Stone walls help to define the new design.

Janice Parker’s botanic beginnings are evident in the care she’s taken to rescue and reuse more than 400 conifers on Turkey Hill Farm—once a 47-acre working Christmas tree farm. “I started as a horticulturist,” says the landscape architect at the helm of Janice Parker Landscape Design. “It’s a personal journey,” she says. “You have to work for years among plants to really understand them and use them correctly and effectively.” It’s this commitment to plant health care that is at the root of Turkey Hill Farm’s success.

Charmingly situated in the rural village of Millbrook, New York, the tree farm-turned-contemporary-homestead remains true to the property’s agrarian past. “It was very bleak,” says Parker of her initial impression of the property. “There was a sad story there. You could just feel it.” That may have been the case back in 2006 when Parker first set sight on what was to become one of the most challenging projects of her career, but today, it is teeming with life. And the Christmas trees still stand.

“[The homeowners] had stars in their eyes about what they wanted to do,” says Parker. They dreamed of vegetable and cutting gardens, grass-filled meadows, outdoor spaces for entertaining—including a terrace and a pool, an area for raising bees, fruit orchards, and a possible tennis court.

A solitary red barn defines the scope of the property.

With those things in mind, Parker formed a plan. It wasn’t to be an “arrogant, off-the-wall, arbitrary design” that didn’t make any sense for the property, she says. Rather than clear cut the land and begin anew, Parker gave life to the property’s historical context. “I felt this great sense of responsibility that there was all this agriculture there and many horticultural products on site,” she says. “We wanted to use those Christmas trees.”

During the site analysis, she and her team discovered an abandoned barn, a degraded second house that had once housed migrant workers, a hardwood nursery, a major water source used by area nurserymen, and an overgrown cemetery. Additionally, the 19th-century Greek Revival main house was in need of restoration. “I was really intrigued by the land,” says Parker. Civil engineering, soil science, horticulture, agronomy, and geology were major considerations, as was the historic significance and use of the land.

Parker included structural elements in the garden in the way of fencing, urns, walls, and fountains.

A series of irrigation canals was found running through the entire property. Marked by row after row of unkempt and crowded Douglas fir, blue spruce, and Norway spruce, the canals initially posed an obstacle, but were ultimately managed as a wetland. Existing white pines, large maples, locusts, and apple trees proved worthy and informed the overall design. Once trees deemed valuable were pruned back to health, Parker developed arcs and layouts that made both symmetrical and agricultural sense. “A farmer’s view of the land is never wrong; it’s actually quite beautiful,” she says. “They are growing the right plant in the right place in the right soil in the right orientation so things will grow and thrive. It was already in play there.” She, therefore, employed New England’s agricultural model of rowing things out.

Sourcing a small tree spade and a three-man crew, Parker set about rescuing, transplanting, and repurposing more than 480 conifers. As with most landscape designs, architecture, construction circulation, utilities, and geothermal wells presented challenges. But none were as looming as the Christmas tree crop. “Making sure the trees were protected and viable for the long term was part of the challenge,” says Parker. “It’s always a balancing act.” Moving the trees economically was also challenging. “I felt that it needed to cost significantly less to move them than to buy them,” she says.

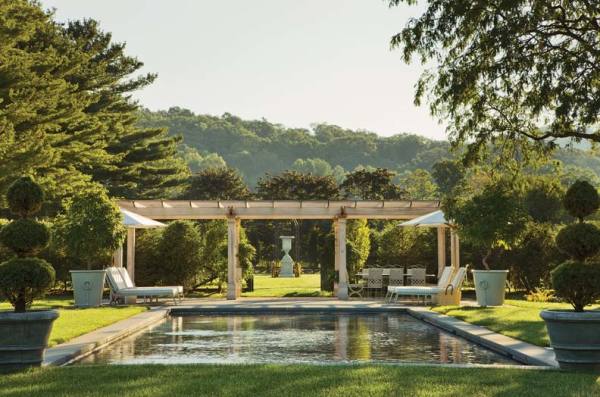

“We tried to keep everything connected,” says Parker of the resulting design. From the unfinished cedar pergola draped in wisteria that frames the pool area to the dining terrace edged in blue stone to the two hedged lawn rooms and line of ‘Miss Kim’ lilacs in front of the fruit orchard, Turkey Hill Farm is about connections. Row upon row of trees define the property, while elements like an iron trellis-topped urn planter centered in a room hemmed with cut fieldstone walls give it character.

Parker incorporated a pool complete with pergola and outdoor dining area.

Trick walls behind hedgerows and a second level of hedge in the center of one of the lawn rooms add mystery, while vegetable and cutting gardens form a strong center axis. “I think the overall surprise is when you walk into either one of the hedge rooms and find that pergola garden.” Large locust trees give presence to part of the pool area, and simple stone dust paths with grass joints lend the landscape a friendly, easy feel. “We got the effect of a really terrific design,” says Parker, “but we were able to use [on-site] natural resources. I thought it was a nice marriage.”

Parker and her team are still involved in the project today and visit the property regularly to keep abreast of its maintenance and long-term care. “Our eye has to be involved,” she says. “I don’t really have a choice. We have respect for what we have done.”

The design included vegetable and cutting gardens, as well as space to raise bees.

The first phase of the project took 14 months to complete, but there is much more to come. Last year, a garage replaced a derelict guesthouse, and granite spheres atop plinths were situated near the pool area for sculptural effect. Old stone slabs have since been salvaged and used to make stairs running between the two hedge rooms. Phases two and three will look more extensively at accessibility.

The homeowners are very hands-on and continue to develop the property. They use the place heavily and are revitalizing the ecosystem—they keep bees and have active birdhouses. “They continue to discover more and more things that they love about their garden,” says Parker. “To have clients [with] vision and to have those natural resources to work with just filled us with gratitude.”

Inspired by gardens belonging to the era between 1905 and 1920, Parker followed the example of landscape gardener Beatrix Farrand, author of Plant Book, which details her horticultural intentions and long-term maintenance regime for historic Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C. From its genesis, Parker included her preservation plans for Turkey Hill Farm. Initiated in 2006, it is now a well-established, dearly loved, and impeccably maintained property. “Go big or go home,” says Parker of its future development. “Whatever you do, do it.”