In 1798, merchants lived above these stores on lower King Street, still a bustling area.

Alexandria, Virginia, is a dense and walkable little city on the Potomac River, just south of Washington, D.C. Founded in 1749, when Alexandria was a thriving tobacco port in a British colony, it is renowned as George Washington’s hometown (his Mount Vernon estate is located just a few miles south of the heart of the city), and it still harbors a varied array of pre-Revolutionary War houses.

However, even experts have to look closely to spot the genuine articles. Time and an early 20th-century penchant for “colonialization” can make it hard to sort out the centuries here—but it’s always worth the effort.

That’s because, despite its mercantile past, Alexandria has always been, first and foremost, a city of houses. In fact, its Old and Historic District was among the first of its ilk to gain local, state, and federal recognition for its Colonial buildings. And, given the attractions its celebrated Old Town streets hold for tourists, politicians, and history buffs, you never know what—or whom—you may bump into while you’re house-gazing.

Alexandria’s visitors’ center, the Ramsay House, is one of its premier colonial treasures. The gambrel-roofed wooden building started life on an unknown site some distance away from its present corner location in the heart of Old Town. It was built circa 1724 as the residence of one of Alexandria’s founders and moved to its current site around 1748. It was reconstructed in 1956, incorporating the remains of the original house and using archeological and photographic documentation to recreate an authentic picture of a prosperous colonial Virginia home. Its high stone-and-brick basement and massive-but-shapely exterior chimney are hallmarks of its type.

Attenuated columns add elegance to the entry porch of this 1786 house on Fairfax Street.

Nearby, the Carlyle House, now a historic house museum, offers yet another—and much grander—version of colonial prosperity. The stately Georgian Palladian stone mansion was erected in 1751-53 by John Carlyle, a wealthy Scottish immigrant, within sight of his busy riverfront warehouses. The Carlyle House was perhaps Virginia’s most impressive urban home outside of the colonial buildings in Williamsburg, and the smooth, ashlar stonework is unique in Alexandria. A symmetrical façade anchored by an impressive projecting pavilion—with stone quoins at the corners of the main block and pavilion, and surrounding a gracefully arched entrance—gives the big house a stylish dignity that reflects its Scottish heritage.

The Carlyle House’s flanking outbuildings have long since vanished—along with its other outbuildings—probably in the mid-19th century, when the house was obscured by the erection of Alexandria’s most up-to-date hotel in its front yard. The hotel was demolished, and the house was restored in 1976. Visitors, who are often surprised by the sparsely planted front grounds (representative of 18th-century landscaping practices), are charmed by the lushly terraced rear garden.

Economical Spaces

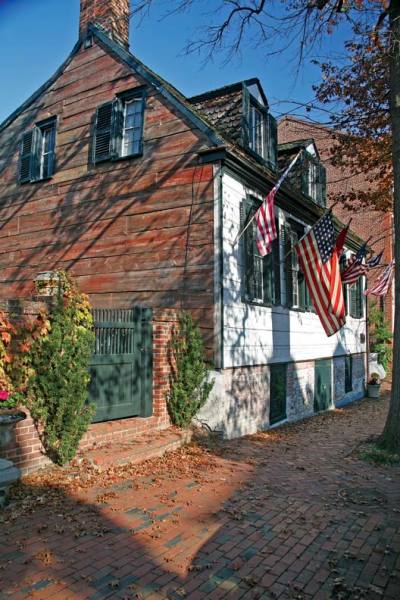

The size and isolation of the Carlyle House were far from the norm for Colonial buildings in Alexandria. Much more common was the simple three-bay row house, similar to those in other old East Coast cities like New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. This economical use of land was exactly what the city’s early planners had in mind when they issued the 1751 regulation requiring that houses be built all the way to the street. Brick sidewalks now occupy part of the old cobblestone street frontage, but the effect is just what was intended. Only a few short stretches of the cobblestone streets still survive (fortunately, for the safety of drivers and pedestrians!).

Alexandria’s Old Town is filled with a mix of large brick houses built for businessmen and many small frame workers’ houses—all now restored and prized by preservationists. The old brick sidewalks are typical of the area.

This early law is what gives Old Town its sense of architectural order, with block after block of unbroken rows of narrow houses punctuated by the occasional cobblestone alley or the even more rare—and highly coveted—side garden on an adjoining lot.

The brick party wall—i.e., one wall shared by two houses—was commonplace in Alexandria construction for many reasons. First, it allowed tight development, with no wasted space between houses. It also made for sturdy construction, since the framing of each house was actually built into, as opposed to merely abutting, the walls of its neighbors. And, most important, it provided a relatively fireproof separation between houses.

In fact, it would be hard to overemphasize the importance of brick as a construction material in 18th-century Alexandria. There are, of course, frame houses in Old Town. However, in such a densely built area, fire was (and still is) a major concern, and wooden houses are more vulnerable to fire than masonry ones.

Even brick houses are not immune to flames, however. Captains’ Row, a block of pre-Revolutionary Alexandria houses built on filled land near the waterfront, is evidence of that sad fact. A wild, wind-driven conflagration in the spring of 1827 burned or severely damaged the line of Colonial houses that had sheltered seagoing merchants. After the fire, some were reconstructed in their original Georgian form, while others were replaced with more up-to-date Federal-style residences. Subsequent owners, eager to establish or enhance their homes’ venerability in the Colonial Revival period, sometimes “earlied up” their properties by adding Georgian-style details, especially dormers and fancy entrances, and/or removing evidence of later construction.

One of Alexandria’s earliest houses, built around 1775, awaits paint on likely original wide side boards.

Just as masonry buildings have been significant in Alexandria’s architectural past and present, slate roofs are also important features, for their weather- and fire-resistance as well as their stylish appearance. Slate was an especially appropriate roofing choice because Virginia is a slate-producing area.

Georgian Statements

The Georgian town houses of Alexandria are soothingly consistent in form. They are narrow buildings, generally three bays in width, with a side-hall floor plan that places the front door at an outer edge of the building’s front wall and the interior staircase along a party or exterior wall. (Very occasionally, the entrance is on the side of the house.) They are two, two and a half, or even three stories in height. Rooflines slope toward the front of the lot, so almost no gable ends face the street.

There is almost always a rear service wing that is slightly lower than the main block. The wing has a side-sloping shed roof that might join the wing of the neighboring house at the top of the slope, thus making a single gable end that faces the rear of the lot.

The curved stone steps and platform, accented with an an ornate cast-iron railing, are distinguised mid-19th-century additions to this Prince Street house.

This practice of shed-roofed rear wings led to an Alexandria oddity called the Flounder House. Owners, who were required to start construction within a specific time period after purchasing their lots, often built the wing first, in the appropriate spot at the rear of the lot, intending to add the main block of the house later. Sometimes, however, the main block never materialized. That led to a few non-conforming half-houses with side-sloping roofs and (whoops!) front yards, despite the setback prohibition.

One of the less visible charms of Old Town is its Colonial gardens, which are usually, though not always, behind the house, enclosed by the close-set buildings, garden walls, and fences. These are disappearing as owners take advantage of the deep rear yards to enlarge their residences.

The survival of Alexandria’s architectural heritage has been due largely to the fact that it never experienced the rapid growth spurts that decimated historic areas of other, more commerce- and industry-oriented cities. Soon eclipsed as a port by the more favorably situated Georgetown, Alexandria seemed to slumber through the 19th century and into the 20th, until house-hunting Depression-era New Dealers brought it back to life. Since then, its charm has only blossomed.