in fact—with its orderly square beds and central focal point—quite “formal”), or conversely, the planting can be as tight and restricted as that at Versailles.

A sculpted tree at the end of a walkway is a stunning addition to the garden. (Photo: Ruth Black/Fotolia.com)

Remember, too, that the first order of nature is to obfuscate the line. Within minutes of installation, things begin to soften: dirt tumbles over a newly placed edging, plants begin to creep and crawl, patinas begin to form. The entire picture begins to move out of focus. This is, of course, part and parcel of the plan, but if you begin with a framework that is overly soft and mushy, you’re soon left with an overgrown mess. If you embrace geometry at the beginning, chances are that the result five or 10 years down the road will be the delightful form of controlled chaos that’s the essence of every truly successful landscape.

This then is the essence of what I could call The New Formalism: taking advantage of the many benefits of unity and symmetry that architectural-style gardens offer us, and adapting the plan and planting to the degree of “formality” that fits your lifestyle. If you prefer a box-edged garden with fountains and borders, or if you desire a wide open landscape with ample space and a quiet, simple palette, bravo! You can have either within this formula. The important thing is not to turn away from the sense and wisdom of a formal approach simply because it seems at first glance to be too stiff or rigid. In the garden, you control the degree and amount of formality, and are free to pick from a wide range of related architectural elements to suit your personal taste and lifestyle. What could be more pleasing than a garden founded on firm, classic design principals, yet customized to your personal needs and tastes?