The house tucked on the western slope of Queen Anne Hill in Seattle looks very much as it did in 1913—thanks to the efforts of current homeowner Viki Sherborne. In fact, the semi-bungalow had been divided into four apartments during the 1950s, when partition walls and kitchenettes were added. Its handsome exterior was buried under grey asphalt siding. Bathroom linen closets blocked the back windows, the dining room had become a rental bedroom, and plumbing and electricity service ran in a perilous circuit through the attic and down the siding.

Liberated from asphalt siding, the original shiplap was restored and painted. Paint colors are Benjamin Moore ‘Chestertown Buff’ and ‘Kendall Charcoal’. The enclosed sun-porch glows at dusk.

William Wright

Viki’s parents bought the house as an income property in 1969. She inherited it in 2003. “I think, unconsciously, I’d been preparing to bring back this house for decades,” Viki says. She was owner of an antiques business specializing in British Arts & Crafts. A Seattle Craftsman would focus her collections and provide a showcase. She wisely decided to proceed slowly. A lot of work needed to be done.

First Viki hired a contractor knowledgeable about restoring historic houses. He did a comprehensive inspection and drew up a 17-page “scope of work” that detailed all the initial, critical projects needed to stabilize the house: new furnace, new roof, attic insulation, copper plumbing, new electrical service and wiring, exterior siding removal, chimney repointing, seismic upgrades, and new front stairs and posts to replace rotted areas. The initial work took two years.

Paneled walls in the dining room are freshened with a color called ‘Filbert’. The oak pedestal table, ca. 1900, also belonged to the owner’s grandparents, who had a bungalow.

William Wright

Then Viki began putting the house back together. The original shiplap siding was stripped and repaired, and, along with the dormer shingles, painted in a period scheme. The back porch, enclosed since the 1950s, was reconfigured to hold a powder room and a light-filled breakfast room behind the kitchen. Inside, Viki repaired or replaced rotted window sash and sills (exterior sills had been sawn off for the asphalt siding). She rolled up her sleeves to do the woodwork refinishing herself, after contractors heat-stripped decades of green, pink, and white paint from it. “Mahogany was considered more prestigious than the local fir,” Viki explains, so she used a brown mahogany gel stain and top coat after pretreating with wood conditioner.

Most of the walls had to be stripped of wallpaper and earlier calcimine paint. Then the plaster was repaired and skim-coated. Wood floors were sanded (using a Festool dustless sanding system). A pleasant American oak stain was used in the kitchen, warm mahogany on stairs and landings.

Nothing was thrown away, and salvage was incorporated: vintage push-plates to cover deadbolt holes in doors, old wooden air-return grates repurposed to camouflage modern heat vents. Unneeded cabinet doors became attic access doors, and the old back door was stripped and rehung in the bathroom.

The interior palette echoes the paint colors Viki uncovered during restoration. The living room is a soft green, the study a pumpkin color. The handsome brick fireplace had been painted in the 1950s; Viki toned it down with a light nut-beige, which she repeated for the always-painted board-and-batten woodwork.

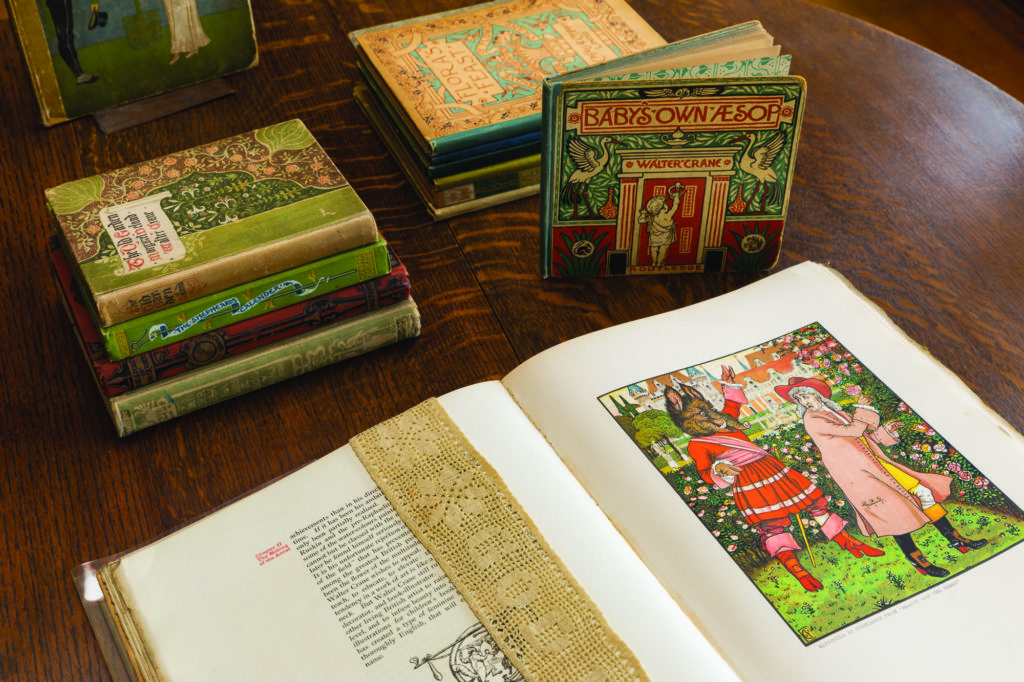

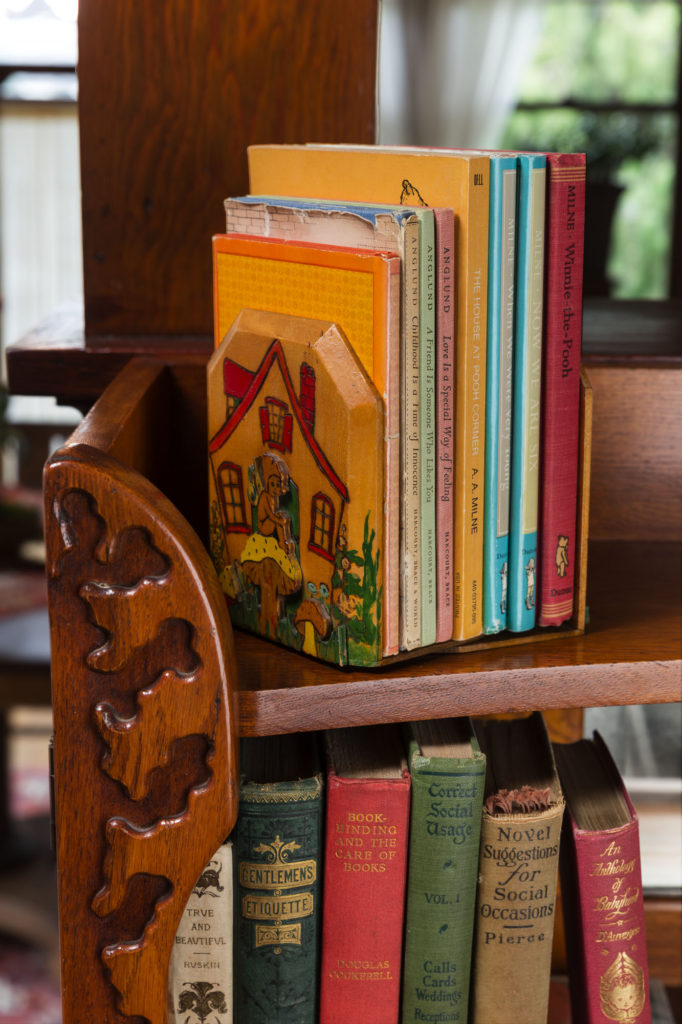

The main spaces flow from the living room to the study and the dining room beyond. Bookcases and desks hold collections of Arts & Crafts ceramics, family mementoes, and vintage books.

William Wright

The kitchen was a difficult project. Every surface—ceiling, walls, trim, cabinets—had been painted white. Original cabinets survived, but their insides were covered with peeling paper and dribbles of green paint. The stained fir was not painted originally, so Viki hired a contractor to strip all of it. Mahogany stain camouflages wear and marks. An unattractive 1950s sink was replaced by a Villeroy & Bosch model with integrated drain boards. The cabinet beneath it was custom-built with vintage fir doors to match existing cabinets. Viki was lucky enough to find a salvaged, narrow fir buffet from the same period, which fit along the wall opposite the sink. Seamlessly built in on a fir frame and with a crown moulding, it holds dinner service for 20. The enamel-top center worktable came up from the basement, and schoolhouse ceiling lights extend the early 20th-century look.

Fir cabinets in the kitchen were stripped of later paint. The little table, found in the basement, was fixed up for a workstation.

William Wright

Finally, after six more years, Viki could unpack her antiques. Bookcases and cabinets soon overflowed with her library, which includes children’s books extravagantly illustrated by Walter Crane, leather-bound tomes from the Roycroft community, hand-written cookbooks, and vintage books on etiquette. Her English and American pottery, plates, and tiles sit on plate rails and the mantel, and family mementoes are everywhere. The house, cozy yet spacious with 2,800 square feet, is warm and personal: the Arts & Crafts ideal.

The rich colors of enameled Ruskin Pottery stones and pins match the jewel tones in a ca. 1940 California tile-top table.

William Wright

Rare Ruskin

An English firm founded in 1898, the Ruskin Pottery took its name from the 19th-century art critic and social thinker John Ruskin. It was known for its brightly colored vases, bowls, and jewelry. But it was their high-fired specialty glazes that made Ruskin wares unique: misty soufflé glazes, crystal effects, lustre glazes that look like metallic finishes, and especially sang de boeuf and flambé glazes producing blood-red colors. Ruskin won a grand prize at the St. Louis International Exhibition in 1904. When the pottery studio closed in 1935, all of its formulas were deliberately destroyed so that the pottery could never be replicated.

Vintage Library

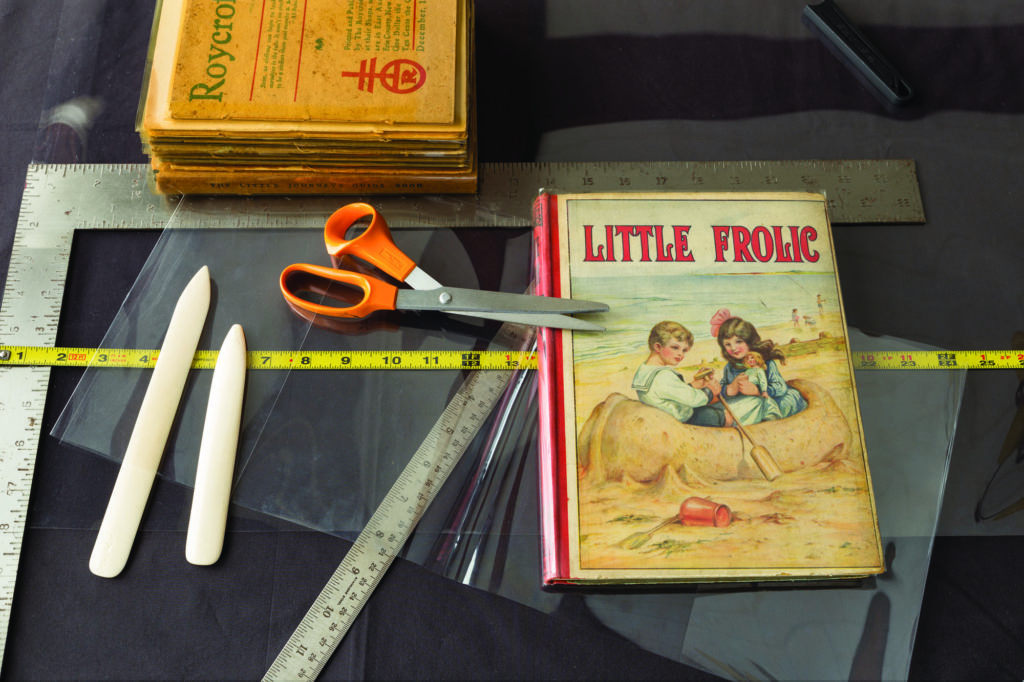

Viki Sherborne protects her vintage books with simple dust jackets she makes from DuraLar polyester film (widely available on rolls or in sheets).

> Measure the book top to bottom and add 1/8″ (or more if you want to fold over a durable “hem” at top and bottom edges).

> Measure the book from one edge of the cover around the spine to the opposite edge. Add half the width of the cover to each end for inside flaps.

> Transfer measurements to a clear DuraLar sheet using a L-square metal ruler and marking pen, then cut it out with sharp scissors or an X-acto knife.

> Use a bone or Teflon folder to create two folds to wrap the spine.

> Again using the bone folder, make two parallel folds each, at front and back book edges, to accommodate the thickness of the cover. (Neater, and it keeps the jacket from popping off.)

> Slip the transparent jacket around the book.