A cross gable with Palladian window above a large bay window anchors the rambling façade facing the entry courtyard. A long porch ties together the wings of the house and provides welcoming, gracious entry points into two ends of the house.

Photographs by Eric Piasecki

Architect Gil Schafer is renowned for his contemporary examples of Classical architecture. A penchant for traditional crown moldings, door and window casings, baseboards, staircases, and hardware is regularly evidenced in his work. Yet, he remains flexible in order to accommodate a structure’s sense of place. This Lake Placid home in the Adirondacks is a fine example of that vernacular sensitivity.

The homeowners grew up vacationing on the lake—a place with special meaning for the couple whose families had spent time on its banks for multiple generations. “They had [a feel for] the history of the place, and they wanted their new house to [be reminiscent] of the older houses they had known growing up,” explains Schafer. “That was always part of our design thinking from the get-go.”

Large glass sliding pocket doors provide easy flow from the kitchen out to this dining alcove at the western end of the long lakeside porch. Square columns and clapboard-clad piers frame the view of the lake and Whiteface Mountain and integrate the porch into the architecture of the façade. All of the seating furniture for the porch was made in Adirondack Style wicker and painted white to play off the dark color of the walls.

To gain that same appreciation, Schafer began by driving (and boating) around the region, looking at houses to study vernacular materials and forms. “In the Adirondacks, there’s the kind of log house that everyone is familiar with,” he says, “but there is also another tradition, which is a bit more tailored, of brown clapboard or shingled cottages with green shingled roofs and simple, tailored trim work.” That is what appealed to the clients. That was the starting point.

Secondly, the program considered how they wanted to live in the house. Schafer took inspiration from a previous home the clients had owned and loved; it featured a generous living room used for both dining and socializing. That room became central to the plans.

Also influencing the design was the clients’ fondness for formality, which was slightly at odds with the vernacular traditions. Striking a balance became an integral (and constant) part of the design process. Blending formal elements into a summer cottage-inspired program proved challenging, but may very well be the reason for the home’s success. “They were always looking for a certain formality, and I was always nervous it was going to be too formal for a relaxed summer house setting,” notes Schafer, adding that the end result is a house that can best be described as “Lake Placid vernacular with the picturesque quality of the Adirondack camps and some of the more tailored Classical characteristics of the Colonial Revival period.”

The entry hall encloses the house’s main staircase and opens into its central public room, the great room

Built into a hillside, the house has two principal façades. The motor court entry side presents as a two-story structure, and features a long porch with Greek Doric columns and a Serlian window in the cross gable, which is meant to anchor the center of the composition. “The combination of the long porch that ties together the front and side entrances, and the Serlian window . . . is a Classical kind of gesture,” explains Schafer, noting that the off-center entry is also in keeping with that tradition.

Out back, where all three stories are in evidence, a second porch with clap-dressed corner piers runs the length of the house and overlooks the lake. “We wanted that projecting porch to have a certain heft to it,” says Schafer. “That’s why the corners are made out of the same clapboard [as the house]; the piers are almost L-shape, and . . . it gets architecturally lighter in between those corners but [they] have the same solidity and strength as the rest of the house.” The mushroom gray, wide-wood horizontal planks comprising the bottom walls create a kind of plinth for the porch, and are meant to give the impression of a stone base.

Full height inset paneling in the hall is given a more vernacular character by butt-jointed vertical boards in the panels.

Inside, the inset paneled entry foyer demonstrates, once again, Schafer’s ability to harmonize seemingly conflicting styles. The panels are made up of boards whose seams will become more visible as the wood ages—something seen in late 19th- to early 20th-century houses. Adding to the allure is the staircase with simple spindle balusters of mahogany and detailed brackets. “We love to give those [brackets] different shapes and articulation depending on how dressed up or dressed down the house is. This one has an elegant shape that’s not overly ornate,” says Schafer, who harbors an affection for staircases, believing they tell the story of a house in terms of the period to which it points.

The lofty living room takes center stage and measures nearly 40 feet long. At its heart is a fireplace with Lake Placid granite stone surround—the same stone used for the chimneys. “I always try to use a stone that is indigenous because when you don’t, it looks out of place,” notes Schafer. The mantel, with its simple brackets and molding, is yet another example of Schafer’s balancing act. It’s large enough to hold its own without being overly dressy.

The long porch facing the lake is punctuated by simpler square piers and a delicate railing of cottage style windows on this elevation further reinforce a more vernacular attitude to the house’s lakeside façade.

The sense of light was a key consideration in the main living space, hence the transoms above the French doors opening to the porch. In the doorways between the front hall and the living room, Schafer wanted the openings to be as tall as possible to create an open, relaxed feel while also bringing down their height so as not to feel too grand. Typically, when designing a living room, Schafer orients the house to capture views and southern light. In this case, the lake view is on the north side, which cuts the light, as does the back porch. To compensate, he added a large bay window to collect sunlight from the edge of the south-facing porch. And, on the north side, he used as much glass as possible.

The kitchen is appreciated for its granite fireplace, full-height bead board walls, beamed ceiling, large island, built-in china hutch, 10-foot-long farm table, bay window with banquette, and antique oak flooring, which is found throughout the house. Simple surface-mounted milk-glass lighting fixtures are found in each of the beam coffers, and six-foot-wide pocket French doors open to a dining porch, where occupants enjoy a view of Whiteface Mountain.

Upstairs, all the floors are painted—a vernacular gesture toward a summer house—to make it “a little less serious.” And, Schafer ran the hallway that connects one end of the house to the other on the uphill side, away from the view, thereby locating the bedrooms on the view side. There are seven bedrooms in total, two of which are on the lower level, which also houses a gym, laundry, and large playroom with built-in bed alcoves meant to accommodate the family’s three teenage girls and their friends.

Schafer is careful to note the back stair, with its tall arched window and polychromatic cascading runner. “I knew that it would be the staircase that the husband and wife would use to go upstairs every day, so I didn’t want it to feel like a narrow service stair,” he explains. “We gave it that big window to lend a little more elegance. . . . [Today], back stairs become as important as front stairs, and are used just as much. So we try to make them into something special. There’s still a hierarchy, but they are not forgotten . . .”

Though the homeowners appreciate formal architecture, they are very light-hearted and cheerful people—a quality that informed many of the color and fabric choices. “A house should be a reflection of its owners and the life they live,” says Schafer. “This house was designed in that spirit.”

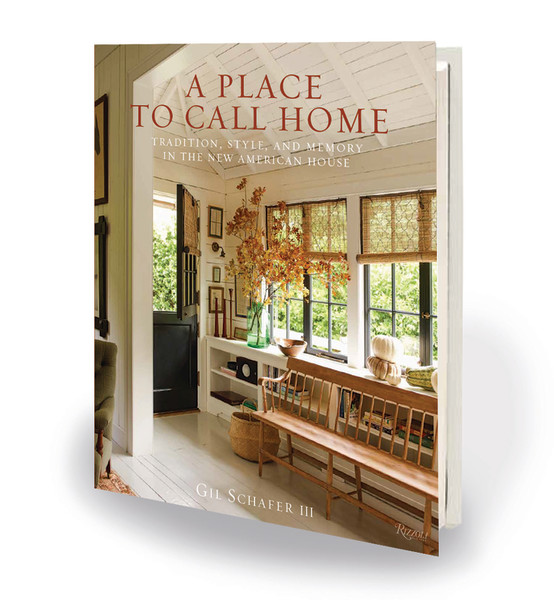

A Place to Call Home: Tradition, Style, and Memory in the New American House Published by Rizzoli.

A Place To Call Home is a follow-up book to The Great American House: Tradition for the Way We Live Now, published in 2012. Since that book’s release, Schafer has worked in many locations beyond the Northeast and Southeast, which were its focus. “My work is very influenced by the way I grew up,” says Schafer. “And I grew up living in a few different places—in the Northeast, Midwest, California, Bahamas . . . I’ve grown up thinking about what makes each place unique, and what gives each place its character—that has made me interested in . . . designing houses that connect with where they are, that have a sense of place and are true to that place.” The book demonstrates the ways in which geographical and lifestyle diversity affect architecture and design choices. The reader takes a journey that traverses the country in all four cardinal directions. “I try to listen to what each place and each house has to say and to design accordingly.”