Photo: Jonathan Wallen.

The grand entrance hall is a Colonial Revival standard. In interior design, Colonial Revival surpassed even the French Louis styles prior to the First World War. For most people, it was an affectation more than it was historically accurate; only the wealthy clients of decorators got actual period rooms. The familiar stage-set Colonial interior appeared early on: the rocker, the Windsor chair, the dressing table set with an antique shaving glass.

But even die-hard Colonial Revivalists were not that interested in accuracy; after all, they were borrowing motifs from a narrow field of the richest colonial citizens. The Revival imitated only fine houses; rustic objects may have been placed as icons, but in general, that which was poor, primitive, or dirty about real colonial life was ignored.

At the turn of the century, rooms with well-placed antiques were stripped of clutter, and simplified by the use of one paint color and one fabric pattern. The very Victorian center table was pushed into a corner. Chippendale-style chairs and a neoclassical mirror were brought in. Wallpaper was lighter in color: florals on pale backgrounds and stripes were most popular. Ceilings were usually left unornamented.

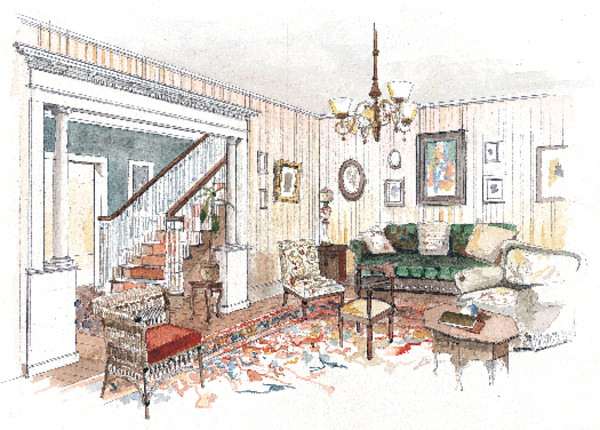

Neo-Georgian woodwork painted high gloss white: a Colonial Revival room. (Illustration: Rob Leanna)

The ca. 1900 parlor decoration would have been so considered, even though only the chair in the center is actually a revival piece. Striped wallpaper was used in both “colonial” and French rooms. Gone are Victorian “art units”; instead pictures hung directly on walls are arranged symmetrically. Note the 1870s side chair reupholstered in chintz. American orientals cover most of the floors. NOTE: Interior views are after actual period photographs annotated by William Seale.

Paintings atop busy wallpaper, different upholstery fabrics, and the cluttered curios indicate lingering Victorian taste. But the paper’s light background is typical of colonial interiors.

High wainscoting, which might have been polished oak in a similar house, is here painted colonial white. The stair, Federal in its elliptical curve, is nevertheless given early 18th century balusters, probably copied from a New England restoration. A wrought-iron lantern on the newel imitates a cresset. The funniest piece is the mahogany settle. Its Chippendale feet and arms and giant pedimented back illustrate the tendency of revivals to exaggerate appealing features of the original to the point of distortion.

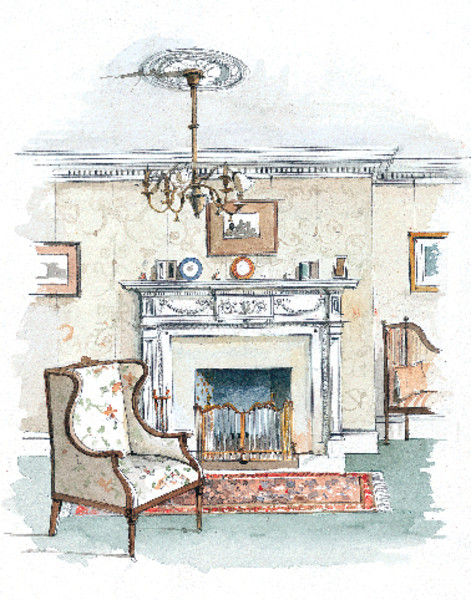

English Sheraton-inspired reproduction furniture fills this ca. 1900 attempt at a true period room. (Illustration: Rob Leanna)

Most of the major furniture styles of the 18th and early 19th centuries—Chippendale, Queen Anne, William and May, Sheraton, Hepplewhite, and American Empire—were revived by 1900.

Some pieces were fairly accurate reproductions, although no Revival furniture maker was above mixing the best of different styles. A Pilgrim substyle appeared in the 1890s and was still popular for informal use into the 1930s.

In any given room, furniture was rarely all of a style or era. Eastlake pieces were still popular. Grand Rapids furniture of the Golden Oak period was stripped of applied ornament and painted with white enamel. The very popular Arts and Crafts style was not to be ignored; in fact, it was the most popular style between 1893 and 1910.

By the end of the 1890s, however, the rich were back to historical revival styles. There was a revival of 18th century Queen Anne furniture, chosen by the middle class as a more livable alternative to the formal revivals (including the Greek-derived American Empire style) yet not so informal as Arts and Crafts. Queen Anne furniture in black walnut, oak, or mahogany included panels of woven cane and loose cushions. Mahogany was thought to look best with white woodwork, especially in bedrooms.

Historian John Burrows has suggested the name Old Colonies Style for the nostalgic, transitional houses of the early revival, and particularly for their interiors, which often mixed iconographic “colonial” items such as a Windsor chair or spinning wheel with English art-movement wallpaper by William Morris and the odd piece of Arts and Crafts furniture.

This period marked the end of the tripartite division of walls into dado, fill, and frieze. Now there might be a dado or a frieze but rarely both. Raised-panel or other wainscot was still used in halls, dining rooms, and libraries. Large pictures still hung on exposed ropes from hooks on the picture rail, but smaller frames were now fastened invisibly to the wall.

In a city house of the 1890s. (Illustration: Rob Leanna)

For nearly 75 years, woodwork had been dark and massive. In the early days of the revival, raised-panel woodwork was often varnished. Houses built in the Colonial Revival style had simpler woodwork, often painted in a glossy off-white know as colonial ivory; more accurate soft greys came even later.

The white woodwork craze can be traced to the White City at the Chicago Fair in 1893, where it was decreed by the planners of the City Beautiful that all buildings would be white, inside and out. Georgian-era buildings, of course, had been painted in greys and grey greens, even blue and gold, but the public association between classical and white had been made.

Primary and secondary hues were replacing late-Victorian tertiaries as early as 1890. Contrast schemes were used throughout the 19th century, even in the last decade. But analogous and occasionally even monochromatic schemes were also advised in the last quarter.

With the lighter woodwork, pastels came back for the first time since the early 1800s. Wallpaper patterns tended to the floral, similar to designs of the 1850s, their realistic representations of lace, medallions, statuary, and metalwork antithetical to the Art Movement. Even embossed Lincrusta-Walton wallcovering, for decades finished in deep browns and maroons, was shown in ivory and gold at the Fair. Federal Revival houses dressed in delicate ceiling medallions, classical cornices, and Adam style mantels would have walls painted in light blues or apricots. Federal era reproduction wallpapers were widely available.

Ivory paint on neo-Colonial woodwork is a convention of colonial interiors. This house is by Stanford White. (Photo: Jonathan Wallen)

Polished wood floors and scatter rugs have come to be associated with colonial decorating, but they are actually Colonial Revival. Large carpets were sent out to be cut up and bound as rugs; reproduction oriental carpets were common. “The chintz decorator,” Elsie de Wolfe, mad it clear in her best-selling The House in Good Taste (1910) that chintz was particularly appropriate for Colonial Revival interiors. (Chintz is a glazed cotton, usually with at least five colors and frequently in large floral patterns.) The lightweight and affordable fabric was a reminder of those 18th-century days when curtains were functional and an accent rather than an overwhelming presence.

Chintz was often the only pattern used in a given room. Light colors were recommended for bedrooms; the black chintzes suitable for public rooms were reproductions of 1830s fabrics. Elsie de Wolfe was big on valances, 10 to 12 inches deep or of a length equal to one full repeat of the pattern. Ruffles were for summer cottages and bedrooms. Fitted valances in chintz or brocade, she said, were more suitable in the drawing room. By the teens, interior light had changed with electricity; any dark corners remaining were swept clean and colors got brighter. Even the middle class was adopting bareness and restraint.