The Swan-Levine house (a former hospital) in all its restored glory.

Like gold-rush prospectors, Howard Levine and Margaret Warner Swan charged into the historic mining town of Grass Valley, California, with determination and a dream. But it didn’t concern unearthing precious metal; they were after something even rarer—a home in which artists could be nurtured and showcase their work.

The genesis of the dream began in 1967, when Howard and Margaret met as art students at San Francisco State University. They married and purchased a 1920s-era stucco home in a nice San Francisco neighborhood. They spent weekends learning how to tend to their old home, remodeling the kitchen and updating the plumbing. They did most of it themselves, but for some work, they hired contractors, taking mental notes of the process.

In 1975, the Levine family’s paper-product manufacturing business was sold. “We were unemployed,” says Margaret, “and we were looking to make a living doing what we love.” They had idealistic dreams about spaces where they could teach students about printmaking, where artists could focus on their media of choice, and where they could display artwork they themselves had made or acquired.

They fantasized about doing it all within a round-trip gas-tank’s distance from San Francisco. Friends told them about an 8,000-square-foot house for sale in nearby Grass Valley. “We took one look at it and said, ‘We can do this,’ ” says Margaret. And, for the bargain price of $63,000, they did.

The young couple with stars in their eyes loaded their two young sons and all their printmaking equipment into an orange Volkswagen bus and drove two and a half hours west into the foothills of the Sierra Nevadas to start a new life in an old house.

The house had an eclectic past. In 1867, local mine owners constructed it as a simple square comprising a library, living room, dining area, and kitchen. The original building burned to the ground in 1895, but was reconstructed on the same footprint. Margaret believes that the fire may have been caused by the new owner’s attempt to keep plants warm during the winter, since he was a horticulturalist. That owner rebuilt the house in the Queen Anne style.

In 1907, a new owner, a doctor, converted the building into a hospital to great local fanfare. “An event of major importance, its grand opening attracted 2,500 persons,” touted the Union Newspaper. “For six hours the crowds jammed the structure,” which was deemed a “magnificent institution.” The house expanded during its tenure as an infirmary. Its back was pushed out and the kitchen was moved, creating a hallway, a storage area, and an elevator shaft. With a sprinkler system installed and an upstairs room outfitted to function as an operating room, the house served as a community medical center until 1968, when its last administrator died, and a modern hospital, built less than two miles away, rendered it obsolete. It sat empty for years, as plans to convert it into apartments went unrealized and neighbors bemoaned the vacancy.

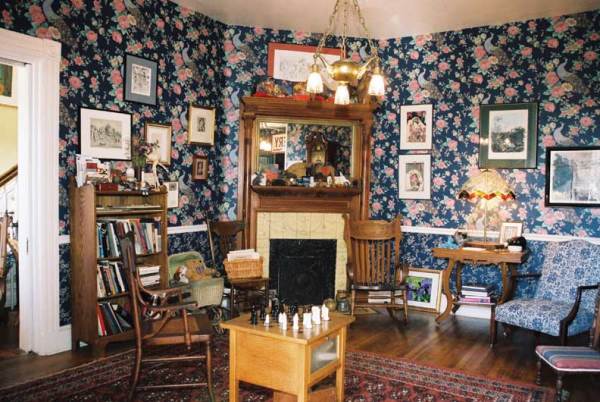

In 1907, the parlor served as the original business office of the Jones Hospital. Though the Victorian-style wallpaper is a new addition, timeless details such as the gleaming oak floors, bas-relief-tile fireplace surround, and mantelpiece remain intact.

When the Swan-Levine family arrived, “It was a white elephant in the neighborhood,” says Margaret. “Nobody knew what to do with it.” The couple chose not to fight the building’s previous incarnations, opting instead to let the spirit of the home’s ever-evolving role in the community inform their renovation decisions. “It’s not a true restoration,” says Howard, who’s active in the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Main Street program at the state level. After all, the house served its community in multiple capacities. “It gave us the opportunity to be a little more flexible,” he explains.

Margaret agrees, “We thought we could tell the whole house’s story through different rooms.” Today the former surgery room serves as a guest suite, and medical cabinets furnish other suites created from former patient rooms. While the house’s grand double pocket doors, wood-and-tile fireplaces, and dual turrets remain true to its restrained Queen Anne styling, practical features like the ceilings were dropped to conceal sprinkler pipes that betray its evolution. Art from every period graces the walls.

Tackling an 8,000-square-foot house with minimal experience and two small children (plus another on the way) would daunt many, but Margaret and Howard had ample help. “About 15 of our friends and family members turned up during that first year or two,” Margaret says. Everyone brought skills—or learned them on arrival. Her brother, Christopher, built the home’s 12-foot-wide front gate and sign. His girlfriend, Wendy, scraped paint from the library fireplace and took up the linoleum that had been laid over oak floors throughout much of the house. Peter, a friend of Howard’s from San Francisco State, brought his carpentry skills, constructing specialized shelving to store lithography stones in the carriage house. Jamie, Howard’s high school chum, cut baseboards salvaged from other areas of the house to replace ones that were missing from the living room.

Margaret and Howard run the breakfast portion of their B&B courtesy of a new, highly efficient wood-burning stove with an antique look. With its open shelving and base cabinetry painted a vibrant, electric blue, the kitchen is a cheerful spot for any artist to start the day.

New friends showed up on their doorstep, too. “One fellow knocked on the door,” says Margaret, “and said he needed a place to stay and he heard we were here.” Howard plays out the conversation, emulating the stranger’s thick Boston accent, ” ‘You got a place I can crash?’ I said, ‘No, but what do you do? ‘ He said, ‘I can do wiring.’ So I said, ‘Well then come back tomorrow and start wiring.’ ” And that’s how they met Byron, who rewired much of the house and eventually brought a girlfriend, Pabby, who, armed with paint remover, scrapers, and steel wool, tackled the old paint on the living room’s fireplace.

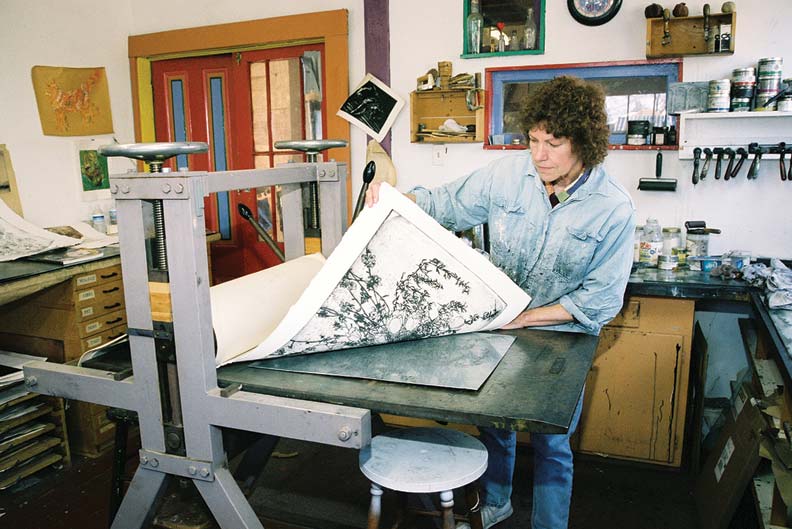

Two years after moving into the main house, their attentions turned to the carriage house, which would serve as the studio they needed to fulfill their art-house dream. The building dated back to 1867, having been spared by the 1895 fire. It had been used as nurses’ quarters for the hospital, but it lacked a proper foundation. “They put a flat rock in each corner and then put the main four-by-fours on top of them,” Howard explains. To remedy the situation, he rented a cement mixer, jacked up the structure, and poured the foundation himself. Then the couple rewired and drywalled the inside, drawing on knowledge they’d gleaned observing contractors at work in their main house. They customized the building for use as a traditional 19th-century printmaking studio complete with specialized presses for lithography and etching. The studio is available for a daily rate that includes instruction.

Work on the house continues, even as it operates as a bed and breakfast that typically hosts eight to 10 people at any given moment. Last year, they hired an electrician to replace the last remaining knob-and-tube wiring.

So what’s next for the Swan-Levine House? Margaret and Howard, who are 63 and 62 years old, respectively, talk about making their first-floor living area accessible for a wheelchair (just in case). They laugh when they suggest that all the people who worked on the house in the ’70s might return in retirement. It would be, in Howard’s words, “Like The Big Chill goes geriatric.” Fitting for an old house with a new lease on life.