If you have an old house, its first driveway was designed for a sedan tomotor to a one-bay garage. Adding a new driveway that will accommodate SUVs and a three-car garage might create an eyesore or drainage problem. When designing, consider some of the traditional ways the driveway was made to fit in. Curbs and borders mitigate an expanse of asphalt or concrete, as does a grass median. You might choose instead a surface of pavers, cobblestones, or pea gravel.

Take a walk around your city or town and you’ll see what’s traditional for driveways. No surprises: gravel and pea stone, outdoor paving brick, various stone types, and concrete are evident across the country, if not as ubiquitous as asphalt. Regional preferences apply: granite cobbles where they were quarried or shipped, brick in the South and anywhere rich in clay. In the past, you might have found crushed oyster shells or cinders.

You can mitigate the impact of a large driveway in choosing its location and by screening it with large shrubbery or trees. Creating a grass strip down the center makes it less intrusive, while lawns and planted borders will blur the edges.

If concrete and asphalt are deemed inappropriate, consider a driveway of pea stone (small-size gravel), finished at the street end with cobbles or outdoor brick. The whole thing will drain well, and winter’s city snowplows won’t tear up the street end. (Raking and replacement of the gravel can be a pain, though. You can get a similar look, if not the pleasing crunch beneath the tires, by using a treatment called chip seal or tar and chip, which involves embedding the stone aggregate into asphalt.) Brick and stone can be beautiful. Be sure you or your mason follows regional guidelines for depth and drainage to avoid frost heaving.

By the bungalow era, which coincided with the start of the automobile age, off-street driveways and back alleys were standard. Concrete was the most common paving for these driveways, and asphalt soon followed. Today, concrete has become an art form; artisan installers can color it, give it texture, or stamp it to look like slate or pavers. You can find precedent for almost any kind of paving. Your choice will depend in part on the length of the driveway, materials and colors already evident on the exterior of your house, and materials popularly used in your region.

Of course, design should include practical matters, not only aesthetics. Consider slope and drainage. Take heed of your weather, as snow and ice affect performance and longevity. Think ahead to long-term maintenance headaches and costs: brick units may be replaced, whereas concrete and asphalt usually need a full redo. Do you want an ADA-compliant design? Wheelchairs won’t move easily across cobbles. From the beginning of design, plan for lighting and perhaps even buried, low-voltage mats or cables to keep the driveway from icing up in cold weather with precipitation.

Cues From House Style

In-town or rural? New England or Arizona? Besides region and location, the style of the house suggests whether the paving material should be clay, stone, concrete, or even tile.

Formal Vs. Informal

Formality is often a result of design rather than the paving material chosen. Strong symmetry, clean edges, wide borders, and landscaped circles lend formality even when finished in gravel.

Location isn’t necessarily an indicator, as a country house may have a very formal driveway and motor court. Shingle Style houses and Arts & Crafts bungalows beg for a studied informality—through the use of pea gravel, old brick pavers, and soft edges—even if the overall design is rigorous. Mixing materials can lend formality, as with a driveway edged in bricks or several courses of cobbles. Or mixed materials may look storybook, perhaps incorporating tile or river rocks.

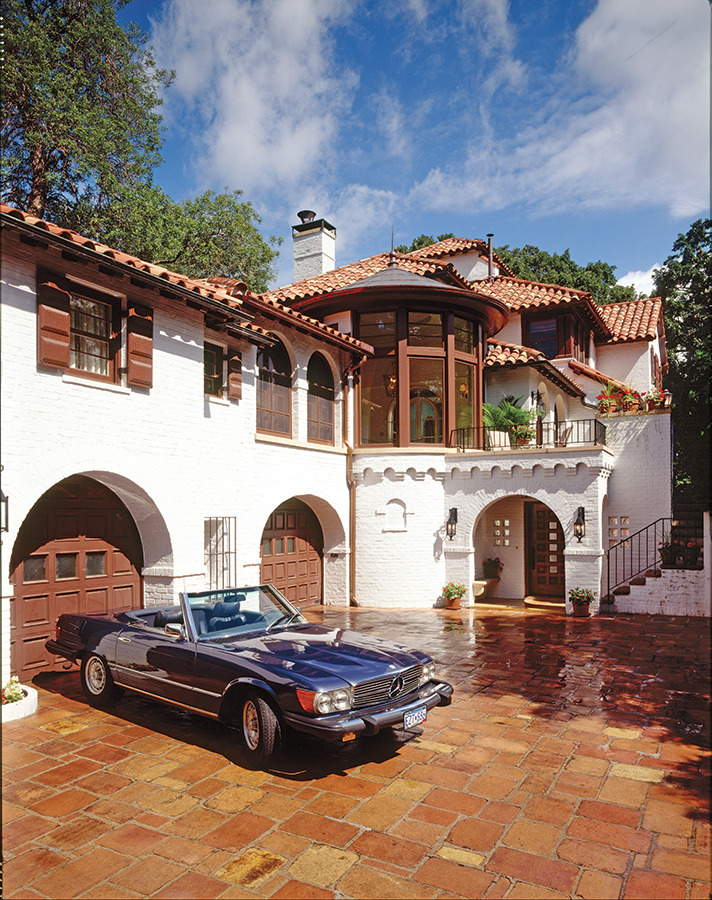

The Motor Court

For an authentic look, the driveway should be narrow close to the street. Further back, however, it may terminate in a smooth, paved area meant for parking or turning the car around. In the 19th century, when circular drives began to be added in front of fancier houses, they were neatly trimmed with a curb of cobblestones, cut stone, or brick. Then as now, the preferred paving material was gravel, or in some cases stone or brick.

Still, asphalt makes a good surface for a motor court. It looks more appropriate if used in conjunction with sections or borders of brick or cobblestone. Colored or textured concrete is another option for these large areas.

For both driveways and motor courts, brick pavers are classic and low-maintenance, if expensive at the outset. The laying pattern can be used to break down the scale of the space. To reduce runoff, today’s permeable paver options should be considered for large expanses of pavement. Concrete types hold up better than plastic grids under vehicle traffic.

Double-track Driveways

Dating to the early automobile era, this concept is applicable to houses built ca. 1900 to 1940 and for earlier homes that probably got their first driveways during those decades. Twin tire tracks of concrete, brick, or stone surround a grass (or moss) median, which diminishes the apparent width of the driveway.

The permeable center and verges allow rainwater to percolate: environmentally sound, it also helps avoid pooling and icing. With less paving material, the installation cost is probably less, as well. You do have to maintain the grass.

Resources

concrete stains

Kemiko

kemiko.com

paving brick

Old Carolina Brick Co.

handmadebrick.com

Hand-molded brick pavers

Pine Hall Brick

pinehallbrick.com

Durable pavers for walks & drives

designers

David Heide Design Studio,St. Paul, MN

dhdstudio.com

Frank Shirley Architects,Cambridge, MA

frankshirleyarchitects.com

Green II Builders, Altadena, CA

(626) 824-7120

Ground One Landscape Design, Bloomington, MN

GroundOneMN.com

Patrick Ahearn Architect, Boston, MA

patrickahearn.com