The inglenook includes Colonial Revival details: a fireplace crane, original brass andirons, and a parson’s cabinet above the settle.

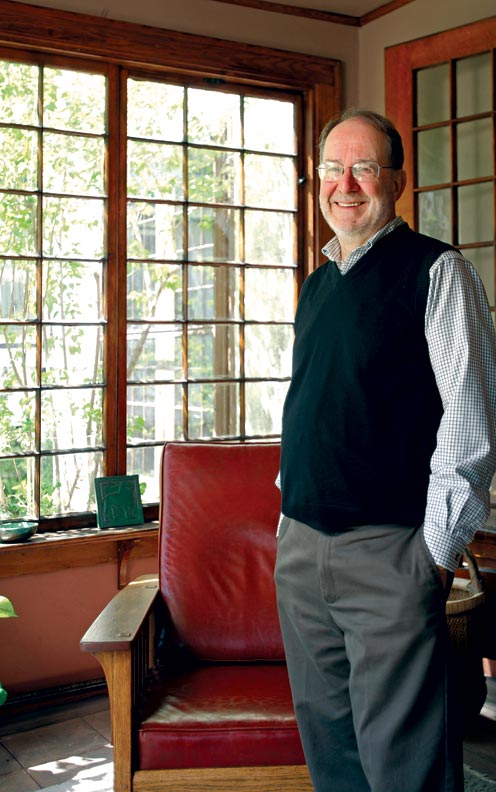

It was 1976 when I first arrived in Scranton to take a faculty position at a local college. Two years later, I decided to put down roots and began to look for a home. After nine months of searching—to the near despair of my patient real-estate agent—I bought an old home in Greenridge, the city’s still-affluent streetcar suburb.

It was a large house with a high, sheltering roof; a massive four-flue chimney; and projecting beams at the gables. The interior was filled with varnished woodwork, including a beamed ceiling in the living room. That room also featured a massive fireplace set in an alcove; chestnut benches resembling those of an old-fashioned soda fountain flanked the hearth. The dining room boasted wainscoting and dentil molding.

One colleague said it reminded him of a fraternity house. Although the house seemed a little pretentious for an assistant professor on a modest salary, I thought it was distinctive, even though I couldn’t quite pin down its style. But I did know it needed work.

Hands-On Training

As I settled in, I began to tackle the needed work with the enthusiasm of a first-time homeowner. My first priority was to insulate the attic with blown-in cellulose during the then-ongoing energy crisis. New triple-track aluminum storms soon followed. In the next summer or two, armed with issues of Old-House Journal, I replaced the sash cords and reglazed the many windows that filled the interior with light and air. With friends, I rebuilt the sidewalks to the front and back doors, learning how to “bring the cream to the surface” for a smooth, professional finish. In time, I found skilled masons to re-plaster the walls and ceilings, which had suffered serious damage as the old house settled. With a local carpenter, I rebuilt the service porch, where an ill-conceived built-in gutter had led to rotted studs. Slowly, the house began to resemble the fine home it once had been.

The house was deliberately sited to face south, filling the master bedroom with morning light and the sun porch with midday sun.

As I worked, the carpenters, plasterers, and bricklayers who labored with me praised the quality of materials and the craftsmanship with which my old house had been built. The joists were a solid 2″ x 7½”. The bricks forming the keystone in the arch above the firebox had been shaped by hand. The same bricks were used for the doorsteps and copings outside, unifying the interior and exterior. The back hall tile had been laid by hand, as a few mislaid tiles in the border pattern attested.

There were other very human touches that lent character. Whoever designed the house had failed several times to provide adequate clearance between drawers and doors—when you opened one, the other had to remain shut. An exterior vent for a living-room radiator had been sealed—probably after the first winter’s drafty use. Instead of swinging out, the sun porch windows pivoted open on a point at their center. These quirky features, evidence of the designer’s otherwise expert hand, I appreciated and preserved.

Craftsman Appreciation

The Colonial Revival-style dining room includes a built-in buffet; the center panels slide open to provide a convenient pass-through to the pantry beyond.

Though I could clearly see the house had been constructed with care, it wasn’t until I read a piece on Gustav Stickley in Old-House Journal that I began to realize exactly what I had. The fireplace recess was an inglenook—that icon of Arts & Crafts architecture. The house’s built-ins—bookcases, the fireplace benches, and dining room buffet—were typical of the style on which Stickley drew. So, too, were the beamed ceiling, the massive hearth, and the integration of indoor and outdoor living spaces.

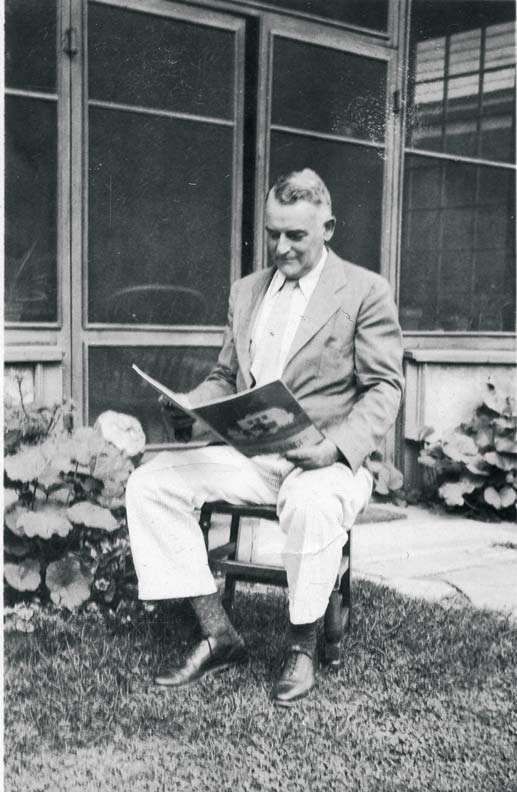

By then, I had acquired a copy of the city’s 1915 building permit and knew the house had been designed by its original owners, William H. and Dorothy Scranton, as a young couple. I began to make inquiries to their family, neighbors, and friends. William, I soon learned, was the grandson of George W. Scranton, one of two brothers who founded the city. Dorothy was the descendent of Yankee merchants and missionaries to China, and was still warmly remembered for her charm and droll sense of humor. Well-educated—he at Princeton and Cornell; she at Cooper Union—they raised two successful children and were avid gardeners, active members of the elegant Gothic Revival church down the block, and walkers (they never owned a car). Try as I might, however, I was unable to establish a direct link between the house and Stickley or the American Arts & Crafts movement.

Yet there were hints. The house’s casement windows featured the Bulldog hardware Stickley had advertised in the pages of his Craftsman magazine. Mr. Scranton had done a grand tour of Europe as a young man in the 1890s, where I thought he might have been exposed to the movement. Most telling, however, was his 30-year career as an instructor in mechanical drawing at the city’s manual training high school. A member of its founding faculty, he had spent 1905 touring manual training schools where the Arts & Crafts movement in the U.S. had flourished. While the Scrantons, according to their daughter, had merely “included things in the plans that they liked,” they had nonetheless produced a noteworthy example of American Arts & Crafts architecture.

In the meantime, I purchased an L. & J.G. Stickley chair in Syracuse on a dare from my sister-in-law. It clearly suited the house. I then began to pick up pieces of Stickley and Roycroft when I could. I attended auctions (once at the same time as Barbra Streisand), hung out in Soho with the dealers, got to know some pickers, and even hosted Robert Judson Clark—the Princeton scholar who revived the interest in the Arts & Crafts movement—in my living room.

Mrs. Scranton requested the bedroom fireplace and built-ins. The bed and side tables are by Gustav Stickley.

I also explored the Arts & Crafts heritage of the city of Scranton, discovering Grueby tile murals in the former Lackawanna, Delaware, & Western station and a Tiffany mosaic in St. Luke’s Episcopal Church. I found out that an elegant nearby home had been designed by architect George Dietrich, once affiliated with The Craftsman.

I came to appreciate the streetcar suburb the Scrantons had selected for their home. Just as they had done, people still strolled along the sidewalks, chatting with neighbors as they passed. Neighbors borrowed tools, shared information about schools and politicians, and referred one another to the carpenters, plumbers, and other building tradesmen old-house owners depend on. While the automobile had altered the social life of adolescents, the large church hall where local teenagers had once bowled, played basketball, danced, and just hung out still stood beside the church down the block. The ideals of the Garden City movement, an extension of the Arts & Crafts movement, were still being realized here.

Over time, I came to realize that the house I inhabited had opened a window for me into an otherwise vanished lifestyle and aesthetic. As the years passed, I grew to admire the Arts & Crafts movement—not only its commitment to good materials, craftsmanship, and simplicity of design, but also its belief in the creative potential of every human being. Living in a home inspired by it, the movement’s legacy had come to touch and enrich my life. It was much more than I had ever expected of an old house in Scranton.