A Vermont couple took advantage of the abundance of stone on the land to rebuild a tumbledown rock garden and terrace, including broad steps that descend from a trellised patio, behind this Federal-era home.

Carolyn Bates

Physical Evidence Start by reading the landscape. Remnants of a stone wall, a row of bricks turned up by a rotor tiller, or an old outbuilding foundation half buried under leaves all may be indicators of historic walks, garden edging, or even the backyard privy. Don’t overlook the presence of stumps or vines; these may be clues to an original garden layout and some of the plant species within it. Plot any evidence you find on a rough site plan and see if it begins to make sense. Those old bricks may have been part of a path; layers of cinders or oyster shells are suggestive of walks or paths from the days long before mulch and stone dust were common. That huge old wisteria root may have come from a vine supported by a sturdy pergola in a sunny part of the backyard.

Evidence can be found just about anywhere— particularly in truly old landscapes. But that doesn’t mean there are no hidden features ready to be revived in the backyard of a house built just 75 years ago.

Photography Old photographs of a house reveal how the porch once looked, whether the windows have been changed, or the side door moved. But they can also point to the presence of old flowerbeds, long-gone fencing, gate posts, or auxiliary structures from pergolas and gazebos to early garages. Start your search in the local history section of the public library, where reference librarians will guide you to indexes of old photographs, postcards, and maps that show the locations of structures. If you know the names of previous owners, check online sites such as Ancestry.com. Someone may have posted photos of family members posed in the backyard or on the front porch of your house. Add any details to your sketch plan as they turn up.

Don’t overlook information gleaned from early aerial photography, available at your local tax office or online parcel viewer. Images as recent as 40 years ago may show the locations of now-missing sidewalks, drives, and sheds, which may lead to finds of physical remains. If your tax parcel viewer includes infrared photography, review shots of your lot carefully: infrared images may show the presence of objects not visible in normal photography.

Pro Tip: When a lost feature is found documented in an old photograph or rendering, use the document to mark the precise location and orientation to the surroundings.

The site plan for the semi-circular Lipkind House, designed in 1954 by architects Peter Berndtson and Cornelia Brierly, specified a carport, a central pool between yard and entry, and garden plantings. The current homeowners added planting beds edged with stone and brick to separate them from lawn.

William Wright

Magazines and Newspapers Early 20th-century magazines like House Beautiful, Country Life, House & Garden, and others regularly published photo spreads of architect- and builder-designed houses along with site plans. Newspapers often ran ads for new subdivisions and newly completed houses. While many of the featured homes were photographed soon after they were built—so they may lack hardscape elements added later—you might get lucky. If your home was ever featured in a magazine or newspaper, the local library may have a reference copy.

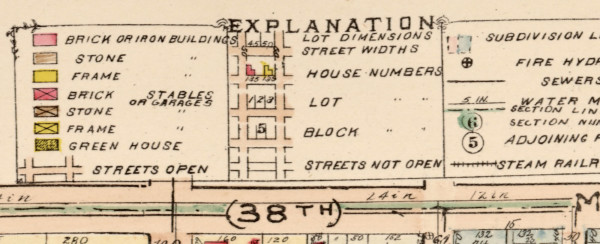

Maps Old-house owners have long relied on fire-insurance maps (known as Sanborn maps for the company that first began producing then in 1876) for help in dating a house. But these maps also indicate the outlines of all or most of the built structures on a parcel or lot, including carriage houses, garages, greenhouses, and wells. If you know the cross streets and parcel number of your property, it’s relatively easy to find your lot. Since the maps were used for insurance against fire, they also indicate whether the buildings are brick, wood, or another material. Most of the Sanborn maps were published between 1880 and 1920, peak building years throughout the United States. A large collection of Sanborn maps, including those for cities in 34 states, is available online at the Library of Congress. The Library also holds an extensive collection of detailed maps and aerial views of towns and cities published by other sources. Many show the same structural indicators as Sanborn maps. An index is searchable alphabetically, and Sanborn and other map images can be downloaded at high resolution at no charge.

Building and Site Plans If your home was designed by an architect or renowned local builder, you may be able to find building or site plans. Frank Lloyd Wright and other 20th-century architects often included landscape plans as part of the overall design for the house. (While some of the indicated features were built as designed, others were not. Especially with Wright houses, subsequent owners often faithfully added proposed hardscape elements, but at a later date.) For houses of historical significance, there may be plans for gardens or auxiliary structures. With luck, plans may be stashed in the attic, a seldom-used closet, or an old safe. Plans may also be recorded at the local tax office. If you do find plans that include landscaping, it’s a good bet that your historic landscape will begin to come to life, at least in your imagination.

In a present day photo, the pond is surrounded with lush plantings, weeping willows, and other ornamental trees. The owners not only dredged the pond, but they also added the moon bridge painted carnelian red.

Carolyn Bates

Landscaping the Past

Once you’ve amassed all the information you can, you may find the historic landscape emerging. Some tips:

• Think in three dimensions. While hardscapes can be flat like a brick path, they can also be three-dimensional structures like chicken coops.

• Extend out from the footprint. That same brick path may have once been the center of a gardenscape that stepped up in tiers of plantings, from low groundcover along the path’s edges through annuals like day lilies, and finishing with climbing roses or a tall ornamental hedge.

• Think above and below grade. A depression surrounded by lush overgrowth may once have been a pond edged with stone; stubborn old roots may suggest a stand of box hedges or crepe myrtle once grown high along a long-lost path; a concrete foundation may be all that’s left of a water tower or windmill that served the house.

• Interpret the existing landscape. If the flagstone patio behind a 200-year-old house drops off into a rubble-strewn ravine, for instance, it’s likely that a previous owner once built a terrace or steps there—or considered doing so.

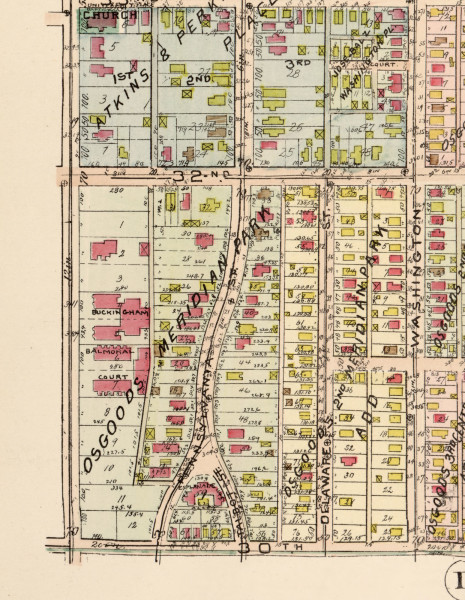

The key for the Meridian Park neighborhood map conveys information about lots as well as buildings and their construction.

Using Aerial Maps

A detail of a 1916 color-coded map of an early Indianapolis suburb shows the location of houses and auxiliary structures like garages.

Sanborn and other aerial maps are packed with information, providing you know how to read it. A detail from a 1916 map of Indianapolis’ historic Meridian Park neighborhood, taken from Baist’s Real Estate Atlas, clearly shows the location of houses and outbuildings, color-coded by construction material. While most houses are either masonry or wood-frame construction, the smaller buildings in backyards are almost universally frame structures. An X in the box indicates that they are stables or garages. It’s relatively easy to find and compare the area to the present day by zooming in on Google Maps. In this case, several outbuildings have disappeared. While a careful search on the ground might reveal evidence of an old foundation, the old map is so accurate it may be possible to reconstruct a “new-old” garage or shed from the footprint shown on the map.

An aerial photo from the mid-20th century confirms the locations of pond, gazebo, and other landscape elements in relation to the main farmhouse.

Case Study: Aerial Photography for Historic Hardscapes

An overgrown rock garden was all that was left of an extensive hardscape at this 1799 farm when the Andrea and Randy Brock bought it more than 30 years ago. Aided by aerial photography and pictures taken in the mid-20th century, the owners set about restoring hardscape that included a large pond and gazebo, and reviving the now lush gardens.

Among their discoveries on the land was half of an old millstone, once used as the first step in a walkway; they mounted it vertically on a stone block, converting it to an art piece honoring the history of the farm. Rebuilding the rock garden and adding terraces was an organic process. No need to look for rocks, says Andrea: “They came with the place.”

Re-created arbor.

Gross & Daley

Case Study: Archival Photos

In addition to re-creating the trellised arbor and gate, the owners had new striped awnings patterned after the ones that appear in a 1935 photo.

This transitional 1926 Colonial Revival house had a remarkably intact interior, but some of its hardscape details had been lost. The owners would never have known that, had they not inherited five photographs of the house and grounds taken by a professional photographer in 1935. The owners used the archival photos to re-create the trellised arbor over the front gate, matching details clearly shown in the photo.

Other photos of the backyard revealed an unusual waterfall—a sloping slide of rocks that directs rainwater into a small pool. Turns out the rock waterfall was still there underneath the foliage, as were an original garage and the path that leads to its double-bay doors.

Garden Site Plan

In Alice Longfellow’s restored Colonial Revival garden, a large arbor with bench seating looks across the formal garden toward the carriage house built in 1844.

Eric Roth

In 1844, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow planted a small formal garden “in the shape of a lyre” in the northeast corner of his Cambridge property, complete with plans. He later enlarged it after a design he had seen in Italy. Daughter Alice added a sundial at the garden’s center in 1903, along with a latticed pergola, and in 1904 hired Martha Brooke Hutcheson to revive the 1844 plan. After Alice died in 1928, the garden reverted to weeds and overgrowth.

In 2003, the National Park Service, which manages the property, began a re-creation of Alice’s Colonial Revival garden. The 1904 design followed Longfellow’s original invention, which was intended to mimic the pattern of a Persian carpet. At the center is a circular walk around four paisley-shaped planting beds. The center of the garden is flanked by long, rectangular pathways on either side; additional planting beds are squares turned on the diagonal. The large, elaborate pergola and a latticework bench were rebuilt, all according to early 20th-century plans.