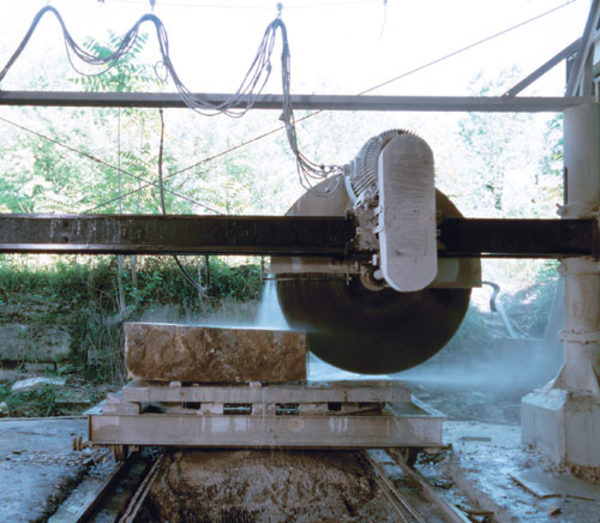

A 76″ diamond circular saw slices through a block of Texas limestone.

Memphis is justly famous for the blues, Beale Street, and barbecue, but this funky city overlooking the muddy Mississippi has another, unsung claim to fame—architectural cut stone.

From Renaissance Revival mansions to Arts & Crafts bungalows, hand-tooled veneers, classical columns, and carved moldings adorn thousands of city buildings great and small. That such a wealth of fine cut stone exists so far from the Indiana limestone belt is largely the legacy of one company—Christie Cut Stone, established here in 1906.

Architectural cut stone is stone designed and cut or carved to precise specifications, usually on a machine such as a lathe or planer. As one of perhaps a dozen full-service stone-carving mills in the United States, Christie fabricates all kinds of architectural stone, from simple bull-nose edgings to complex moldings cut from one piece of stone. The vast majority of the cut stone Christie produces is decorative rather than structural. Although the mill’s workers have been using pneumatic tools since the 1920s, Christie has yet to see the need for a computerized saw.

Working on a horizontal lathe, Dean Littleton transforms a rectangular blank of Texas limestone into a round cylinder.

“Our mill is designed for trim work rather than a lot of repetitions,” says Bond Christie, the third generation in his family to own and operate the mill. “The profile of the material we produce changes constantly, even on the same job. That would be difficult to do with an automated machine.”

While most of the orders for new and restoration construction Christie receives begin with an architect’s vision, custom work is rarely so precise. “Architectural drawings at a scale of 1/4 or 1/8 to 1′ usually aren’t drawn with enough detail for our needs, so we make our own shop drawings for each job,” Christie says. “They’re done on a CAD (computer-aided drafting) system.”

Once the shop drawings are ready, they’re sent to the architect and homeowner for review and approval. Then the shop creates drawings for each discrete piece to be cut. “We detail every piece in the jigsaw puzzle,” says Bill Linehan, who oversees Christie’s CAD operation.

Carver Stephen Wright wields a flat chisel to remove stone from the molding profile of a mantel.

From this, two full-size patterns are created. The first is a two-dimensional template in plastic, and the second is a three-dimensional profile in stone, typically about an inch or so thick. The stone cutters use these forms to create or modify the cutting tools they’ll need to carve the piece to exact specifications.

Once the work is in queue, Christie orders the specified stone in slabs or blocks, and has it delivered to the stoneyard. As an outcome of the methodical flow of the work, pieces for each job are usually cut in the order they’ll be assembled on the job site. “You can almost see the building emerge out of the mill from the ground up,” Christie says.

Behind a cut-stone facade with a tiny Doric portico, the shop floor at Christie is a noisy place. Its unwalled north end opens to a derelict rail yard. The spur hasn’t been used for 40 years, Christie says; raw stone and finished goods are trucked in and out by tractor trailer. The whine of direct- and belt-driven lathes and planers all but drowns out the buzz of pneumatic tools at the cutting and carving stations near the front of the building. When the shop is in full operation, conversation is impossible.

Ralph Littleton sets up the flat-bed planer for a run of cornice. He’ll be creating a coved molding profile on a blank that has already been sawn on the diagonal. In a stone mill, the planers are capable of three-dimensional cuts. Most everything has to go through a planer before it goes to any other station in the mill, Linehan says. That’s where we put the initial detail work on the stone.

On the first pass, a spray of debris flies off the blade. With each succeeding pass, Littleton makes slight adjustments to the position of the blade. Gradually, the crisp profile of the molding emerges. A few more runs, and Littleton’s job is complete.

Workers lay out the carved mantel on the shop floor.

At the open end of the shop, Mike Dinwiddie is working the 76 circular saw. Water streams over the diamond blade as Dinwiddie cuts 4′ x 8′ slabs from a 5-ton block of Texas limestone. Roughly 6 thick, these slabs will be cut down further, some to become blanks for the balusters Ralph’s brother, Dean, will turn on another lathe elsewhere in the mill.

Working with such large pieces of stone would be impossible without the four overhead cranes that run the length of the shop. (The smallest can lift 3 tons; the largest, 10 tons.) Soft, heavy canvas belts dangle from the crane to within a few inches of the limestone slab. Mike presses buttons on a control pad hanging at hand level to position the belts. He and a workman gently slip them over the ends of the slab on the sawbed. Antonio, the crane operator, lifts and hoists the stone to other waiting hands.

“The cost of cut stone doesn’t come so much from the material itself,” Christie says, but from the value added from cutting and carving. For instance, the shop might pay $8 per cubic foot for a large piece of Texas limestone—or about $575 for the chunk Dinwiddie now has on the big saw. Once it’s cut into slabs, it’s worth about $20 per cubic foot.

Robert Moses and Rick Tulles fit a cornice block on site and anchor it in place; a stonemason will tuck-point it with mortar.

“By the time it goes through the fabrication process, it’s up to $95 to $110 per cubic foot, depending on what we’ve done to it,” Christie says.

Add fine carving, and the sky’s the limit. Unlike many skills these days, stone cutting is a trade that requires the patience and precision of a craftsman. A good cutter must have the ability to match a profile not only for the length of a given piece, but so consistently that it matches the same profile on the next piece as seamlessly as possible. In most cases, it will take a worker four or five years to reach that point. The learning curve for stone carvers is higher still.

To folks who appreciate what cut stone means to fine architecture, the price is worth it. “You can build a nice house or impressive building without a single piece of limestone,” Christie says. “When people come to see me, half my job is already done. They wouldn’t be here if they didn’t want cut stone.”