The 18th-century house was moved 11 miles to its current location on Bayou Chenal.

Deep roots in Louisiana nourished Pat Holden’s love of this area’s architecture, culture, and landscape. For decades she has been immersed in the history of Pointe Coupee parish. She and her husband, Dr. Jack Holden, have assembled quite a collection—of buildings as well as furnishings. The centerpiece is a late 18th-century house set within a semicircle of centuries-old oaks. They found the house, slated for demolition, nearby in New Roads; they moved it 11 miles after the owner, happy it would remain in the parish, sold it to them.

Reassembled and beautifully restored, it sits now on Bayou Chenal, a tributary of False River. Dependencies, or outbuildings, dot the back pasture; there’s a barn, a henhouse, an overseer’s cottage, a pigeonnier, a kitchen and laundry building, and a garçonnière (young men’s quarters). Chickens are free-range, and a mule and horse graze in the pasture.

The Creole experience is deeply ingrained in the house and its collected furnishings, in the garden, and even in the animals kept. The Holdens’ knowledge was gleaned from the buildings themselves, and from their extensive study of historic records in libraries and courthouses. They have pored over 19th-century letters and the memoirs of long-ago travelers. In this project, accomplished over decades, they acted as their own architect, contractor, interior decorator, and landscape designer. (Jack’s book, Furnishing Louisiana: Creole and Acadian Furniture 1735–1835, was published in 2010; it’s regarded as the authoritative reference on the subject.)

“We’re caretakers of the house,” Pat says. “No sense having an old house and taking away its history.” She says their challenge was to feel a true connection, to be aware of the ties that join past and present.

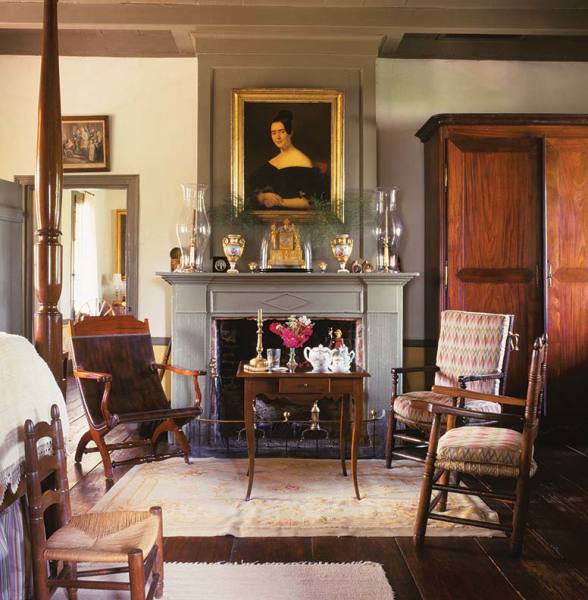

Every building has been suitably furnished; objects range from high-style French antiques brought to Louisiana by 18th-century settlers to vintage farming implements made by local craftsmen. Some furnishings show the influence of Acadians, the exiled French Canadians who resettled in Louisiana. (Acadian is the origin of the word Cajun.) Collections include silver and textiles. Pottery and bottles, paintings, candlesticks, and cookware are in daily use.

French doors and casements open the house to breezes from the galerie.

Attention was lavished on even small details of Creole life—for example, the arrangement of cups and saucers on the mantel. Doing research, they’d come upon a photograph and several separate mentions of “five china tea and coffee cups and saucers à la Française.” They know that Dr. John Sibley, a surgeon’s assistant in the Revolutionary War who became Indian Agent of the New Orleans Territory in 1805, wrote about a glass globe “open at the top with two golden carps inside” on a visit to New Orleans. Later they found a book about a French artist that showed a similar globe. Pat points to a globe near her living-room window; it has two golden carp. “That’s the kind of detail we go into,” she says.

Jack explains that French colonial houses did not have hallways; rooms were arranged en suite (in succession). For privacy, family members and guests could use exterior galeries to move from room to room. The interior today is painted in original colors revealed by scraping through layers of paint. The living room has mellow green walls over a light melon color in the dado. Grays and blues are used in the dining room and two bedrooms. Most of the paints were custom-mixed.

The Holdens bought this house in 1975, when preservation craftspeople and restoration materials were in short supply. The couple frequented flea markets and salvage yards owned by demolition companies, looking for such things as old window glass. Pat says they used an archaeological approach in their restoration, building an accurate picture of the house’s original construction and subsequent alterations. “If you examine the house very carefully,” she says, “it will reveal its secrets.”

Before the move, the house had a double-pitch gable end roof with the break in pitch near the apex. During reconstruction, they examined the truss, large purlin, and nail holes—and realized the original roof had been hipped. Early 19th-century roofs were covered with cypress bark, a durable material that was readily available. Small spaces were left between shingles, which allowed heat to escape from the attic; when it rained, the wood would swell, preventing water seepage. Jack had difficulty locating replacement roofing; he went as far as Oregon and Canada to find thin-cut shingles.

Underneath the plaster walls is bousillage, a mix of clay and grass (or Spanish moss) used as infill between timbers, a common housebuilding technique in the French colonies.

“You can see light coming through the roof,” he says. “The attic was done with as much care as the living room; we wanted it to show the construction.”

Because they could find no one who knew how to plaster the bousillage walls, Jack did the work himself. He found a plastering adhesive that allowed him to plaster over the existing wall. “We didn’t want to strip it clean,” Pat explains. “A hundred years from now, if someone wants to dig in, they can see all the layers.” Electrical conduit was hidden in trenches in the walls.

The batten shutters, original to the house, were found in the attic. “We went to each window to see if it matched,” Jack says, explaining that each hook had left a particular mark or groove on the trim and shutter. The sash was missing when they bought the doomed house. With careful research and examination of the jambs and original hardware, they were able to discern that the windows had been single large casements that opened inward, a style common in France but unusual in Louisiana. A set of French doors found in a pile of debris became their template for replacements.

The Holdens make reference to the architectural concept of tout ensemble—things taken all together, in context, as one entity. Their assemblage, by staying true to colonial architecture and landscape, preserves a time and place, revealing a French culture modified by local climate, terrain, and materials. Jack says every bit—from the architecture to the furniture to the details—works together. Small but significant motifs repeat—the lozenge or diamond form, for example, that’s evident on an old armoire, on a mantel, and in the garden. The Creole culture is reflected when tiny imported pink roses vine across a rustic cypress fence, and when refined French antiques sit beside Louisiana-made pieces. Tout ensemble, c’est tres jolie.