A painstakingly restored camellia garden surrounds Duffields, a 1920s house in South Carolina.

Flowering evergreen shrubs or small trees were idealized in Chinese and Japanese art and literature for centuries, but the first camellias only arrived in the United States in the late 1800s. In the early 20th century, interest in these flowers had reached a fevered pitch. While affluent landholders or botanical organizations were among the first to collect and cultivate camellias, some home gardeners also embraced the plant. In Camden, South Carolina, a restored small private garden known as Duffields boasts a remarkable collection of camellias, and an equally remarkable story.

Polly and Nick Lampshire purchased Duffields, a circa 1923 brick house, in 1992. At the time, the house was shrouded from view by overgrown shrubbery, large trees felled by Hurricane Hugo’s 1989 devastation, and invasive vines such as smilax, ivy, and wisteria. The real estate agent told the Lampshires that the house had once had an extensive camellia garden created by one woman, Helen Harman, who had owned the property from the 1930s to the late ’50s—but there was little hope that any of the plants had survived. The lost garden piqued the Lampshires’ interest. They purchased the property after falling in love with its well-proportioned eclectic revival house and original pierced brick garden walls, which peeked out from beneath the overgrowth.

The Lampshires began exposing those walls in early 1993. Polly was removing ivy from a wall near the back door when she spotted a bright carnelian bloom. “I was amazed to see it, and so excited that it might be one of Miss Harman’s flowers,” she says. It was indeed a camellia on what looked to be an old plant. In an effort to identify the flower, the couple contacted a well-known local garden designer and historian, Sallie B. D. Iselin.

The pierced brick garden walls—an unusual feature, pictured here behind the front garden’s central fountain—were also meticulously restored.

Ironically, Iselin and her husband had considered buying Duffields for their own young family, but the project seemed too much to take on. When the Lampshires hired her to help uncover the hidden garden, Iselin says she knew she was “meant to work in this garden in one way or another.” The Lampshires and Iselin spent the entire first year clearing and cutting back the overgrowth.

Clearing went quickly at first, but then complications arose. The more overgrowth they removed, the more camellias they discovered. Iselin soon realized that the overgrowth served a protective purpose: It prevented trees felled by Hugo from crushing the remaining camellias and provided much needed shade for the plants. She had to proceed thoughtfully. She also began to see a pattern emerge. “Most of the surviving plants were on the large, north-facing woody slope behind the house,” Iselin says.

Unraveling a Mystery

Duffields’ camellias bloom in an array of colors, shapes, and sizes, including Camellia japonica.

From the beginning, the team had been baffled by little bits of chicken wire sticking out of the ground on the property’s north-facing slope, but they soon had a breakthrough. Wherever they found wire they also found the telltale cinnamon bark of Camellia sasanqua. Because this plant is hardier and more disease-resistant than other camellia varieties, Iselin surmised that Harman used C. sasanqua stock for grafting her C. japonica plants, and that the chicken wire protected the plant roots from voracious moles. From this start, the team developed a system for unveiling the shrouded garden: They followed clues, discovered new surviving plants, and then exposed only the north and east sides of the plants. After the plant hardened off, or toughened to the elements, the south and west sides were also uncovered.

During the first two winters, Iselin spent a great deal of time platting, photographing, and labeling each newly discovered plant, but by the end of the second winter, with still far too many survivors to categorize, she resorted to marking the plants that were not to be disturbed with pink construction tape.

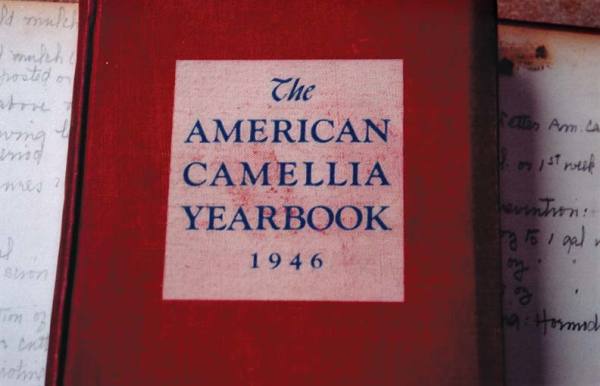

The Lampshires also began to renovate the house in 1993, and soon they came upon a small library of garden books, including many American Camellia Society Yearbooks. The front and end plates of the books were a treasure trove of information, where Harman had scribbled notes detailing everything from when she had purchased plants and propagated new flowers to her timetable for fertilizing, pruning, and watering her garden. The notes illuminated the extent of Harman’s expertise in the region, as well as her connections throughout the camellia world from Florida to California. They also helped identify some of the camellia species unearthed more than 50 years after they were first planted.

Detailed notes in the front and back pages of Helen Harman’s 1940s American Camellia Yearbooks proved invaluable to the restoration efforts.

To learn more about the garden, the Lampshires and Iselin researched historical archives and city records, and tracked down some of Harman’s contemporaries to speak to them. Those efforts, along with information uncovered in the garden itself, have revealed much about Harman and her secret garden. When she bought the house in 1937, she was a single woman from New Jersey and a long-time member of the Camden Garden Club, even serving as its president from 1947 to 1950.

“She was recognized as a camellia expert around South Carolina,” says John Lindsay, a local nurseryman who was just 20 when Harman began mentoring him and taught him the art of grafting. “She was meticulous, and had a beautiful eye for design,” Lindsay says, noting that Harman laid out all of the extensive plantings and paths throughout the property and maintained them herself with the help of just one other person. Lindsay recalls Harman gardening at all hours and maintaining a precise four-bin system of composting to keep potting materials separate from the lawn, camellia, and azalea cuttings. She drove all over the state to address gardening and horticultural groups, find new plants, and talk to other growers. “The sheer number of plants on Miss Harman’s property was astonishing,” Lindsay recalls.

In the backyard, blooming camellias pepper the landscape, creating a charming, colorful backdrop to the brick patio.

At a time when there were few women in horticulture, Harman was a self-taught authority on the subject. She was as generous at dispensing her knowledge as she was with distributing her plants, but then tragedy struck in 1959, when a fire destroyed much of her house. Harman managed to save her library of garden notes, but by late 1960 she had returned to the Northeast, where she later died.

Thanks to the Lampshires’ hard work, more than 100 Camellia japonica, Camellia sasanqua, and Camellia reticulata plants are growing again at Duffields once more. The pierced brick walls, previously held together only by the vines that obscured them, have been rebuilt. The terraced garden pathways have been restored, and the protective canopy of pines replanted. The garden is once again tended to meticulously.

From November through the beginning of April, when the flowers bloom, the Lampshire house is full of cut camellias arranged in vases or, more traditionally, only the blossoms floated in a bowl.