Cornerstones Community Partnership

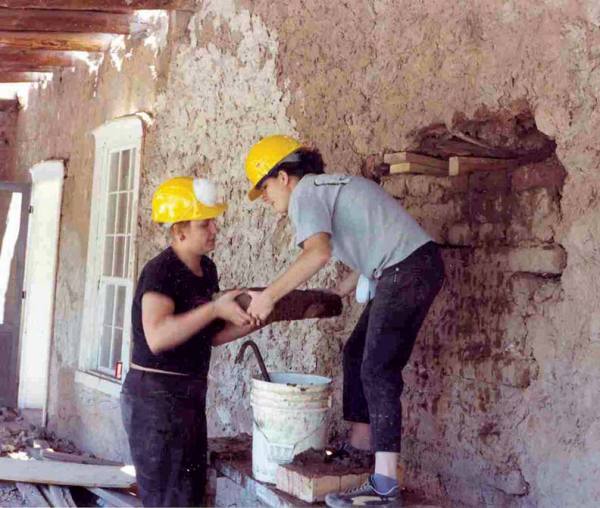

Volunteers from Youthworks help Cornerstones Community Partnerships restore the Gutierrez-Hubbell House, a 19th-century adobe hacienda.

In New Mexico, a state with a rich and far-reaching architectural heritage (some vernacular buildings date back to the 1600s), the idea of historic preservation hits close to home for many residents—and that’s exactly what Cornerstones Community Partnerships was banking on when it launched its model for restoring community-owned buildings in 1986. Instead of coming in and taking over restorations, Cornerstones instead works with local residents to develop a plan that suits their needs—and trains them to do the work themselves. “There’s a history of community in New Mexico, and there’s a lot of suspicion about outsiders coming in and doing anything,” explains Cornerstones executive director Jim Hare. “It’s important to go in with that consideration in mind.” Intergenerational learning is a major focus of the approach, giving the youth in the community (as well as youth from various partner programs) the chance to gain a greater appreciation for historic structures from their elders while learning valuable skills via hands-on instruction. “Young people always want to know how they can benefit down the road,” Hare observes. “In our youth training, we emphasize the development of traditional building skills, which can lead to other doors being opened.”

Preservation Greensboro, Inc.

Items for sale at Architectural Salvage of Greensboro’s retail store include column capitals reclaimed from the city’s historic homes.

Often, the most challenging part of a restoration project is pulling together all the little details. Salvage stores can provide salvation—but only if they’re available. Recognizing this need (and also seeing an opportunity to save components from houses they couldn’t rescue), Preservation Greensboro, Inc. formed Architectural Salvage of Greensboro in 1993. “We were all in search of parts for our own old houses—that’s what originally drew us all together,” says Julie Davenport, a longtime PGI member and co-chair of the ASG committee. Run entirely by volunteers, the ASG retail store stocks a wide variety of salvaged merchandise, from claw-foot tubs and pedestal sinks to heart pine flooring and Craftsman windows. A volunteer S.W.A.T. (Saving Worn Architectural Treasures) team goes into homes being demolished to retrieve as many parts as they can, while another group of volunteers gives the items a good cleaning and stocks the store shelves on twice-monthly work nights. For their efforts, the volunteers get credit toward purchases, and proceeds from the store go to fund restoration grants within the community. “People who are into restoring homes find it a great resource,” Davenport says. “I think it encourages people to take it to the next level and restore their houses the right way.”

Historic Seattle

This Foursquare is one of the many homes saved by advocacy activists.

In most communities, conferring protected status on historic homes is an arduous process that often ends in a disappointing dead-end at the city council. In Seattle, however, the task is a little easier, thanks to a law that gives the city’s Landmarks Preservation Board the autonomy to make such declarations. What’s more, Seattle doesn’t require the owner’s consent before it will bestow landmark status, meaning that concerned citizens can take a much more active role in preservation. Enter Historic Seattle and its network of “advocacy activists”—local residents who keep a vigilant watch in their neighborhoods for in-jeopardy properties that can be saved by landmark status. “They’re my eyes and ears,” says Christine Palmer, who heads up Historic Seattle’s advocacy program. “They do a great job of keeping me informed of what’s going on in the neighborhoods.” Twice a year, Historic Seattle offers a full-day workshop to train new volunteers on the fundamentals of landmark designation, and works closely with its existing activists to prepare landmark nominations. “Because owner consent is not required, the nominations need to be legally defensible,” Palmer explains. “If the scholarship is not sufficient, it won’t make it through.” To date, the volunteers’ efforts have helped save more than a hundred of Seattle’s historic buildings.

Historic Chicago Bungalow Association

The Chicago Lawn neighborhood was the city’s first Green Bungalow Model Block.

The media fervor over all things “green” can make concepts like sustainability and energy efficiency seem like just another fad—but for the Historic Chicago Bungalow Association, it’s been a way of life for a while now. When the organization was founded in 2000, bringing energy efficiency to the city’s 80,000 bungalows was its primary concern. “Older homes can appear to be a burden if you’re faced with the increasing costs of energy consumption,” explains Annette Conti, the executive director of HCBA. “If you improve the energy efficiency of the home, you improve the long-term affordability.” Plus, she adds, lower energy bills mean more money for homeowners to funnel into other restoration projects. In addition to offering grants of up to $6,000 for energy-efficient upgrades, HCBA also selects a different Chicago neighborhood each year to serve as its Green Bungalow Model Block. There, restored bungalows showcase such energy-efficient and eco-friendly features as geothermal heating and sustainable cork flooring. Concurrent seminars help homeowners learn how to incorporate these features into their own restoration projects. “We use the model homes as our learning lab,” Conti says. “It gets members looking at issues with their own houses.”

Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation

One of PHLF’s Wilkinsburg homes, after the restoration.

In an age when gentrification seems to blow through old neighborhoods like a tornado, the Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation’s approach to neighborhood revitalization seems like a gentle breeze. Following a model established with its first project in the mid-1960s, PHLF’s Neighborhood Transformation Initiative builds momentum by purchasing a select few properties within a community to rehab. “We develop a plan according to the circumstances we find,” explains Arthur Ziegler, the president and co-founder of PHLF. “We started one neighborhood program with one building; we started another by buying two dozen.” Working closely with community leaders, PHLF uses its own funds to restore the buildings—often investing more than $200,000 in one home—then sells them at a fair price. (Homes in the latest Neighborhood Transformation project in Wilkinsburg sold for as little as $75,000.) These close ties to the community not only keep market values low, but also energize residents to undertake their own projects. PHLF keeps the momentum going by providing education and funds as needed after the major restorations are done. “We’ve never left a neighborhood—we’re still in the first one we started with in 1965,” Ziegler says. “We just try to strengthen the neighborhood so that we take much less of a role.”

Dayton’s Bluff Vacant Buildings Committee

Dayton’s Bluff’s first Vacant Homes Tour spotlighted such abandoned gems as this Queen Anne Victorian.

Home tours are common in historic communities—but most lead visitors through impeccably restored gems. In the Victorian-filled St. Paul neighborhood of Dayton’s Bluff, they do things a bit differently. This May, the Dayton’s Bluff Vacant Buildings Committee (a grassroots group of local residents) hosted its first-ever Vacant Homes Tour, designed to drum up interest in the many neglected properties that have popped up in the community since the housing market took a tumble. “It started as a way to track homes becoming vacant due to foreclosure, but then we started to think, ‘What can we do about these vacant homes?’,” says Matt Mazanec, a real-estate agent and community resident who worked to put together the tour. What they did was use grant money from the city and a local real-estate association to rent a trolley that ferried nearly 400 people around to 11 empty homes. “Some didn’t have electricity, and some had broken windows and graffiti,” Mazanec says. “We weren’t trying to hide the fact that they were vacant. We wanted people to see their potential.” So far, four of the homes on the tour have sold or are pending, and plans are in the works to make it an annual event. “I don’t see a quick end to this crisis,” Mazanec says, “so we’ll certainly have more tours.”