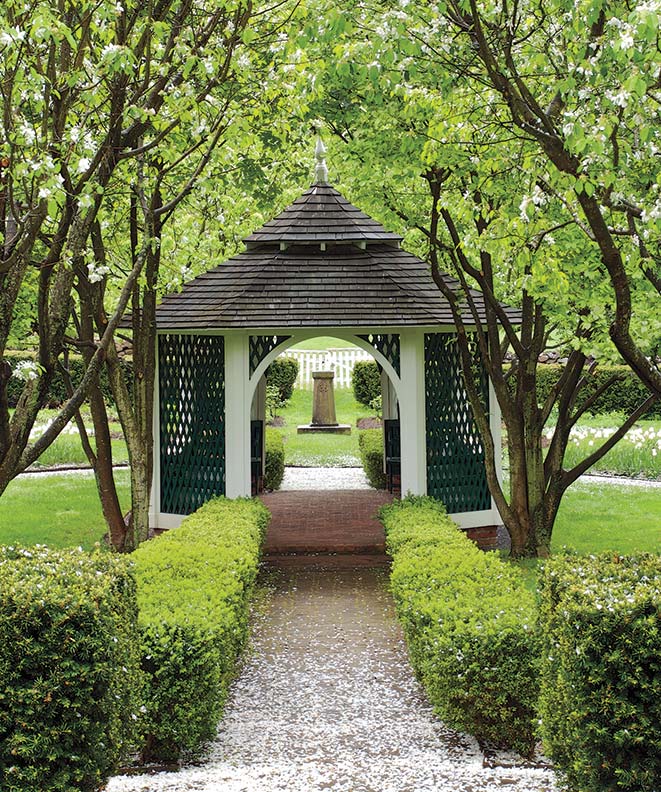

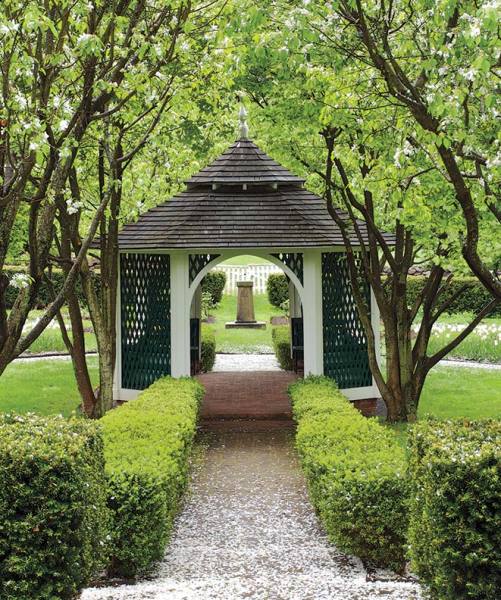

Boxwood outlines beds in a geometric arrangement featuring urns and statuary in this Colonial Revival Garden.

Jerry Pavia

Close your eyes and conjure an iconic image: birds splashing in their birdbath, sunbeams glinting off the armillary sphere, the scent of flowers, You have imagined a Colonial Revival garden.

Unabashedly romantic, nodding both toward formality and all that is lush…if this country could select an emblematic style, it would be Colonial Revival. Gardens in this mode span the centuries. No matter when your home was built, a Colonial Revival garden is apropos for an American house.

The Colonial Garden

The revival garden is, of course, a rosy version of history. The typical colonial landscape of the 18th century was nothing to be copied. Colonists were preoccupied with pushing back the wilderness, staking their claim, staying warm, and feeding the family. There was no time to fuss over flower gardens.

The period garden was a pragmatic affair devoted to vegetables and herbs, with a few unfussy flowers tucked in. Paths were beaten dirt; the layout marched to the door. A fence kept larger livestock from nibbling as they were herded to the town common for their daily grazing.

The Colonial Revival Garden

Gradually, the country was settled. As living became easier, gardens stepped away from pure agriculture, and Americans were influenced by European trends. Most historians date the Colonial Revival movement to the 1876 Centennial International Exhibit in Philadelphia. This World’s Fair was meant to publicize progress, but the 10 million people who attended to witness the telephone in use and watch engines spark went home, perhaps, with some unease. Technology had an unsettling effect. All those exotic plants in the Horticultural Hall, for example, had attendees taking a wistful look backward.

Many householders realized they didn’t really want tomorrow’s gardens, with strange plants newly introduced from the tropics; no, they wanted grandma’s garden. Given the introduction of labor-saving technologies and leisure, they had time to tend flowers. Everyone bought into a cleaned-up, rose-colored rendition of the past.

Lilacs in bloom in the Colonial Revival gardens at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont.

Gardens of the Colonial Revival gardens had frivolities—there was nothing Puritan about them. They featured sundials, birdbaths, fountains, and urns—all placed in a plan of axial symmetry. Paths were straightforward, the better to view focal points. Fences often delineated the space, but they might have a wrought iron gate with vines trained overhead.

Read more about Colonial Revival Gardens:

- Gardens of Colonial Virginia

- Colonial Revival Revealed

- Colonial & Colonial Revival Garden Design

- Early Colonial Revival Architecture

Alice Morse Earle Leads the Way

Author and historian Alice Morse Earle (1851–1911) is credited as a leading figure in the movement toward the Colonial Revival. She began her campaign paying homage to the past with numerous books on aspects of colonial life. By 1901, she’d turned her attention to the outdoor scene with Old Time Gardens, followed by Sun Dials & Roses of Yesterday in 1902.

Earle was a tastemaker particularly fundamental in selecting the sundial as the signature feature of the Colonial Revival-style garden.

At Colonial Revival Hill-Stead (1901) in Connecticut, the sundial is a focal point beyond the axial path that leads toward the summer house.

Sundials, Urns and More

John Endecott, the outspoken Puritan and governor of the Bay Colony, imported an early sundial in 1630. So the sundial was an authentic feature, with a utilitarian function settlers found essential.

Fountains, on the other hand, had not been prevalent in a country where getting water from place to place was a practical matter. As late as 1841, Andrew Jackson Downing mentioned that fountains were far from commonplace. So the 30′ cast iron fountain made for the 1876 Centennial Exposition by French sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi (creator of the Statue of Liberty) made a splash in America. Still, the Colonial Revival movement was more likely to embrace romantic cherubs and nymphs piped with water jets rather than the tazza bowl-above-bowl style of fountain popular in Europe.

More often, gardeners went with urns as focal points in their Colonial Revival gardens. Urns were receptacles for the tropical invasion; rather than planting tropical plants in beds, Americans tucked them safely into urns. Urns still offer a way to incorporate temporary plants—annuals—into the scene.

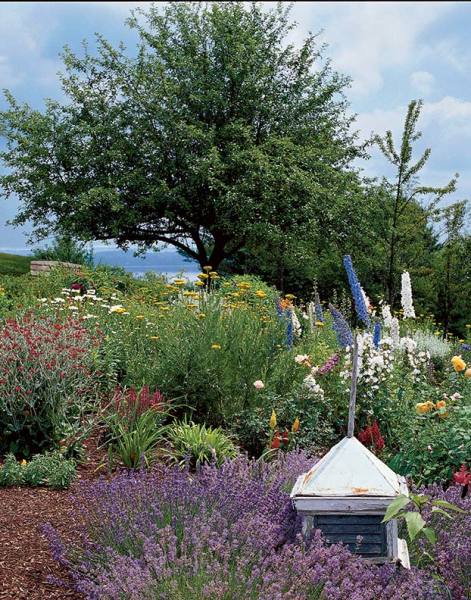

Delphiniums and phlox, daisies, foxgloves, lupines and roses are part of an old-fashioned garden surrounding a colonial-era house in coastal Maine.

Gross & Daley

Meanwhile, the layout of the Colonial Revival garden offered the perfect configuration for incorporating focal points. To give a proper view, paths were straight, generally paved with brick, and cut through geometric beds that held perennials. Corralled within edgings of clipped boxwood or privet (“clipped” was critical), plants were blowsy and floriferous.

With formal lines and plenty of fillers, the Colonial Revival garden was robust. Plants tumbled together in densely packed beds. If they transgressed upon the path and scented the sunshine, all the better. Birds and pollinators were part of the ambiance.

The Colonial Revival garden has all the qualities we still hold dear. With a heritage common to many styles and eras, a sundial and a brick walk flanked by geometric beds will always fit.