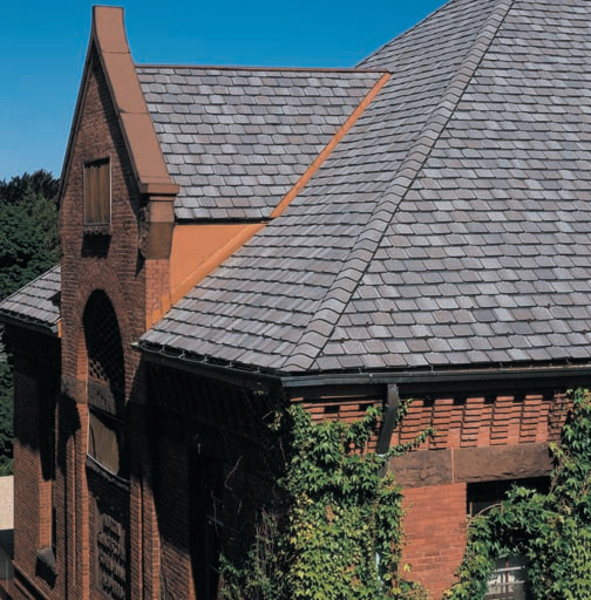

Deep shadows and shades of gray are the essence of slate roofs, and the appearance manufacturers emulate with asphalt shingles. Using multiple layers of laminated asphalt shingles in convincing slatelike shapes reinforces the impression. (Photo: Courtesy of Elk)

Long the pride of homeowners by virtue of its beauty, stability, and longevity, slate reached peak popularity as a roofing material around 1915. As early as 1906, though, manufacturers were already experimenting with man-made alternatives, such as asphalt shingles and asbestos-cement slates, that could be made lighter, cheaper, or easier to install. The search for the perfect slate substitute continues today. The choice of products grows wider every year, while the list of manufacturers changes annually as new players enter the market and old ones leave. Since modern slate substitutes may be one of the options for old-house owners replacing or extending a natural slate roof—or an ersatz slate installation from, say, the 1930s that is now historic in its own right—OHJ has put together the following buyer’s guide to help sort out the many products, materials, and makers that represent the state of the art in this evolving industry.

Simulated Slate Suitability

Natural slate is famously long-lived. Nonetheless, many old houses are at the point where their original slate roofs have reached the end of their useful lives. New slate is readily available, but it is expensive to buy, expensive to install and, as a natural piece of split stone, unforgiving of mistreatment. While the variety of man-made substitutes on the market includes some adequate to very good replicas of the real thing, these substitutes are just that—their shape, thickness, size, color, and longevity are not the same as the original material.

If you must reroof an old slated house, by all means do so in slate when possible. If enough of the slate is still in good condition (see Slate Weathering, May/June 2002 OHJ), consider removing it, repairing the underlying sheathing and flashing, then reusing the good original slates on the principal roofs—that is, the ones that show. You can then use new slate or a substitute on the rear or subordinate roofs.

The degrading effects of sunlight, as well as extremes of temperature and moisture, can take their toll on man-made slate as much as any building product. These fiber-cement slates, the modern alternative to the asbestos-cement products popular in the 1920s and ’30s, show some fading on an otherwise sound roof. (Photo: James C. Massey)

After a shaky start, simulated slates are finding growing acceptance for restoration projects because of better quality replicas and good performance on historic buildings in Europe (where they have been extensively used for several decades). Though these are still substitute materials as defined by the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, some of the better products have garnered cautious federal government endorsement for preservation use. Sharon Park, FAIA, senior historical architect for the National Park Service Technical Assistance Division, recommends checking with your local historical commission, if there is one, and with your State Historic Preservation Office concerning the appropriate substitute slate for your project. This is obligatory if you hope to cash in on tax credits for home rehabilitation in states that provide them.

Losing the character and patina of an old slate roof is always regrettable, but Park acknowledges that there are circumstances when a new or man-made roof becomes necessary. Regarding replacement materials in general, the National Park Service stresses that they be compatible with historic materials in appearance. As outlined in Preservation Brief number 16, The Use of Substitute Materials on Historic Building Exteriors, the new, substitute material should match the details and craftsmanship of the original, as well as the color, surface texture, surface reflectivity and finish of the original material. The closer an element is to the viewer, the more closely the material and craftsmanship must match the original.

Concrete tiles, with their thick butts and rich, textured surfaces, offer another way to obtain the picturesque character of architectural slate roofs. Installing colors in a random pattern enhances the effect. (Photo: Courtesy of Vande-Hey Raleigh)

Shopping for Slatelikes

How do you evaluate the appropriateness of a slate lookalike installation for your project—especially when it may be a material that is totally different than stone? As with any major expense, you should choose carefully, do some homework, and ask detailed questions. Here are some key considerations that may affect your eventual decision:

1. Look for compatibility with the old slate roof in size, color, finish, and installed appearance.

2. Evaluate the color permanence. Is the color applied to the surface or integral to the material? Some slate replicas have faded badly over time.

3. Follow the manufacturer’s installation specs carefully; each product is different. Don’t forget that you will still need good underlayment and flashing.

4. Be certain your selected product is compatible with your climate. Not all replicas serve well in very cold, windy, or otherwise stormy climates.

5. The installation on the valleys, peaks, and ridges should be the same as on the original roof. Most manufacturers make special shapes for these applications.

6. Consider the weight, which can exceed 1,000 pounds per square (a 10′ x 10′ area) and may require roof reinforcement.

7. Make sure the material is fire-rated.

8. Ask the supplier about expected longevity and any warranties the product might have.

The latest breeds of simulated slates come in several quite different materials, from the old standard concrete tiles to new ceramics and recycled rubber.

Fiber Cement: This is the oldest type of substitute slate (and also of wood shingles), dating in its original form to the first decade of the 20th century. Modern versions, made with non-asbestos cellulose or man-made fibers, have wide use on roofs, on mansard dormer cheeks, and as siding. Most fiber-cement slates bear close resemblance visually and physically to the real thing. Manufacturers may specify the use of storm anchors. A major consideration is that installation labor costs are roughly the same as with real slate, making the lower material cost the only savings.

Concrete Tiles: Concrete slates have been around for a long time but aren’t as well known as other materials. They employ basically the same binder (cement) as fiber-cement slates but leave out the fiber component. Instead, they are made like concrete, with aggregates (such as sand and perlite) and sometimes metal reinforcement. The resulting slate is thicker than fiber cement and very heavy—sometimes more than 1,000 pounds per square. For that reason, concrete often requires heavier than usual roof framing and is less than desirable for steep slopes. Concrete slates require special installation in areas subject to 125 mph winds.

Clay Tile: The most promising among the newer forms of roof tiles, slatelike and otherwise, clay tile is hard and strong, with integral color or glaze color. Much used in Europe, it is rapidly gaining ground in the United States. There are some color limitations, and the product does not have the irregular edges of true slate. The tiles are generally interlocking.

Another asphalt approach uses heavy base shingles and clever color placement to play up shadow lines and random butt lengths. (Photo: Courtesy of Certainteed)

Asphalt Shingles: The standard house roofing, made for a century in one formulation or another, asphalt shingles are affordable, efficient to install because they come in strips, and available in almost endless variety. In recent decades, the industry has moved into making what are called architectural or laminated shingles. These employ two or more layers of roofing material to produce a more textural effect with softer lines and deeper shadows. First popular in wood-toned shingles, these techniques have been turned to emulating the appearance if not the actual form of slate roofing, with appropriate colors and shadow lines. An added benefit of some of these products is that they are thicker and therefore longer lasting than the standard three-tab strip shingle of yore. Many companies now make asphalt slatelike shingles—none perfect imitations, but all relatively inexpensive and easy to install.

Recycled Rubber: The latest class of competitors in the slate lookalike market are composed of recycled rubber (from industrial waste to automobile tires) and polypropylene. Most are updated, slatelike versions of the time-tested asphalt shingle, following in the path of wood-toned architectural asphalt shingles. The materials are too new to comment on life span, but their light weight and slight flexibility are good news. Each product generally strives to look like slate, with realistic surface textures, chipped edges, and authentic colors. Compared to real slate, they are also relatively inexpensive. Manufacturers claim the roofing is good in high wind conditions.

Slate/Resin Composites: Another new and promising material, pioneered so far by just one manufacturer, is best called a composite slate. This product is an amalgam of likely components—ground slate, resin, and fiberglass—bonded under high pressure to form a realistic-looking slate substitute. The process produces good modeling of the irregularities of slate itself with integral color and typical unit sizes, paired with the appeal of light weight.

Examine several kinds of man-made slate to choose the best material and color for your use. You may decide that the slate look isn’t for you at all, in which case the firms that make slate reproductions also make wood-grain and various tile repros as well.