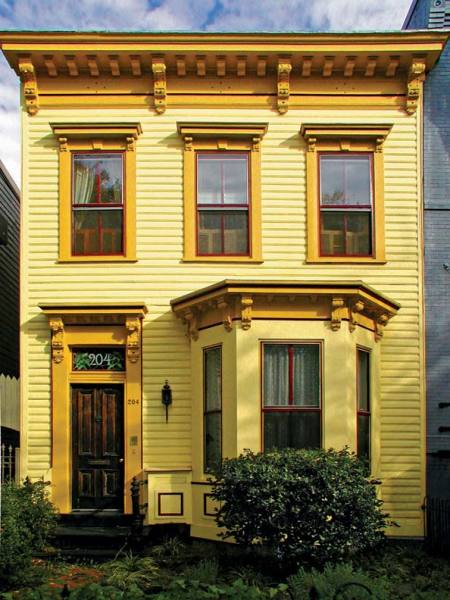

Painted in the warm earth tones typical of the period, this Michigan Italianate is small, but still bursting with ornamentation. (Photo: Joe Hilliard)

Books and products mentioned in oldhouseonline stories are chosen by our editors. When you buy through links on this site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

In the optimistic quarter-century before the Civil War, adventuresome American homebuilders had more design options than ever before in the nation’s history. In fact, they faced a veritable architectural smorgasbord of styles.

On the one hand, they could embrace the reassuring but confining symmetry of Greek Revival architecture, secure in its uplifting symbolic references to our own young republic. Alternatively, they could exercise the exoticism of the picturesque Gothic Revival, so popular with reformers in Great Britain and Europe because of its supposed connection to the aesthetic and moral “purity” of medieval churches and cottages.

Or, they could opt for one of the up-to-date “Italian” styles—every bit as romantic as the Gothic Revival but infinitely better adapted to the freer (and more family-oriented) lifestyle of an increasingly large and prosperous middle class. The Italian villa, an impressive, square-towered, irregularly shaped mansion with deep eaves, was based on the northern Italian country houses of Tuscany. The style celebrated wealth and modernity, two characteristics widely embraced by a burgeoning middle class. Its cousin, the Italianate “bracketed cottage,” was a bit less ostentatious, yet stylish enough for a new generation of homeowners.

Most folks chose option three. From coast to coast, north to south, the Italianate was America’s most popular house style from about 1840 until well after the Civil War.

Middle Class Mania

A middle-class row house in Washington, D.C., is typical of thousands built in post-Civil War America. (Photo: Bruce Wentworth)

There’s no denying that Italianate architecture was often merely a way to apply fashionable ornamentation and interesting shapes to traditional center-hall houses—which was good news for the culturally timid. In more ambitious hands, however, the style could readily become the means of providing flexible, asymmetrical floor plans that made home life easier for families.

The Italianate style swept into America’s consciousness on a tsunami of advice books about modern life, morality, and architecture. Social and aesthetic reformers rushed to give the new middle class a crash course in the finer points of 19th-century living. Their advice on one point was unequivocal: Get out of the big city before it’s too late!

Nineteenth-century thought was focused on the family with unprecedented urgency, and for good reason. As the Industrial Revolution matured, it produced an astounding population explosion in America’s cities. (One source cites an urban growth rate of 700 percent in the 30 years before the Civil War.) Dirt, disease, crime, and pollution made American cities unsuitable backdrops for family life. The countryside and the suburbs, on the other hand, offered an excellent counterpoint to these urban ills—at least for those who could afford to move to the country. Well-designed, “tasteful” houses like the villa and the bracketed cottage were essential to a happy, healthy suburban existence.

Restrained in its ornamentation, this Vermont home relies on a fine hooded entry sheltering fancy double doors for its decoration. (Photo: Carolyn Bates)

The Visionaries

The most influential advocate of the Italianate style in America was A.J. Downing, an energetic young landscape designer and pattern-book author from Newburgh, New York. His books, Cottage Residences (1842) and The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), were widely distributed and eagerly consulted for their drawings and descriptions of houses, floor plans, and landscaping that suited the changing times.

Downing was primarily a landscape designer and social reformer rather than an architect. He relied heavily on the designs of others, notably the English-born Calvert Vaux and fellow New Yorker Alexander Jackson Davis, to illustrate his books. (Both Vaux and Davis produced their own architectural-pattern books as well as contributing to Downing’s.) That is not to say that Downing was committed solely to the Italianate style, however. Until his untimely death in 1852 in a Hudson River steamboat explosion, he remained true to his Gothic architectural ideals—so much so that the era’s distinctive, small, Gothic Revival houses are frequently referred to as “Downingesque.” Nonetheless, his presentation of the work of Vaux, Davis, and others in the Italian style gave enormous impetus to the style’s popularity.

In keeping with their interest in promoting healthier lifestyles and higher aesthetic standards, Downing, Vaux (in Villas And Cottages, 1857), and Davis (in Rural Residences, 1837), along with other pattern-book authors, envisioned Italian villas set in generously spaced, “naturalistic” rural landscapes rife with vegetation and towering evergreen trees. As it happened, though, most Italianates were built on smallish town or city lots, often quite close to neighboring buildings.

Built in 1859, Ashton Villa in Galveston, Texas, is one of the country’s greatest Italian mansions. (Photo: James C. Massey)

Downing particularly admired the Edward King House, a grand brick villa built in Newport, Rhode Island, in 1845. Its architect, Richard Upjohn, another English transplant, is best known for his Gothic church designs, but like many architects—including Vaux and Davis—he worked in both Gothic and Italian styles. The King House is one of the earliest and most striking American examples of the villa. It displays a nearly perfect array of Italianate features, including a massive four-story tower; an asymmetrical but harmonious mix of porches, wings, and balconies; deep, bracketed eaves; and a panoply of round arches.

Other notable architects who practiced in the Italian style include John Notman of Philadelphia, who is credited with designing the very first Italianate villa on this side of the Atlantic in 1839, the Bishop George Washington Doane House in Burlington, New Jersey. Henry Austin of New Haven, Connecticut, was responsible for the great Italian villa now known as the Morse-Libby House (Victoria Mansion) in Portland, Maine, built in 1858. A year later, Philadelphia’s Samuel Sloan designed an entire block of Italianate houses (Woodland Terrace) in Philadelphia. In North Carolina, A. J. Davis designed an early villa, Greensboro’s Blandwood, in 1844. Orson Squire Fowler, the phrenologist and octagonal-house enthusiast, used Italian ornament on his constructions—and indeed, most octagonal houses are trimmed in the Italianate manner.

Flexible Flourishes

Compared with many houses of the period, this one in Dowagiac, Michigan, is rather plain, yet its projecting cornice marks it as Italianate. (Photo: Vickie Phillipson/Greater Dowagiac Chamber of Commerce)

The floor plans recommended by the era’s Italianate trendsetters were relatively flexible, with multiple means of access to the outside, free-flowing interior passages between rooms, and varied opportunities for cozy nooks and family gathering spaces, as well as clearly defined public areas.

No matter how Italian the exterior, furniture and interior trim were often Gothic in style—or French, English, even Egyptian. “Italianate” is not a term easily applied to the decorative arts.

Decoration on the Italianate exterior was no less fanciful. Advances in technology made the production of decorative cast-iron ornament easier and cheaper, so it shows up frequently on balconies and porches, as well as in fences and roof cresting, whether in rounded Italian designs or in Gothic or Classical ones. Villas always had the added feature of at least one square, multi-storied tower and, for the most part, decidedly asymmetrical massing.

As the architectural eclecticism of the postwar era enveloped America, the appeal of Italian style dimmed, but took its own sweet time to leave the scene completely. As late as 1876, the style was featured in Atwood’s Modern American Homesteads, and the book’s back pages carried an advertisement for Bicknell’s Village Builder, proudly displaying a gloriously ornamented Italian house. Soon enough, however, a new national craze arose, and the Queen Anne and other High Victorian styles swept the Italianate permanently aside.