A grand Georgian Revival house has its roots in Virginia’s 18th-century James River plantations.

Unlike many planned subdivisions, Guilford—northeast Baltimore’s deeply coveted residential oasis—did not spring into being with a single impetuous leap. Instead, it evolved slowly, gracefully, and with unwavering intentionality. Its 210-acre expanse was planned and platted well in advance of construction, its landscape as carefully thought out as its houses. Guilford took shape over nearly 40 years—from 1913 to 1950—and came to include 800 houses in a dozen or so architectural styles; its charm and distinction remain intact.

While Guilford’s near neighbor, Roland Park, developed at the end of the 19th century and reflects a late-Victorian aesthetic (with Queen Anne, Shingle Style, and early Colonial Revival houses), Guilford, also owned by the Roland Park Company, moved into the 20th century with up-to-date versions of the Colonial Revival, and also added American and English Arts & Crafts and Old English styles.

The 1920s and early ’30s brought a spate of new construction that resulted in an array of between-the-wars eclectic revival styles, as well as more academically accurate versions of Colonial and Georgian Revival. After the Depression and World War II, attention centered almost exclusively on the Colonial Revival, now pared down to accommodate shortages of cash and materials—and also to fit a growing taste for simplicity.

Thoughtful Planning

Old English designs are common; this formal Jacobean house features battlements, buttresses, and Tudor arches.

Many of the houses are set on commandingly high lots, but all except the very largest have identical setbacks, a practice that, combined with an orderly tree pattern, lends regularity to the streetscape. No electric lines or telephone poles mar the effect; they are tucked out of sight underground or behind the houses. Since Guilford was an automobile-era development, many houses have small garages matching the house style. A few churches and a single school are old Guilford amenities, but there are no commercial buildings—no loss, since businesses abound on surrounding streets.

The houses vary in size and character, from sedate brick rows to cozy Cape Cods to imposing Georgians, with a few outright mansions lording over mini-estate-sized lots. Building materials are mostly brick, stone, stucco, and half-timbering, with some frame and shingles.

The remarkable charm and consistency of this multi-style development grew out of its founders’ broad vision and careful oversight; in order to protect the high-quality materials, design, and construction that built Guilford, an equally high standard of maintenance continues to be enforced. For instance, Guilford’s ubiquitous slate and terracotta tile roofs are essential components of its character, and their repair and replacement are rigorously controlled by the Guilford Association, legal successor to the Roland Park Company. Consequently, on many quiet afternoons you can hear the gentle tap-tap-tap of the slater’s hammer as it shapes, sizes, and places the slates, making its own music, accompanied by a chorus of Guilford’s church bells ringing the hours.

A fine Arts & Crafts house shows a very steep two-story gable and variegated slate roof.

Differing Styles

Many of the earliest home designs came from Edward L. Palmer, Roland Park’s architect, but buyers also were encouraged to select their own architects with the approval of the Roland Park Company. Thus, a number of talented architects brought their skills to bear in Guilford, including the nationally prominent Classicist John Russell Pope and Baltimore’s own Laurence Hall Fowler.

Some early houses show the influence of English Arts & Crafts luminaries like C.F.A. Voysey and H.M. Baillie Scott. These houses have asymmetrical massing with sections of varying heights, sometimes combining a steeply sloping roof on one section with a flat main roof, plus lower shed-roofed end sections. Their flat wall surfaces of stone or stucco are often punctuated with prominent entries framed by massive swans-neck-and-pineapple pediments, decorative wall plaques, multiple-paned leaded casement windows with stone frames, and tall chimneys topped by terracotta chimney pots.

The American Arts & Crafts house prevalent in Guilford is smaller, less formal, and more domestic in appearance. It is picturesquely asymmetrical, usually with multiple gables. Guilford’s examples most often have stucco walls. Timber-framed entry porches sometimes add to the picturesque effect, and casement windows are often grouped in ribbon-like arrangements.

Half-timbered Old English (a useful term that includes Tudor, Elizabethan, and Jacobean styles) cottages and houses have brick walls with smooth stucco infill between exposed horizontal and diagonal braces of dark wood; casement windows; and often multiple gables and steep catslide roofs.

This Old English house uses half-timbering, stone, and stucco in a picturesque design of the 1920s.

Guilford’s French or Norman Revival houses typically feature at least one rounded corner or entrance turret, as well as steep, hipped roofs pierced at the edges by segmental arched dormers. They also might have a formal, segmental-arched entrance of stone, as well as one or more one-story bays sheltered by outward-curving metal awnings. Walls are generally stone or stucco.

Italian, Spanish, and Mediterranean sources provide the inspiration for the lightest and brightest of Guilford’s houses, with their white or cream-colored flat walls and orange or green terracotta barrel-tile roofs. The Mediterranean Revival is the most formal, symmetrical, and ornamental of the three, while Spanish is the least. Italian and Mediterranean characteristics may blend almost seamlessly, but the deep eaves of the Italian and the ornately decorated flat walls of the Mediterranean provide some clues to the architect’s intentions. Spanish houses have no trim surrounding their deeply recessed round-arched doors and windows, but the doors themselves are bold statements in dark-stained wood with large strap hinges. Arcaded porches are typical, with small, wrought iron faux balconies at the second floor.

Old Favorites

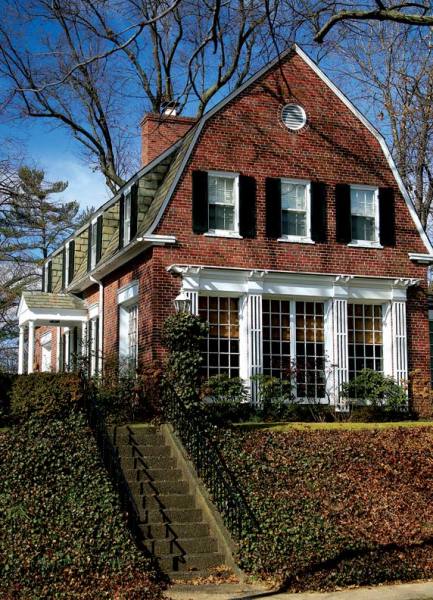

In an unusual twist for the neighborhood, this Dutch Colonial turns its gambrel-roofed end toward the street.

It is the Colonial Revival that forms the architectural heart of Guilford. This perennial American favorite is everywhere, in brick, stone, stucco, and frame, in every sub-style found in the Northeast. Its evolution can be traced from 1913 to 1950 on Guilford’s streets. Baltimore’s love affair with the row house is represented in Guilford in the suburb’s earliest houses.

Ranging along the eastern boundary of the community are a number of short rows of small Colonial Revival dwellings, often grouped around quaint courtyards, like tiny colonial villages. In the 1920s and ’30s, single-family, relatively informal Colonial dwellings of rubble fieldstone or red brick were extremely popular here, boasting gabled slate roofs and dormers with small-paned, double-hung sash. The occasional Dutch Colonial, identified by its signature gambrel roof with continuous dormers, might be of stone brick, stucco, or frame construction. The postwar version of Colonial Revival, also of brick or stone, is plainer and lower, with flatter wall surfaces and less decorative detail.

The diminutive but durable one-and-a-half-story Cape Cod cottage, beloved in the 1930s and later, is here usually found in brick, with a slate roof and slate-sided dormers—not a pure version of the style, but charming all the same.

The Georgian Revival house—formal, large, and often further expanded by lateral wings—displays elaborate period detailing, especially at the entry. Topped by a hipped or end-gable roof, it is usually of red brick but sometimes of stone.

Several Spanish Colonial Revival houses add to the variety of styles in the Guilford Historic District.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2001, Guilford is looking forward to a grand centennial celebration in 2013. If you visit this year, you’re likely to find Guilfordians busy in their yards and parks, planting, replanting, and caring for their neighborhood’s leafy heritage, still guided by Olmsted’s century-old tree-planting plan. If you happen to be there in the springtime, you might be dazzled by the kaleidoscopic glory of 80,000 tulips blooming in Guilford’s famous Sherwood Gardens (just east of the 4100 Block of St. Paul’s Road). If you can’t get to Guilford before summer, rejoice in the splendor of Sherwood’s thousands of annuals in resident-tended plots. And, of course, any time of year is a great time to enjoy a self-guided strolling tutorial on Guilford’s eclectic architecture of the first part of the last century. If you’re really rushed, start with the unit block of St. Martin’s Place—then come back to see why some folks just can’t stop looking at Guilford.