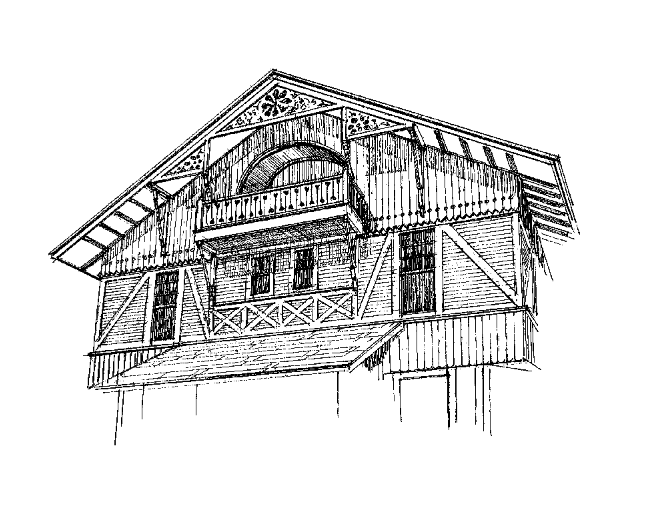

A Swiss Chalet bungalow.

Doug Keister

Widely considered to be rare in the United States, the Swiss Chalet deserves more credit for its influence on American Bungalows. Those picturesque wood details people tend to call “Craftsman” are actually chalet details: the wide, overhanging eaves, big brackets and knee braces, whimsical balustrades, exposed rafter tails, corbels, and banding.

Bungalows, too, are usually low and spreading, not more than a storey-and-a-half tall, with porches, sunrooms, pergolas and patios tying them to the outdoors. The Craftsman bungalow follows an informal aesthetic; it is a house without strong allusions to formal English or classical precedents.

Also like the chalet, indigenous materials are used for bungalows. An artistic use of river rock, clinker brick, quarried stone, shingles, and stucco is common. Arts & Crafts-era bungalows often exhibited exotic influences: not only Spanish or Moorish arches and tilework, or Japonesque orientalism, but also stick ornament in the manner of Swiss Chalets.

Bungalows came from India, sort of—variations of the word existed for hundreds of years before any bungalows showed up in England or the U.S. “Bunguloues,” temporary and quickly erected shelters, were houses for Englishmen built by native labor in India: long, low buildings with wide verandahs and deeply overhanging eaves. Around 1870, builders of newly fashionable English seacoast vacation houses referred to them as “bungalows,” to give them an exotic, rough-and-ready image.

But it was in California that the bungalow boom began. The climate was perfect for a rambling “natural” house with porches and patios. Los Angeles and upscale Pasadena, a resort town in the 1890s, were growing fast. An essential part of mass suburbanization was “an innovative, small, single-family, simple but artistic dwelling; inexpensive, easily built, yet at the same time attractive to the new middle-class buyer.” The California Bungalow (a term used by 1905) was soon a well-defined new style. Architects Greene and Greene in California called their millionaires’ chalets “bungalows.”

Nevertheless, it was the European chalet—which David Mathias, author of Greene & Greene Furniture, calls “a folk carpenter’s dream”—that influenced the Greenes. Indeed the essence of the chalet form shows up in the Pasadena houses: the uncomplicated but massive roof, the exposed structure—and wood details inside and out. Their “ultimate bungalows” were, of course, a higher architecture. While Gustav Stickley sang the praises of the bungalow (both California and Midwest types) in his magazine The Craftsman, his published house plans included several Swiss Chalets along with bungalows.

The word “lodge” is loosely defined. It might be the small cottage of a gate keeper; a country house or hotel occupied seasonally for fishing or skiing; a large inn in the mountains; or the main build-ing at a camp or resort. With northern European roots and nature-inspired architecture, picturesque and rooted to its place, the lodge is related to the chalet and the bungalow. It is often a timber-framed building or at least makes a show of structure and decoration in wood.

The most famous examples are the Great Camps of the Adirondacks and the National Park hotels, both dating to the late 19th century and built into the mid-20th century. Somewhat smaller family houses, usually sited on a lake or in the mountains, and featuring capacious porches and informal, woodsy interiors also were called lodges.

Swiss Chalet Bungalow (see top photo) “The Chalet Bungalow is easy to spot—it looks like a Swiss Chalet,” quips photographer and architectural historian Doug Keister. “Berkeley, California, is known more for political yak-yak than for yodeling, but that’s the location of this Swiss Chalet.”

A Chalet.

Rob Leanna

Swiss Chalets were a minor fad during the Victorian era (and related to the Stick Style), but chalet elements were common during the bungalow era of the 1910s. In this example, the first level is brick and stucco, with shingles above. More often the cladding is weatherboards.

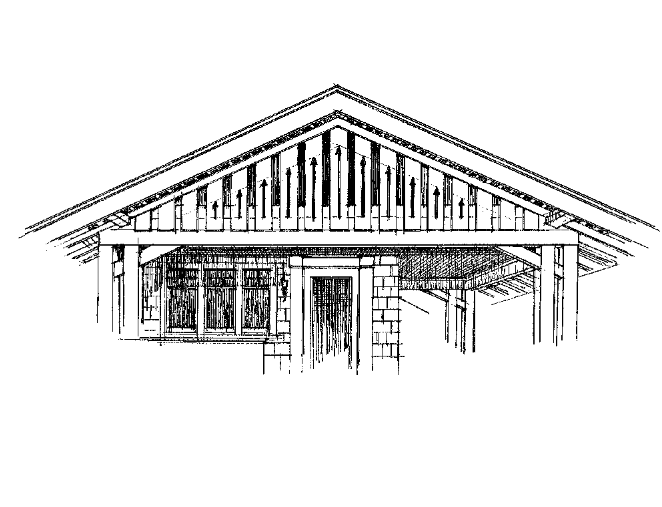

A lodge.

Rob Leanna

Lodge The rustic vacation retreats of Gilded Age barons, particularly those built in the mountains, often had Swiss or Nordic design elements. The illustration is based on Sagamore Lodge at Great Camp Sagamore (built 1895–97) in New York’s Adirondacks.

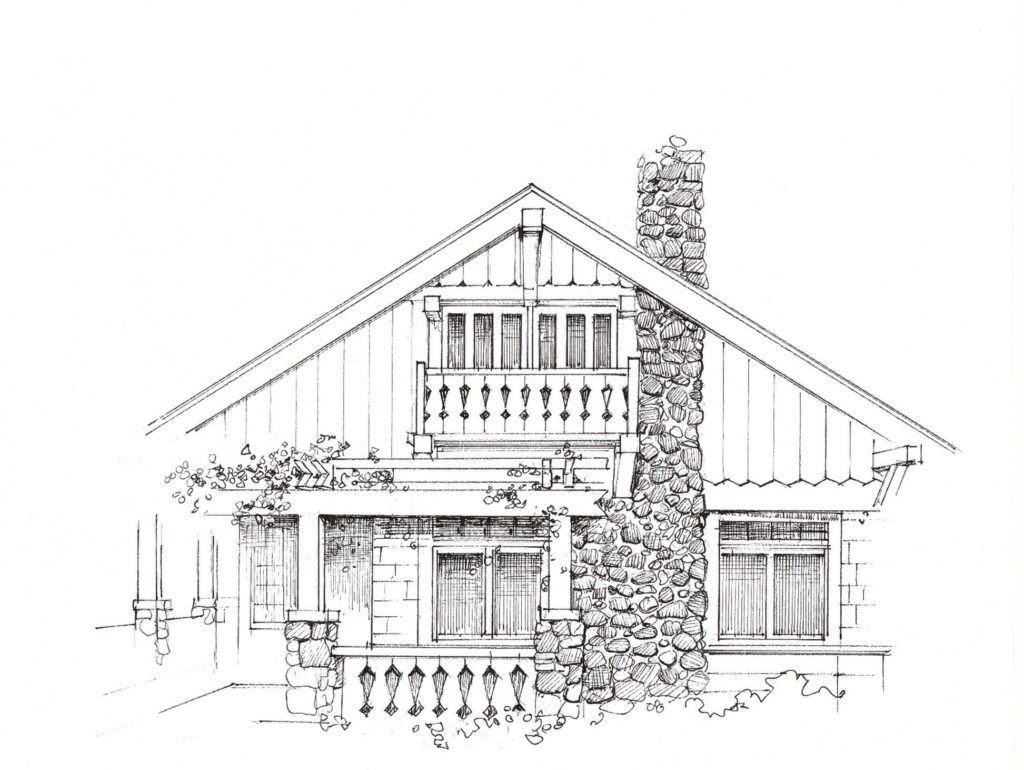

A bungalow.

Rob Leanna

Bungalow is an Anglicized Bengal (Indian) word that makes reference to the low-slung roof and indoor–outdoor porches of this house type. But many of the picturesque examples built in the U.S. have elements derived from chalet architecture.

A 1910 house in Spokane is a medieval take on the Swiss Chalet with its clipped gable and huge brackets under the balcony.

Doug Kiester

Chalet Hallmarks

• Alpine elements carry over to American houses, typically squarish and two and a half storeys. (Chalet Bungalows are one and a half storeys.)

• A pitched roof with front gable and wide eaves, usually with brackets or exposed rafter tails, is a defining element.

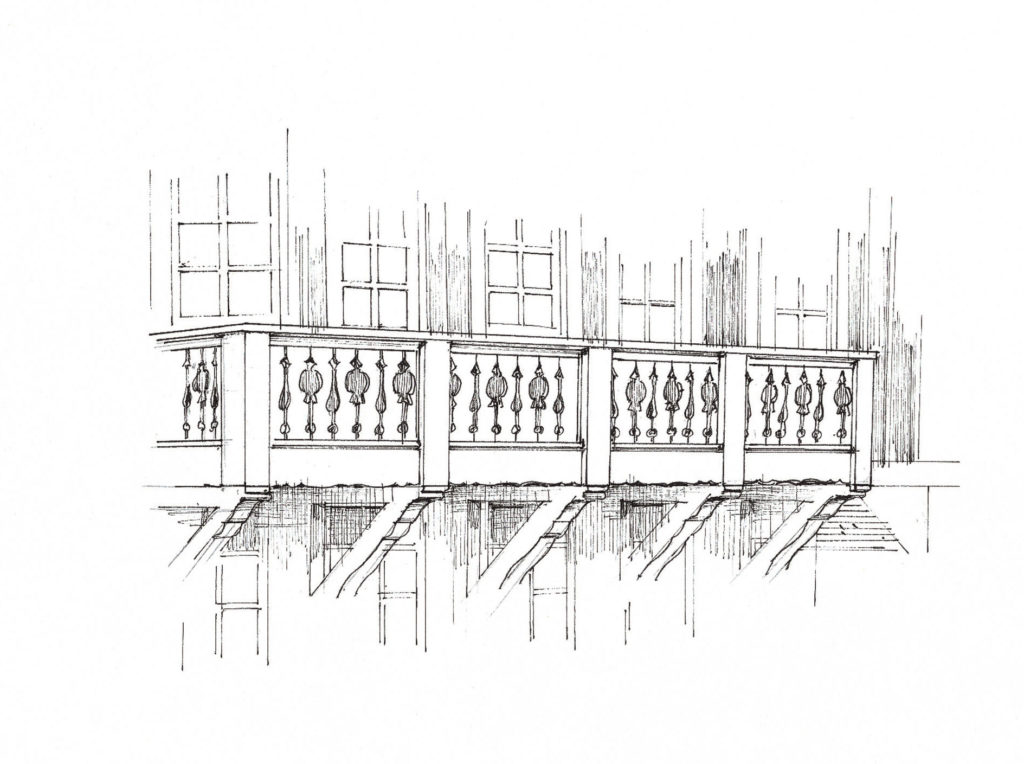

•Balconies and balustrades are identifying characteristics of the Swiss Chalet. In this country, the balustrade morphed into a second-storey porch, a balcony, or simply a decorative effect.

• Decorative work appears structural: gable ornament looks like a truss, brackets are oversized, and diagonal boards evoke framing timbers. Some American chalets are brick, stone, or stucco with wood above. Late Victorian chalets might have ornate carving and polychrome paint decoration.

• A galleried second level may look like the main floor, with the ground level secondary and sometimes of a different material. This mimics chalets in Germany and Switzerland, which were often tucked into hilly slopes with only a partial first floor.

Large, plain knee braces and decorative “half timber” trim boards have an Alpine appeal on this house with a broad, gabled roof and generous eave overhangs.

Doug Kiester

A Brief History of the Chalet

The chalet is an Alpine (German, Swiss, Austrian, etc.) dwelling built for snow-covered mountain areas, usually in wood and with overhanging eaves. Stucco and occasionally brick are also used, but wood trim remains prominent. The type is based on ancient vernacular forms.

• American Swiss architecture was promoted along with other Romantic styles by A.J. Downing in the mid-19th century. “Swiss” cottages were popular in 19th-century England. The style here had brief periods of popularity during the 1850s, later in the Victorian era (related to the Stick Style), and during the bungalow years of the early 20th century. It is particularly associated with Cincinnati and seaside resorts in New Jersey.

• Resort Over-scaled chalets with whimsical or bold details have long been built in ski areas and mountain resorts, for use as inns, restaurants, and rustic lodges. In the hotel industry today, “chalet” is used interchangeably with “cottage” or “bungalow.”

There’s no missing the point made by this chalet in Vallejo, Cal.: the gable roof, second-level porch, knee braces, and dark wood stain mimic Swiss models.

Doug Kiester

Chalet Vocabulary

• Bargeboard A flat or ornamented board attached along the projecting edge of a gable roof. It may be carved, incised, scroll-sawn, or cusped. Used on houses influenced by the Gothic, Chalet, and Tudor styles.

• Bracket The general term for a discrete projection that provides structural or visual support under

a roof cornice, balcony, etc.

• Corbel A stone or brick bracket that supports a cornice, arch, etc. Also a masonry projection that steps out, increasing in depth to support an overhanging member above.

• Fancy butt Describes ornamental cuts on the visible ends of wood shingles, such as round, fish-scale, diamond, arrow, and octagonal.

• half timbering Here it refers to a faux treatment of boards used decoratively over the facade, popular in Swiss- or German-influenced and Tudor Revival, and Arts & Crafts houses.

• Knee brace A diagonal support between vertical and horizontal members or a bracket that includes a diagonal support.

• Rafter tails The ends of roof support rafters are sometimes decoratively cut and left visible in Alpine, Nordic, and Arts & Crafts houses.

Gable, Verge & Truss

European chalets generally have only a scalloped bargeboard at the eaves, and exposed (sometimes carved) rafters or knee braces as gable details. In this country, fanciful, non-structural trusses, brackets, and gable ornaments were more common.

Balustrade & Balcony

Along with the roof, balconies and balustrades are the identifying characteristics of the Swiss Chalet. In the Alps, a wide gallery above the ground level was typical. In this country, the balustrade morphed into a second-storey porch, a balcony, or simply a decorative effect.