Double-hungs with a Queen Anne top sash are the highlight of this turret room. (Photo: Courtesy of Marvin)

Today’s modern skylines dotted with shimmering towers of glass make windows seem like nothing more than visual voids on a façade. However, windows are actually a vital element in the overall look and architectural character of any building, especially old houses. Try envisioning the long, horizontal louvers of a jalousie window on a Federal home instead of delicate, multi-paned, double-hung sash. It doesn’t work, does it? The right style of window on a historic home can make or break the exterior. And beyond appearance, of course, windows also provide light, fresh air, and a connection to the outdoors.

Materials for windows weren’t always so readily available. Glass in the New World was mostly imported from England and very costly. Crown glass, one of the earliest types of glass available, had existed for centuries, but only started being made in England in the late 17th century and later trickled down to the colonies. It was created by spinning a bubble of molten glass until it was flat, a technique that resulted in a bull’s eye (or “crown”).

Colonial windows were typically casements—sash that rotated out on hinges—and often were paired with wood or brick mullions separating the sashes. The frames were made of either wood or iron, and featured diamond-shaped leaded panes or rectangular ones. Given the expense of glass, windows were kept small. Muntins were thick (at least an inch wide), giving colonial windows a solid presence.

Double-hung twelve-over-twelve windows are a hallmark of Georgian houses. (Photo: James C. Massey)

In the 17th century, a new window development arrived: vertical sliding sash. The earliest versions were single-hung: the top sash fixed and the bottom moveable via pins and holes in the frame. By the end of that century, double-hung sash windows became the dominant style; they continue to be popular today. Double-hungs consist of two moveable sashes with a system of pulleys, cords, and weights inside the jamb that helps open and close them. There were also triple- and quadruple-hung windows (bearing three and four sash) that allowed for floor-to-ceiling ventilation, but these were less common.

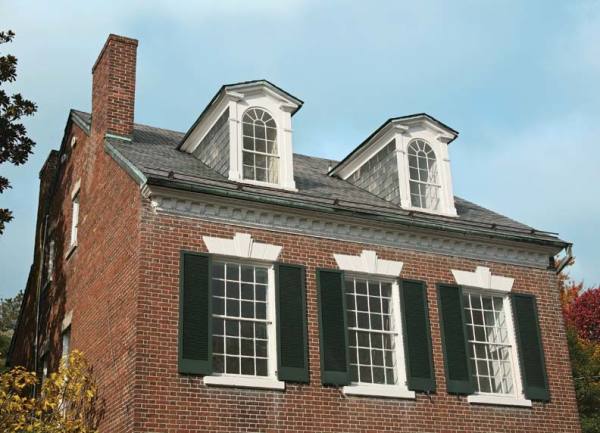

Georgian style homes featured double-hung windows with either twelve-over-twelve or nine-over-nine sash and muntins with a fairly thick profile. Glass was becoming more available, so the size of panes increased. Sash window openings were larger, brightening up interiors. As the Federal style came into vogue, muntins developed a thinner profile, and their depth was increased. These narrow muntins, combined with the larger panes of six-over-six sash, created more delicate-looking windows.

In 1825, the cylinder process for glass was invented. Glass blown into a cylinder was then split, reheated, and rolled into a flat sheet, allowing for larger panes of glass. Glass sheets for windowpanes became more uniform in thickness, although they retained charming hand-blown inconsistencies. A further development was the plate glass technique created by the French in 1850, which resulted in panes with a greater clarity. Originally developed for mirrors, hot glass was cast on a round or square plate, cooled, and then polished.

New technology allowed for expansive panes of glass by the Victorian era, like these arch-top reproductions from Marvin.

Over the course of the 19th century, house styles—from Greek Revival through Queen Anne and beyond—benefited from these improvements as window panes shifted from six-over-six to a single pane in each sash. The lack of muntins significantly changed not only how windows looked on the house, but also the view from the interior, which became less obstructed.

Another 19th-century development—scroll saw technology—meant that window openings were able to take on new shapes and decorative features. Both the ogee-shaped windows on Gothic homes and the rounded arches of Italianate houses embodied the new ornamental possibilities for windows.

Entering the 20th century, Arts & Crafts houses kept the popular double-hung windows, sometimes with a multi-paned upper sash, as well as casement windows. But the elaborate trim of the previous house styles was gone in favor of flat woodwork that was more in keeping with the developing aesthetic for simplicity.

During all this time, wood had dominated as the most affordable and easy-to-obtain material for window frames. But in 1890, manufacturers started making rolled steel for windows. It would take hold in the 20th century, touted for its fire-resistant qualities and cost-competitiveness.

Metal casements with rectangular or diamond leaded panes were popular on Tudor houses. (Photo: Todd Seekircher/Seekircher Steel Window Repair)

Rolled steel was made by passing the hot metal through smaller and smaller rollers. Although commonly used for apartment and commercial buildings, the streamlined look of metal windows also was a natural match for Art Deco, Moderne, and International style houses, where long spans of windows often punctuated the exteriors. Casements were the preferred type for residential windows, with multiple panes of rectangular glass—a style that became popular on romantic Tudor houses as well. Metal windows became such a competitive option during this period that wood windows mimicking their style were created, but with the advent of the aluminum window in the 1950s, they fell out of favor.

A final option in the evolution of windows was the jalousie window. With horizontal panes of glass set in a track that opened and closed them by a crank mechanism, jalousies were used on mid-century homes in areas with mild climates because they provided ventilation through the entire window; sometimes they are only found in certain rooms (think Florida rooms).

Windows—whatever their original variety—are more than just a means to allow light and fresh air into interiors—they’re an integral part of the architectural style of the houses they adorn. Next time, instead of looking through your window, take moment to look at it.