Colonial houses are easy to identify: They have a defined time period, and feature a specific set of architectural details. Colonial gardens, on the other hand, are a bit harder to pin down, as they cover a range of styles, attitudes, and design choices.

Running from each region of the country’s first settlement until the mid-19th century, they cover a broad range of patterns, ethnic traditions, regional variations, and personal styles, which explains why, say, a Spanish colonial garden in San Antonio feels very different from its New England counterpart. Confusing matters further is the fact that the true colonial era is often jumbled with the ideals of the Colonial Revival, the 20th century’s romantic interpretation of our early history. So what is a colonial garden? How can we define its character and capture it to create an appropriate setting for an early home? A look at some of the elements of original colonial gardens can help shape period-appropriate garden designs.

Dissecting the Colonial Garden

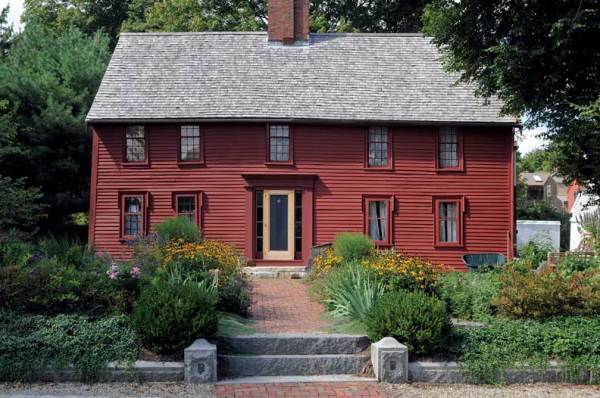

The slight setback of most Colonial homes presents a challenge in garden design, but bright perennials make the most of this space.

Despite regional variations, all colonial yards and gardens share some similarities. They are generally small spaces with carefully defined edges that delineate personal space from public sidewalks or an adjacent neighbor. They can seem cluttered and can be easily overloaded. By necessity, they often include the pretty and the practical: Walks and flowers surround mailboxes and trash containers. They are as organic and vernacular as the buildings they surround. They almost never have straight corners or perfect symmetry. Built in an era when time, money, plant availability, and even water were in short supply, they boast practical layouts dressed with the prettiest native plants and the hardiest plants from friends and family far away. Centuries of change have contributed to their unique character, as later design trends were infused into original gardens.

The design of original colonial gardens was heavily influenced by the restrictive size typical of colonial-era lots. Along the narrow, crooked streets of America’s villages, early Colonial houses huddled shoulder to shoulder behind tiny front yards. These village properties were designed to give owners equal access to the riverfront, water source, roadside, or village center. Most lots were barely 40′ or 50′ wide, with little room for a horse to pass between buildings into the rear yard. Behind the houses, long, narrow spaces offered room for work yards, gardens, and sometimes a stable or barn, accessible from a narrow side drive, a rear alley, or from the next road. Double lots offered more flexibility—if one could afford them.

Plants for the garden were chosen to guarantee bursts of color throughout the seasons, such as the hyssop that takes center stage in late summer.

In the country, where space was more plentiful, larger acreage and deeper yards offered more opportunity for gardens, though the never-ending work of the farm or ranch offered little time for pleasure. In the village, garden borders guarded against encroachment from the public or neighbors, whereas in the country, they kept out wandering livestock or errant chickens or geese. Paths were simple and direct, made of gravel or swept dirt, and covered with planks laid side by side on the surface of the ground for rainy or snowy seasons. Bricks, cobblestones, shells, bark, and other regional paving materials dressed up walks when they became available in surplus quantities. When times were good, or if homeowners were passionate about their gardens and had the room, an expanse of vegetables or herbs, or an overflow of pretty natives or hardy flowering plants, spilled over the dooryard, creating an exuberant seasonal display bordered by a hedge or fence.

Sometimes, outdoor areas were carefully intertwined with the uses of their adjacent interior spaces—kitchen yards related to kitchen activities, nicer spaces sat next to parlors or sitting rooms, and yards for outdoor work activities were located behind houses and near barns. For most, the manicured gardens we’ve come to associate with the colonial era were not a reality. Instead, most colonial gardens were everyday spaces filled with simple practicality, growing at the whim of available water and good weather.

Merging Past and Present

The new plan for the front yard flanks the brick walkway with a thick and constantly changing flower border.

How, in the modern era of decks, swing sets, patios, and multiple automobiles, can we create a yard that is respectful of a house’s colonial heritage yet seasoned with our own gardening interests and daily needs?

Small, urban colonial yards offer significant challenges in terms of space and privacy. Sometimes an entire yard is located at the front of the house, making it particularly difficult to gain privacy while still offering a welcome approach from the street. In the country, definition is necessary to create intimate spaces that feel more comfortable than open, windswept fields. Restoring the definition of the yard recaptures the scale and rhythm of its vernacular setting.

In one Ipswich, Massachusetts, garden, for instance, homeowners Ed and Barbara Emberly called on me to help tame the tangle of the past into a manageable, usable space. Less than 50′ separated the facade of their 1690 house from the road fronting the Ipswich River. The site had kept its 18th-century scale: The long, narrow lot, the small spaces on each side of the central garden path, the irregular bends in the driveway, and the rambling house (added onto over several generations) were typical of early New England villages. The contents of the garden had changed to reflect the planting fashions of three centuries.

Though charming, the site presented its own list of problems. Difficult grades coupled with dense clay soils created significant drainage problems, exacerbated by a three-century buildup of composted soils. Some of the existing trees were teetering on the threshold of mortality. The wooden stoop, a 20th-century addition, needed to be rebuilt, and the driveway, constricted by a cut-away in the hillside, was too narrow. The brick path that bisected the garden was misaligned, and the granite curbs and Victorian stone posts, added in the 19th century, didn’t fit the period of the house.

Homeowner Ed Emberly admires the just-blooming boltonia along the garden’s central path.

After I had inventoried and measured the existing garden, I drafted designs that fit both the period of the house and the couple’s personal desires. (As children’s book authors, color, texture, and special codas within the garden were important to Ed and Barbara.) Although “weedy” species were common in colonial gardens, the couple wanted to stay away from these invasive plants in favor of hardy indigenous species for their period-inspired design.

We removed one birch tree of questionable health, creating better site drainage along the driveway, but a large linden tree was simply pruned to accentuate views of the river. To widen the driveway, we cut into the hillside and planted the reshaped slope with lilacs, bearberry (a native groundcover), and daylilies. We lowered and reshaped grades to drain water away from the house. We also added compost everywhere to lighten the heavy clay soils, then we laid new walks using the old brick. We kept brick for the walkways because the Emberlys found the old brick walkway easy to shovel and more dependable footing than dirt or gravel. In the end, Ed and Barbara decided to keep the incongruous Victorian curb and stone posts as an acknowledgement that this house, too, experienced the 19th century, but they did replace the stoop with large fieldstones.

The new plan called for two open seating areas flanked by thick flower borders along the central walk and within a low sweetspire hedge (a less formal, indigenous alternative to box) planted along the street. Both the hedge and the rise in grade conferred a little more privacy on the garden. Instead of lawn, the space around the seating areas was planted with a carpet of myrtle (Vinca minor), another tough indigenous groundcover. The larger of the two seating areas was paved with brick, while the more intimate river overlook, on the other side of the garden, features granite fieldstone planted with thyme and pearlwort. The two areas weren’t meant to be symmetrical or complementary to each other; instead, I designed them for their practicality of place and space. The informal siting of the seating areas and the juxtaposition of different paving materials adds to the quirky vernacular character of the house and its setting.

Victorian stone posts, which were a 19th-century addition to the garden, were kept intact.

In bloom from early spring to late fall, the garden is ever-changing. In spring, sulfur-yellow basket-of-gold and waldsteinia, baby-blue forget-me-nots, white candytuft, and a range of tulips and daffodils wake up the garden. In summer, daisies, iris, peonies, roses, yarrow, and daylilies fill the garden with color, while blue cranesbill geraniums tumble through the borders. White and purple thyme, chives, and salvia reflect the blue and purple moods of the river. In autumn, black-eyed Susans, asters, late phlox, hyssop, and boltonia entice migrating butterflies to stop and visit amidst the changing fall foliage. Most of the plants’ genus dates to the early 18th century, though in some cases a cultivar was selected in favor of a longer bloom season or better resistance to pests and diseases.

Shaped by time, artistry, personalities, and the weather, this colonial garden has become home to another generation. For some owners of early homes, a faithful period garden might be the best choice. For others, careful research can offer insight into the regional vernacular character of colonial gardens and provide unlimited inspiration for period design. For all, the best colonial gardens celebrate the individuality of the site, the owners, and the region. Perfection often takes second place to practicality. The struggle to work within small spaces, irregular alignments, and the quirky twists of time offer the best opportunities to capture the spirit and the personality of the colonial garden and tame it for another generation.

Landscape designer and preservationistLucinda Brockwayis the author of Gardens of the New Republic.

Online exclusive: Find heirloom plants for your period garden in our nursery directory.