Tanglewood Conservatories of Denton, Maryland, custom-built this ornate glasshouse onto a renovated carriage house.

People who live in glass houses, as we all know, shouldn’t throw stones. People who want glasshouses, on the other hand, are just a stone’s throw away from a mind-crushing array of decisions.

The basic design of greenhouses and conservatories has changed so little over the last century that it’s no problem to find a style that’s old-house appropriate. You can buy a kit greenhouse similar to ones William Randolph Hearst ordered in the 1930s if you want to feel like Citizen Kane. If you really are flush, you can have an architect design a custom conservatory with over-the-top Victorian detailing. You can build green and have a new greenhouse created from historic parts. If you’re truly lucky, you may already have an old greenhouse or conservatory that can be restored with relatively little skill.

Some Semantics

The words greenhouse, conservatory, solarium, and sunroom have all been used interchangeably, depending on time and place. As a rule though, greenhouses are architecturally simpler but technically more complex buildings, intended for the winter survival or propagation of plants—perhaps to nurture strawberries for consumption in January. Conservatories can be sprawling structures built for ostentatious show of rare tropicals, or glass-walled rooms attached to houses, intended primarily for the pleasure of people.

Orangery was an early term for a conservatory, since this subtropical fruit was all the rage when first discovered by residents of temperate climes. There’s evidence that Pompeians were growing oranges behind mica windows in the 15th century before their run-in with Mount Vesuvius. Probably the world’s best-known orangery is the one Louis XIV built at Versailles in the last half of the 17th century.

Three greenhouses at the Lyman Estate in Waltham, Massachusetts, include this 1804 Grape House, containing vines started from cuttings taken in England in the 1870s. (Photo: David Bohl/Historic New England)

Some early greenhouses and conservatories looked like ordinary rooms with a disproportionate number of windows-masonry structures with a solid roof and a stone or packed-earth floor to stand up to moisture and plant clippings. In the 1700s a common design was a lean-to of south-facing glass with a brick wall to the north.

Around the turn of the 19th century, the availability of cast iron made possible stronger structures with more sash. In 1816, English horticulturist J.C. Loudon invented a wrought-iron sash bar, less brittle than cast iron and cheaper than wood, which could be curved for glass domes. Loudon championed ridge-and-furrow glazing-what amounts to corrugated glass. With the ridge running north-south and panes facing east and west, greenhouses would get more gentle sun than with a flat southern exposure.

Because England taxed glass by weight until 1845, individual panes were still small and thin. Joseph Paxton, gardener to the Duke of Devonshire, seems to have bided his time until the glass-tax repeal before designing and building his famous Hyde Park Crystal Palace in 1851. Erected in 22 weeks, it covered 19 acres.

A restoration team at Hearst Castle is completing work on the second of two neglected greenhouses. One lacked a foundation; they built one, then buried it so the structure would look original.

The industrial prowess of the Victorian era easily accommodated stylistic excesses; conservatories got Gothic, Moorish, and even Anglo-Japanese touches. The structures often represented what one authority called a battle between architecture and horticulture. The Crystal Palace itself was unheated, and as the amount of glass in these buildings grew, better temperature control became imperative.

More humble early gardeners sheltered their crops in sash pits heated with decomposing manure or vegetable matter. The Dutch were among the first to heat larger greenhouses, using charcoal braziers. A common technology in the 1700s, both in the mother country and America, was hollow walls or flues that ran under the floor, allowing hot air or smoke to run the length of the building from a brick fireplace on one end to a chimney on the other.

By the late 18th century, the British were providing plants with both heat and humidity by steaming them with perforated pipes laid under stone or rock. Steam gave way in the mid-1800s to hot water heat. Especially efficient were the cast-iron boilers patented by Lord & Burnham in the 1870s, which could go without tending through an entire wintry night. These advances-by such other names as Hitchings, Pierson Sefton, American, Metropolitan, National, Foley, Lutton, Josephus Plenty, Ikes Braun (IBG), and Rough Brothers-created a boom in both private (at least for the wealthy) and commercial greenhouses.

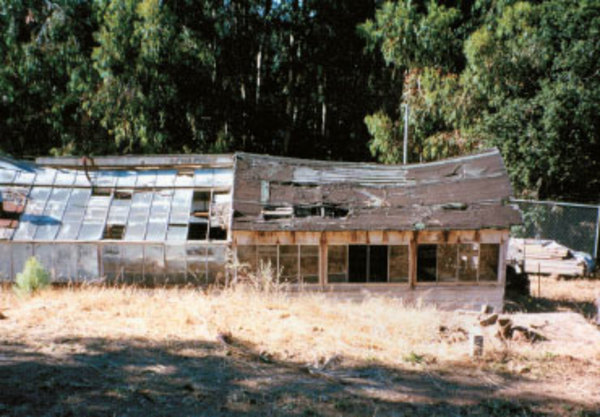

The heyday of greenhouse construction ebbed with World War I, when many of the factories (including Lord & Burnham) were given over to munitions. As fortunes waned during the Depression, many of these grand structures were torn down or left to the forces of nature, and only Rough Brothers and National (now marketed by Nexus Corporation) are still in business.

From Dream to Reality

If you’re thinking of buying or building a greenhouse or conservatory, it’s imperative to know what you want. Do you see yourself entertaining guests in a glassed-in room with parquet floors where a few ficus trees manage to remain presentable? Or do you want to propagate rare orchids and staghorn ferns?

Mark Ward builds greenhouses, like this one on Brian and Kathy Hollen’s circa-1910 Virginia home, from recycled parts. Ward believes that old parts such as this vent wheel have more charm and integrity than new ones.

Jim Smith and Mark Ward, who make their living restoring and rebuilding old glasshouses, say a lot can go wrong on both ends of the economic scale. “There’s an inherent conflict of interest,” says Smith, “between plants and oriental carpets.”

Smith was formerly head of restoration at Rough Brothers in Cincinnati and now operates his own company, Montgomery Smith. He’s been involved in such huge projects as the U.S. Botanic Garden and the Biltmore Estate and New York Botanical Garden conservatories. He also consulted on the restoration of the 1810/1903 greenhouse at Oatlands Plantation (a historic property outside Leesburg, Virginia), a relatively modest 33′ by 57′.

Avid gardeners wanting a small but historically detailed greenhouse can be disappointed by kits that yield what Smith describes as little hybrid Victorian pavilions with double ogee roofs that provide neither adequate venting nor shading.

Yet he’s also rescued a New England gardener who spent a small fortune on top-of-the-line growing benches and temperature control, only to invest in window sash more appropriate for a solarium. With no ventilation, heat and humidity were deteriorating the structure within six months.

Another client of Ward’s who, like the Hollens, has a heated pool in her greenhouse says it helps warm it—not to mention provides humidity for plants.

Shortly after earning his degree in social psychology 28 years ago, Mark Ward took on an intern project for a community garden. When the project fizzled, he found himself proud owner of the remains of a 3,000-foot commercial greenhouse. On his own, he learned that old glasshouses are considerably easier than Humpty Dumpty to put together again. For a while, he limited himself to reconstructing four or five greenhouses a year within a couple hours of his Concord, Massachusetts, base. But as he continued to amass vintage greenhouse remains, he concluded that what now amounts to some 100 tons of old cypress roof bars, cast-iron vent wheels, and galvanized supports will move faster if he travels farther and teaches his skills to local contractors.

People with moderate talent can repair old greenhouses, Ward says. Most structures are modular, similar to Erector sets, and so can be reborn smaller. New Jersey client Susan Shaw, for instance, paid $1,500 for pieces of a greenhouse originally 24′ by 56′ and Ward rebuilt it as a more manageable 12′ by 40′.

Greenhouses are more straightforward than old houses, where problems are often hidden behind plaster and molding. “It takes a certain logic,” Ward says, “but it’s mostly assembly work, cleaning and scraping, getting steel sandblasted and galvanized. Vents may be decayed and need to be taken apart and re-glued. The job is probably closer to finish carpentry than anything else.”

Factors to Consider

If you want a solarium—an attached sunroom where you will relax and grow a handful of plants—decisions are relatively clear-cut, since the materials involved will be familiar to most builders. Depending on how much glass they have they can overheat, so you may want skylights you can open. Remember that when it’s cloudy you need to crank up the heat, says Jim Smith.

A greenhouse for growing a lot of plants brings up other issues, whether you’re buying or rebuilding:

Glazing with a lime-and-water mix prevents the restored Hearst greenhouse from overheating in summer.

Heat: Hot water systems in old greenhouses produce efficient, even heat, but can’t always be repaired easily. Smith says passive radiant heat is a close second choice. Ward’s client Susan Shaw says her attached greenhouse is warmed sufficiently by a heated pool and her home’s heating system. Another client, Brian Hollen, finds that his south-facing greenhouse helps heat his home, despite its location on a windy hilltop.

Ventilation: Greenhouses need a way for heat and humidity to escape. Vents can be as low-tech as simply opening windows, or be set to open and shut automatically via a computerized system that responds to temperature, wind, and rain.

Glass: For safety, greenhouse restorers usually replace old greenhouse glass with tempered glass, especially overhead. Ward says that, depending on the manufacturer, tempered glass can be wavy like old glass, with kind of a funhouse effect. Experts don’t always agree on whether the glass should be single- or double-glazed. Ward says it depends on whether you’ll be growing temperate or tropical plants.

Shade: In southern locations and depending on the structure’s orientation, glass is sometimes tinted or whitewashed all or part of the year. Shadecloth is another alternative. Tall plants can help shade smaller ones.

Supports: Museum houses usually replace the original material. At Hearst Castle, epoxy and reshaping allowed a restoration crew to rescue about 95 percent of one greenhouse’s original wood supports. It would have been easier to mill new pieces, says project leader Bruce Jackson. A homeowner would be hard pressed to put that much time and money into it.

Rusty cast-iron supports can be cleaned and galvanized. If any are missing, you can sometimes find original drawings and have parts recast. The New York Botanical Garden has a wealth of Lord & Burnham plans, as does Under Glass in Lake Katrine, New York, which took over the manufacture of that company’s greenhouses. An aluminum extrusion is a less expensive alternative.

Among suppliers of greenhouses and conservatories, many are distributors of structures designed and built in England. Says Smith, “They’ve been doing this for 200 years, and we’ve spent just the last 20 trying to catch up.”

With the recent flurry of high-visibility restorations and increased sales, however, he believes glasshouses may be on the cusp of a huge renaissance. He notes that Lord & Burnham built its famous Irvington, New York, foundry in 1895. “We’ve passed the hundred year mark. I think we’re going through a second wave.”