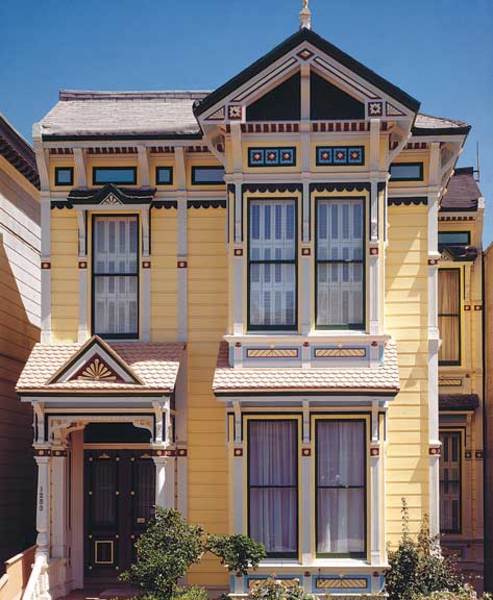

Stick stayed stylish all through the 1890s in San Francisco, bringing intricate, Eastlake-inspired façade ornament to countless wood row houses. (Photo: Douglas Keister)

Just before the Civil War, when it seemed like residential iterations of Old-World architecture would parade on and on through the rest of the 19th century, there appeared a new house style that, while clearly influenced by history, also hinted at something different. The Stick style, as it is now called, represented the most innovative design concepts and building technologies of its time, yet it did not attract serious study—or even a widely accepted name—until a century later. Were it not overshadowed by the equally extroverted Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne styles by the 1880s, and through much of the 20th century, it’s clear that the Stick style would have been recognized much earlier for its original identity and the totally American concept of a house that it presented for the first time.

Making Them Stick

Today historians often call Stick a transitional style, a bridge between the picturesque Gothic of the 1840s and ’50s and the full flowering of Victorian ideas in the Queen Anne houses of the 1880s and ’90s. While such a perspective is academically accurate generations later, in its day the Stick house was nothing if not totally fresh, up-to-date and, most of all, modern. While some critics found them slightly vulgar, few could deny these houses were inventive and vivacious. People of wealth and standing wanted them; the public accepted and built them. Stick houses were high-concept buildings that capitalized on the best resources of the era.

A textbook example of the Stick style for the average family is this house in Albany, Oregon, with its gavle end nicely delineated by pronounced stickwork. The grid of vertical and horizontal boards seems to support the windows and wall, while diagonal boards in the eaves “brace” the roof. (Photo: Kenneth Haversen)

Many Stick houses were architect-designed, and the brightest talents in the newly prominent architectural profession were attracted to the style. Richard Morris Hunt, the Ecole des Beaux Arts-trained architect to America’s newly minted gentry, chose to work in the Stick mode for Newport cottages. Early in his career he designed at least two: the T. G. Appleton House (1875) and the J.N.A Griswold House (1862), a textbook example of the style. Philadelphia’s Frank Furness took readily to the idiom for the 1878 estate of Emlen Physick, a prominent bachelor physician who built a Cape May, New Jersey, house for his extended family. Other notables who tried their hand in the style include Richard Upjohn, famous for New York’s Trinity Church, and Henry Hobson Richardson, the seminal designer of the Romanesque and Shingle styles, as well as his own Trinity Church in Boston.

What propagated the Stick house at the popular level, however, was the spate of new house-building plan books that appeared after 1850. Architect-publishers like Gervase Wheeler and Henry Cleaveland flashed the Stick look far and wide in their books Rural Homes (1854) and Village and Farm Cottages (1856) as part of a broad menu of building designs. These plans inspired local builders to erect Stick houses, or incorporate their details, on a truly national scale for the first time, from the established Northeast to the burgeoning cities of the West like San Francisco.

Ultimately, Stick-style houses are about carpentry—the latest advances in wood technology from a country that had lots to offer. Unlike chunky, ground-hugging Gothic and Greek Revival houses that emulated the massing of masonry even when built of wood, Stick-style houses are generally light and irregular in feel—a freedom of form made possible by the new system of balloon-frame construction with 2 x 4 lumber and nails. Rather than dividing the space within a simple rectangular or cross-shaped plan into rooms and halls, Stick houses seem to push the space beyond the footprint—so much so you can often read the interior space from outside the building. Projecting bays, gables, and porches are common in Stick houses as are towers and dormers. Roof plans are complex—often very much so with intersecting gables and roof effects, such as clips, hoods, and kicked eaves—a regular repertoire in the most full-blown examples.

Even with a straightforward plan, this Haddonfield, New Jersey, house employs Industrial Age millwork—chamfered porch posts and eave brackets combined with fret-sawn balusters and trusses—to delightful Stick effect. (Photo: James C. Massey)

Like the Queen Annes to come, Stick-style houses generally exhibit a strong vertical emphasis, with tall windows, multiple stories, and surface ornament reaching skyward along with sharply pitched roofs and monumental towers. More than Queen Annes, however, Stick houses are angular. Window bays and towers are generally squarish, with roofs that are pyramids or similar polygons.

The defining feature of these houses, however, is stickwork: expressive wood facing and ornament that evokes the grids and angles of structural framing in their layout. In Stick houses, the exterior clapboards and shingles are divided into panels by vertical and horizontal boards, bringing the symbolism, if not the actual position, of the underlying posts and joists to the façade.

Diagonals are common, enhancing the structural feel with a hint of the medieval. Often the beaded siding found within rectangular panels is also laid diagonally and mirror imaged in an adjacent panel. More diagonals pop up as pseudo-structural brackets supporting roof eaves or trusses spanning gable ends—woodwork that was easy to mass-produce with new steam-powered machinery. Curves are rare except for the periodic semicircular porch bracket or window top.

Sticking to Sources

San Francisco’s famous Westerfield House (1889) is a good example of how a tower and repeated vertical stickwork enchance the verticality of an already tall building. The sawtooth board-ends on the olive-colored, second-story “frieze” are a classic Eastlake motif. (Photo: Douglas Keister)

Though a mix of technical innovations and stylistic references all came together in the Stick-style house, architectural historians have often spied many precursors in the Gothic Revival houses of the 1840s. The noted scholar Vincent Scully, whose 1955 paper The Stick Style and The Shingle Style put both houses in the 20th-century landscape, traced many of these ideas—particularly the growing embrace of all-wood construction and the visual effects it made possible—to Andrew Jackson Downing.

Through his widely read books, Downing became America’s first popularizer of the country house and the Picturesque movement—the romantic appreciation of the wild and rugged natural world. He did much to whet the architectural taste for bold features and striking outlines that would become an addiction by the 1880s. Downing was a particular advocate of Swiss cottages, which he deemed the most picturesque of all dwellings built in wood. He liked the widely projecting roof, pronounced brackets, and abundant galleries and balconies of these mountain dwellings, and proposed that subdued versions were ideal for enhancing the comfortable quality of a house, even where a lack of heavy snowfalls or rugged terrain made them unnecessary.

Downing’s soft spot for the Swiss way with wood extended to the shingles that clad the walls, a method he found as attractive as it was durable. Shingles cut in ornamental patterns produced a more tasteful and picturesque effect than common vertical-board siding, he said, adding visual interest and spirit to the building. In fact, the now famous Swiss-cottage design featured in one of his most popular books, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), shows a broadly roofed house finished in fish-scale shingles that are crisply divided at intervals by vertical boards—the prototypical cladding of the Stick-style house to come.

Downing was not alone. His vision of charming, picturesque houses with fanciful details continued to ripple through the 19th century long after his accidental death in 1851. While being versatile in a spectrum of exotic styles was good business for an architect in the 1850s, the expressive, honest use of wood in the Swiss cottage and its homey, domestic scale and feel, struck a resonant chord with a building public that lived in a land of wood, and clearly bubbled up in the wood buildings to come throughout the Victorian era.

Stylistic Subtleties

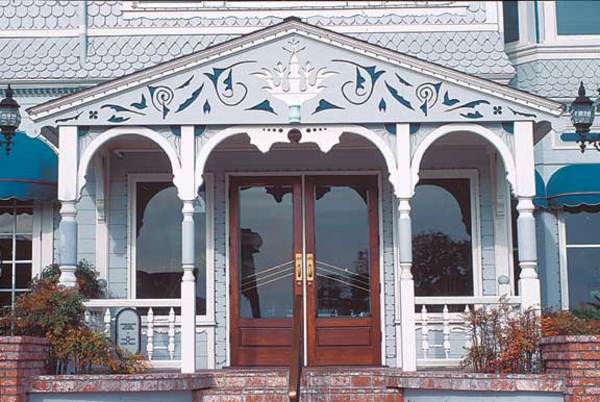

Perfection of the power bandsaw is what made intricate cutout work like this porch pediment not only possible, but affordable. Semiautomatic lathes could turn hundreds of identical posts, regardless of their complexity. (Photo: Kenneth Haversen)

Historians have also noted that Downing and his contemporaries coveted what they called character in a building—a quality about as removed from how we use the word today as calling an ironclad steamship cool. In a 19th-century context, building character was roughly analogous to human character—not an ideal of beauty or theory, but a richness in individual personality or identity. The sharp angles, broad roof overhangs, and unexpected voids of the Stick style and the deep shadows they produced certainly filled the bill. Galleries and porches provided particularly ample opportunities for dark, cavernous recesses, giving these features a new importance in the design of a house.

No less an influence, especially later in the life cycle of the Stick house, were the ideas of the English tastemaker Charles Locke Eastlake. Though Eastlake’s original critical remarks were directed at reforming the design of English furniture and furnishings, by the time his widely read columns and book Hints on Household Taste (1868) had filtered across the Atlantic, they found traction not with the furniture industry, but the house-building public. His call for furniture ornament that was simple, finely crafted, and closely related to the structure of the object materialized as exterior building millwork that was aggressively turned, sawn, and carved—a turn of events that appalled Eastlake himself. The Stick house was the first style to take this millwork to heart with incised verge boards, fret-sawn railings, and porches ringed with spindles.

A century after it first came into fashion, the Stick style rode the crest of a new, different wave of modernity during the psychedelic era of the late 1960s and early ’70s. By then many of the once-patrician Victorian neighborhoods of San Francisco had become the low-budget, bohemian haunts of the counter culture. Scores of forgotten Stick row houses emerged from the doldrums emblazoned in electric paint colors that highlighted their nearly forgotten façades of crisp, contrasting patterns and lively, constantly shifting planes. The widely popularized rebirth of San Francisco’s Painted Ladies not only catalyzed the growing interest in Victorian architecture, it also helped widen the appreciation of all old houses for decades to come.

Published in: Old-House JournalMay/June 2003