Although the 1754 home of the Rev. Joseph Bellamy was extensively added to in the 1760s, its high-style features were likely part of a facelift undertaken in the 1790s by Bellamy’s son David.

Kindra Clineff

A passionate voice of the Great Awakening, the Rev. Joseph Bellamy was a larger-than-life character in 18th-century Bethlehem, a fledgling town in rural Litchfield County, Connecticut. Both his prestige and his imposing physical presence—he stood over six feet tall, and weighed nearly 300 pounds—were reflected in the house in which he lived, taught, and wrote from 1754 until his death in 1790.

Now listed on the National Register of Historic Places and managed as a museum by the preservation organization Connecticut Landmarks, the house and its collection of Colonial-era antiques reflect the life of the privileged pastor. Just as present in the home are the trappings of another life—that of Miss Caroline Ferriday, the woman who is credited with saving not just the Bellamy home, but also the lives of dozens of women caught up in the horrors of a 20th-century war.

The Bellamy–Ferriday house has been described as one of the best surviving examples of Georgian architecture in Connecticut … but more than a century and a half of additions, remodels, and restorations make it a case study in architectural bewilderment. By most accounts the house began in 1754 as a two-storey gabled farmhouse, one room deep, with a front door centered on the long, east-facing side.

The original structure’s open first floor included a cased stair on the south gable end and a cooking hearth and oven on the opposite wall. The nearly 8’ ceilings in the house have been attributed to both Bellamy’s height and his standing as a pastor.

Drapes embroidered by Eliza Ferriday hang in the library, which the Ferridays painted in a green color matched to original paint found by scraping.

Kindra Clineff

Bellamy soon added on, more than doubling the size of the house with a two-and-a-half-storey addition set perpendicular to the original ridge line. Dates and details vary, but a National Park Service floorplan sketch showing the house as it might have been in 1760 includes rooms laid out roughly as they are today. The front door, in the addition and facing the green, opens to an entry hall with a curved staircase. A parlor is located to the left, a library to the north. Taking up the corner between library and hall, a sitting room completes the rectangular footprint. A door in the sitting room connects it to the original part of the house. The sketch shows the extant double-faced fireplace between library and front parlor, as well as a fireplace in the sitting room.

A remodeling ca. 1790, under the influence of Bellamy’s son David, gave the house its distinctive, late-Georgian features. The corners of the clapboard exterior were wrapped with stone-like quoins, the eaves highlighted with modillions, and the front entrance showcased with a two-storey entry pavilion featuring Ionic columns and a Palladian window. The embellishments may have been the work of William Sprats, a British soldier-turned-architect whose nearby work, including the Julius Deming house (1793), eight miles away in Litchfield, shares similar features.

the house remained in the Bellamy family, largely unchanged, until 1868, when it was sold to a succession of unrelated owners. By the end of the century, Victorian-era additions—including a porte-coche`re, bay windows, and a wraparound porch—overshadowed the house’s Georgian details.

The staircase sweeps past a window. The Ferridays filled the house with Colonial antiques, including the bedwarmers on the shelf.

Kindra Clineff

In 1912, the house was purchased by Henry McKeen Ferriday, a wealthy New Yorker, as a summer home for his wife, Eliza, and their nine-year-old daughter, Caroline. Not many years later, the two women would embark on a mission to restore the house as Bellamy had known it. They scoured the region for period furnishings and objects connected to the family, establishing their own museum dedicated to Bellamy in a playhouse on the property. Their acquisitions include the wooden box in which Bellamy kept his Bible. Carved in the bottom are his initials, along with “1740,” the year of his arrival in Bethlehem.

Eliza Ferriday hired the architect S. Edson Gage, a proponent of Colonial Revival taste, to adapt the house for 20th-century living, and to guide her in reappointing its interior to reflect its Colonial origins. Indoor plumbing was installed and a large kitchen, pantry, and servants’ quarters were added to the north end of the house. Victorian-era mantels were replaced with Colonial-style ones, and walls were repapered with vivid floral and avian designs reflective of Colonial taste. Gage left his own signature on the house with his renovations.

Mantels replaced during restoration match the style and quality of exterior elements.

Kindra Clineff

Eliza removed the Victorian porte-cochere—an appendage she reportedly found distasteful—but she was no architectural purist. She left intact a bay window that had been added to the sitting room, as well as a colonnaded porch that ran along the front wall of the original portion. For Caroline’s 16th birthday, Eliza had her daughter’s second-floor bedroom enlarged with a bay window overlooking the home’s formal parterre garden. In the library below, a similar bay and a break in the flooring that mirrors one in Caroline’s room suggests that the library was expanded at the same time—although a competing theory posits that the library was enlarged by the Bellamy family in 1767.

Caroline Ferriday’s room was decorated with a colorful wallpaper featuring birds and flowers. It is a vestige of the remodel directed by Colonial Revival architect Edson Gage, who left his mark in the curved corners appearing in rooms he reconfigured.

Kindra Clineff

In any case, the library bookshelves, still filled with more than a thousand volumes from Caroline’s collection, owe their sage-green color to the Ferridays’ painstaking efforts; it matches the bottom layer of paint and was assumed to have been the color chosen by Bellamy. We can’t be certain, though, because, for all his writings, Bellamy left no written account of his house.

Two Lives, One House

The original 1754 section is now the middle linking the 1760 front addition and a two-storey kitchen addition from the Ferridays’ time. A narrow barn was later attached.

Kindra Clineff

The lives of the Rev. Joseph Bellamy and the socialite Caroline Ferriday were separated by two centuries, but in this historic house in Bethlehem, Connecticut, their legacies are thoroughly entwined.

A protégé of the famous theologian Jonathan Edwards and a graduate—at age 16—of Yale College, Rev. Bellamy became the Congregational minister for the new town in 1740. A prolific writer and gifted orator, he preached throughout Connecticut and became a leader among “New Divinity” ministers, whose interpretation of Calvinist thought suggested that individuals played a role in their own salvation. He established a theology school in his home, counting a young Aaron Burr Jr. and Jonathan Edwards II among his pupils. Bellamy’s descendants include Francis Bellamy, author of the Pledge of Allegiance, and the actor Ralph Bellamy.

Caroline Ferriday.

Joseph Bellamy died in 1790. More than a century later, his home would fall into the hands of Eliza Ferriday and her daughter, Caroline. Caroline was an ardent admirer of Bellamy and is credited with restoring his home, but that was not her only calling.

The actress and heiress became a champion of the French Resistance in World War II, and was instrumental in gaining medical treatment in the U.S. for 35 women who had been subjected to horrific medical experiments in the Ravensbrück concentration camp. Her efforts earned her three medals from the French government, including the Legion of Honor. In 2016, Ferriday’s advocacy for the women of Ravensbrück was fictionalized in the novel Lilac Girls by Martha Hall Kelly. When Caroline died in 1990, she bequeathed this house, its contents largely intact, to Connecticut Landmarks.

Similar Wallpaper Today

Wallpapers remaining in the Bellamy–Ferriday House date to its Colonial Revival restoration, 1912–20s.

Vintage 1920s Collection #2D-121 from Bradbury & Bradbury is the same design as in the Bellamy–Ferriday bedroom! The company reports that their document wallpaper came from a collection of papers found in an Ohio barn. bradbury.com

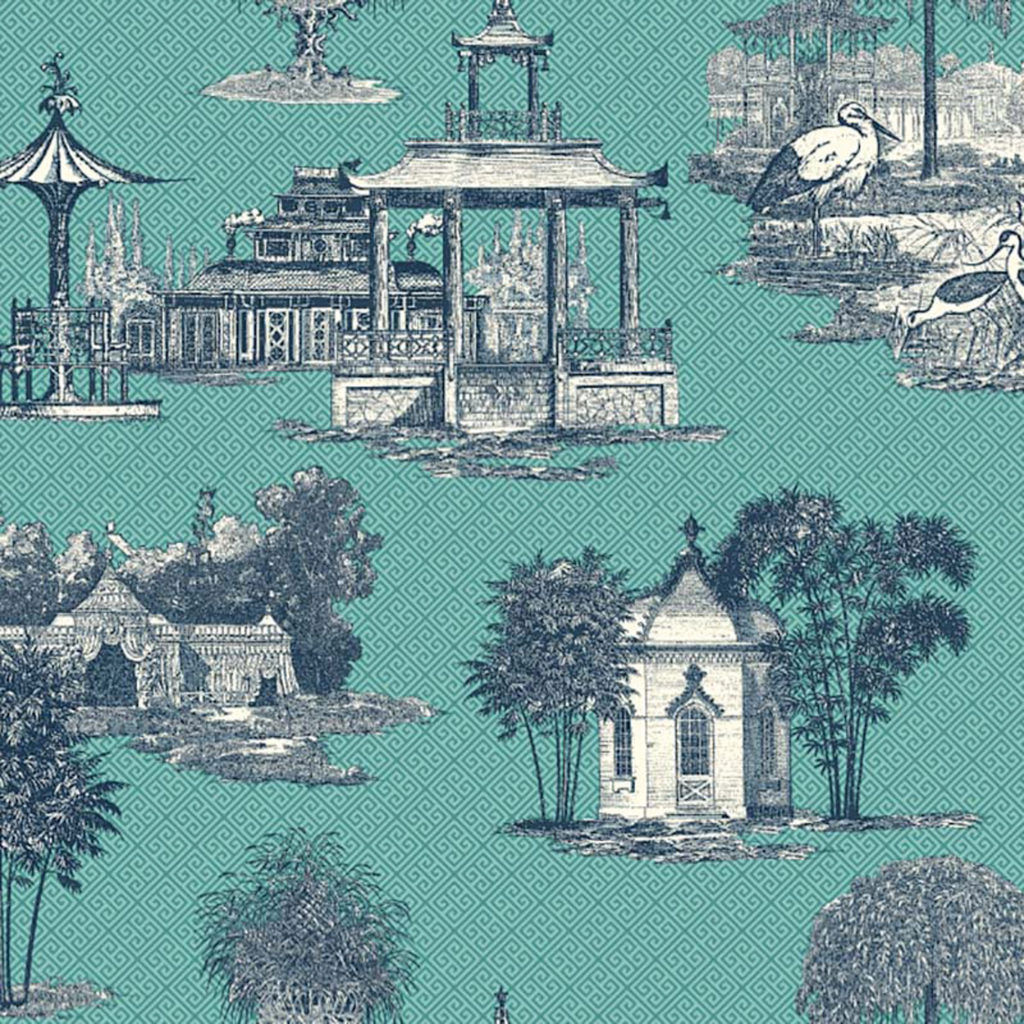

‘Mandarin Dream’ by York is a chinoiserie pattern, as is the toile paper that remains in Eliza Ferriday’s bedroom. yorkwall.com

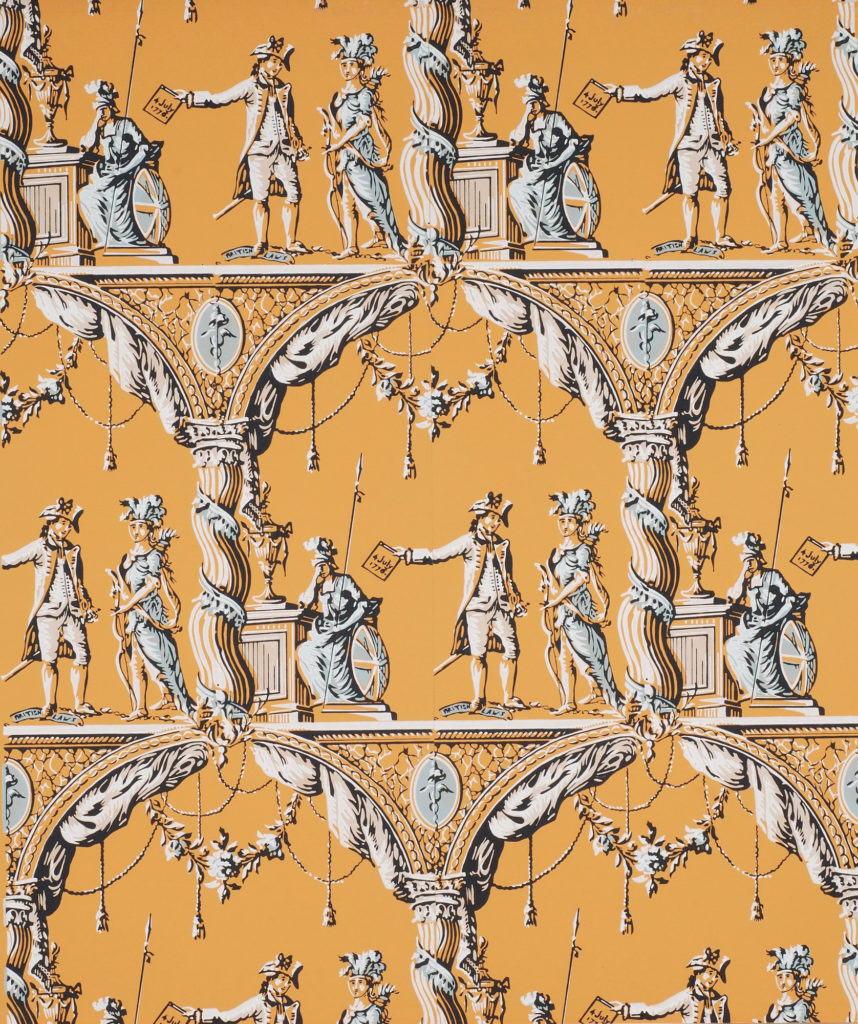

Pattern ‘1776’ from Adelphi Paper Hangings is an American pillar-and-arch paper, ca. 1790, which typically would have hung in a large hallway. Suitably allegorical, it shows France handing the Declaration of Independence to a weeping Britannia, with America represented by a Native American princess. (See also Adelphi’s ‘Butterfly Chintz’.) adelphipaperhangings.com

Eliza Ferriday’s bed was made in New York but customized with carved motifs of the South, a reference to her Louisiana roots.

Kindra Clineff

Learn more about historic wallpaper: oldhouseonline.com/interiors-and-decor/wallpaper-past-present-perfect