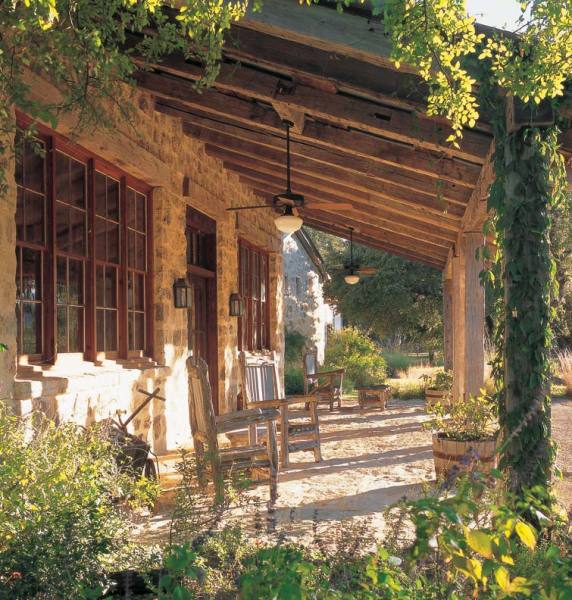

Ceiling fans on the porch provide cool breezes during the long Texas summers.

When Ignacio Salas-Humara’s client requested a new home that would look 150 years old when finished, it was the first time that the south central Texas architect was asked to design a historical house…not just a historical-looking house. “My client really wanted everything to be as accurate as possible,” says Salas-Humara. “He wanted to go the full mile.” So for inspiration and to conduct extensive research, he headed a few hours northeast of the construction site to Fredericksburg, where the 40-block Historic District is one of the earliest Germanic settlements in the state.

Founded in 1846, Fredericksburg welcomed the first generations of German settlers. Seeking land and opportunities, they arrived with an arsenal of Old World building traditions and skills. As the immigrants adapted to their new environment, they crafted what they could, incorporating what was available and learning from each other. They saw potential in the indigenous raw materials in this Texas Hill Country region of tall, rugged hills made of limestone or granite, covered with thin layers of soil.

At first the Germans copied the log houses being built by transplants from the East Coast. Eventually, they quarried the abundant limestone around them to build strong rock houses. Walls of hewn stone masonry were common in Hessian and Frankish regions of Germany, where such stonework typically appears in the ground floor of the house, and upper levels display fachwerk, also known as half-timbering.

In Fredericksburg, Salas-Humara was struck by the number of multi-structure residential compounds he saw. “A family would maybe start with a log cabin, add a barn…with [financial] success they added on,” observes the architect. “The houses organically grew like that.” Fredericksburg is a “gold mine of this type of architecture,” says Salas-Humara. It is not unusual to find all three building phases—log, half-timbering, and stone—in individual German houses with successive additions.

Exposed stone walls and salvaged flooring create a home that looks as though it has existed for more than a century.

Inspired by Fredericksburg’s vernacular architecture, Salas-Humara built for his client a 7,000-square-foot compound located on a 500-acre ranch outside the historic town of Medina, 275 miles from Fredericksburg. It sits on a limestone bluff overlooking the west fork of the Medina River, a serene waterway shaded by cypress trees and favored by canoeists. Referencing his research, Salas-Humara settled on the concept of a generational farmstead. “It was conceived as a whole to produce the effect that each piece—the log cabin, the main house, the water tower, the carriage house—was built separately over time, added onto, and connected to the others over the last century and a half,” he explains.

According to the architect, the ranch’s main house was designed to resemble a much larger version of a typical German stone house. In his book, Roots of Home, Russell Versaci calls it a “pumped-up version of a Hill Country ‘Sunday House.’” These small weekend retreats in town were often built of fachwerk. But Sunday Houses were small and did not include a central hallway, whereas Salas-Humara’s much larger structure does. It is a high-roofed, one-story house with a commodious loft, displaying a classic layout with parlors to the left and right. Old, hand-hewn oak beams dominate, and 18″-thick limestone walls provide superb insulation in summer and winter.

A collection of primitive pottery and farmhouse antiques fills the space.

Eating, cooking, and casual living take place in a large rectangular room on one side of the center hall. Everything about the room is historically accurate, from the custom kitchen cabinetry to the blacksmith-forged iron hooks for hanging pots. Citing a modern refrigerator housed in an old wooden hutch, the architect stresses the importance of making the home workable by today’s standards while maintaining the historic look and feel. A modern stainless-steel stove is tucked into a stone nook, with stacked stone overhead concealing the range hood. The floors of sanded, rough-sawn wood cut from antique timbers were stained using three colors to give them just the right patina of age.

Read more about this house’s kitchen

For the children’s bedroom wing, Salas-Humara looked to the Anglo-Americans streaming in from the Appalachian highlands, bringing their heritage of dog-trot log cabins—two one-room cabins built with an open breezeway between them, all under one roof. This style of house, also known as a breezeway house, dog-run, or possum-trot, was common throughout the southeastern United States during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For this Medina structure, Salas-Humara had an original shipped from Kentucky and reassembled. The architect filled in the open breezeway area—the dogtrot—with bathrooms and closets.

In the bedrooms, exposed log walls are the height of the original cabin, nearly two stories, which allows for a loft space above. Cabins like these typically had logs cross-stacked at the corners, a practice that left spaces between the logs that were filled in with clay-and-lime mortar. This “chinking pattern,” says architect and historian Versaci, “is distinct in the Hill Country.”

A cistern—a ubiquitous fixture in the 18th and 19th centuries—is used today for irrigation.

A short corridor connects the children’s bedroom wing to a two-story garage that resembles an old western bunkhouse and stone wagon barn. The client wanted a four-car garage that, when cars were removed, could be used as a party space. The garage is authentic to the 1800s, with wooden swing doors sporting hardware made by a local blacksmith. For everyday use, there are also four conventional overhead garage doors covered in old barn wood. “We got the look and authenticity and also convenience,” explains Salas-Humara.

This desire for accuracy down to the smallest detail also influenced the building of a water tower on the ranch. In the 18th and 19th centuries, these ubiquitous cisterns of cedar and cypress, capped by a corrugated metal roof, provided water for drinking as well as putting out fires, if necessary. “[This one] was originally going to be fake, but the owner wanted a real one,” says Salas-Humara, pointing out that today the water is used for landscape irrigation.

With its axe-scarred antique timbers salvaged from old barns, rusted metal porch roof, old wavy window panes, and materials like tight-ringed long leaf pine (which doesn’t exist anymore), this Texas Hill Country ranch could be the setting of a John Wayne western. But unlike a hollow movie set façade, the rigorous historical detail continues when you walk through the door, distinguishing the accoutrements as well as the interior structure. “Just about every single thing is recycled,” says Salas-Humara. “Even the rock.”