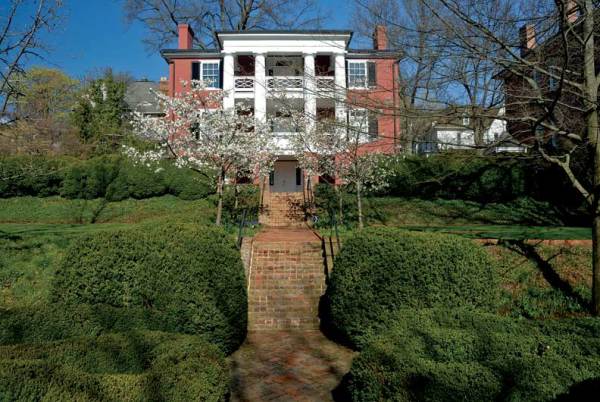

President Woodrow Wilson’s 1846 Greek Revival birthplace sits on a hill overlooking the town of Staunton, Virginia. A brick terrace, added in the 1960s by landscape architect Ralph Griswold, leads from the house down to the gardens.

Situated on the highest point of the historic Gospel Hill District in downtown Staunton, Virginia, the Greek Revival-style Presbyterian parsonage where President Woodrow Wilson was born was considered one of the finest houses in town when it was built in 1846.

Wilson was still an infant when his family moved to Augusta, Georgia, in 1858, but the Staunton house remained important to him. He returned in 1912, as the U.S. president-elect, to celebrate his 56th birthday, and upon Wilson’s death in 1924, his wife, Edith, worked actively with the trustees of Mary Baldwin College in Staunton to purchase the house and grounds for preservation.

Shortly after acquiring the house, the trustees focused on creating a garden for the property—one that would harmonize with the home’s era, and reflect the importance of its provenance. In 1932, the Garden Club of Virginia accepted the job of overseeing the garden’s creation, and hired Charles F. Gillette, a celebrated Richmond, Virginia-based landscape architect, to conceive the design.

Re-creating historic gardens can be tricky, as designers must balance capturing the essence of the old while meeting modern needs. It’s trickier still when few original documents exist. Journal entries from the home’s first resident indicated that there was a garden, but trustees could find no record of how it had looked. A strict following of historical conventions dictated a yard composed of outbuildings necessary for running the house, surrounded by a few functional plantings such as a vegetable garden. But the trustees of Mary Baldwin College didn’t want such a utilitarian garden for a home they intended to restore as a museum. Clearly, a compromise was required.

An aerial view of the grounds shows both the upper and lower terraces, and reveals the pattern of the boxwood bow-knot garden designed by Gillette in the 1930s.

Working closely with Edith Wilson, Gillette created a Victorian-inspired garden suitable to the 1846 construction date of the house. Today, 77 years after Gillette first laid out the garden, visitors can still see the core of his original design, which has been gently updated through the years. The formal garden is terraced into two primary spaces to accommodate the sloping terrain; the upper terrace near the house features a brick path that runs parallel to the house through a manicured lawn. Two summerhouses flank the house on this level, adding architectural interest.

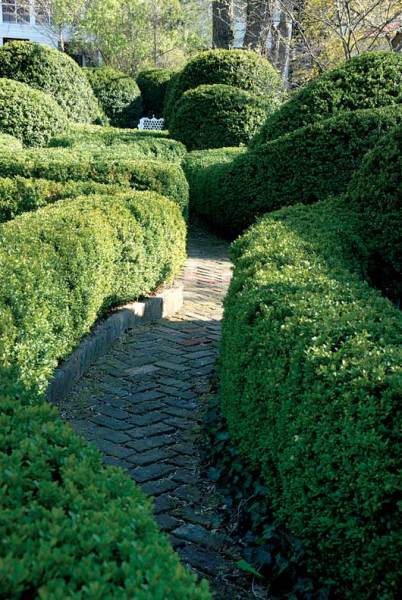

Herringbone brick paths wind through the bow-knot garden.

The lower terrace features boxwood-lined parterres planted in a fanciful bow-knot pattern. A brick path cuts a straight line toward the house, providing the sight-line axis from the house to the bottom of the garden, and bisecting the parterre garden on the lower terrace and the lawn on the upper level. On the upper terrace, this path is lined with white-flowering crabapple trees, which provide a froth of flowers in April and frame the view of the house throughout the year. Tucked beyond the parterre garden is a less formal space filled with white flowering shrubs, perennials, and bulbs.

In 1968, landscape architect Ralph E. Griswold was called in to add a brick terrace along the rear of the house. Paved in a herringbone pattern and edged with a low wall that opens to a central flight of brick stairs leading down to the upper garden level, this space provides a commanding vantage overlooking the landscape.

Practical Applications

Although classical gardens like the one at the Woodrow Wilson House are bigger than many homeowners have space for today, it’s possible to scale down key elements to fit smaller suburban lots. The secret is to know which features are typical of the period and to implement them in a way that is fitting to your own house.

For example, the large, elaborate boxwood bow-knot garden at the Wilson home could be scaled down into a parterre garden using small plants that lend themselves to close clipping, such as germander, rosemary, and lavender. If you fancy an allée, plant one, but use trees that fit comfortably on your lot.

Mingling tulips and daffodils line an allée in a quiet corner of the garden. From spring through fall, the garden blooms with annuals maintained by the Garden Club of Virginia.

There are even simpler steps you can take to introduce Victorian-era elements to your garden. Instead of acres of grass, a small lawn fits well with 19th-century sensibilities. By the late 1800s, the lawn mower had made lawn maintenance affordable, and having a grassy plot became the new status symbol. But these lawns were planted with intent, not as the default ground cover. They were an integral part of the overall design—a verdant canvas upon which to show off the principal decorations of the garden.

The Victorian age was the heyday of plant exploration as well. Exotic new plants were constantly being brought to the market, and people used these introductions prominently in their gardens. Often these plants would function as a piece of art: An outstanding specimen would be placed as a focal point, or an eye-catching exotic plant—such as a tall cordyline with a spray of spiky foliage atop a bare stalk—would become the centerpiece of an otherwise horizontal garden. Interesting foliage color or leaf shape, unusual growth habit, an arresting appearance, or pure novelty were all features cherished by Victorian gardeners. Considering the wealth of plants available to gardeners today, it shouldn’t be hard to locate that special jewel to put in a place of honor in your garden or on your patio.

The Woodrow Wilson garden has been called a 1930s Colonial Revival garden with Victorian accents. Whether strictly accurate to the period or a successful blend of elements from different eras, a well-designed garden with a sense of history is always a fitting complement to an old house.

Virginia-based writer and photographerCatriona Tudor Erleris the author of several landscaping and gardening books.