With a solid project team in place, including designer Richard Rossi and contractor David Brown, Decker was able to create the perfect new old house for a young couple and their children.

Gordon Beall

Abandoned houses have a curious allure. When we walk or drive past them, we always steal a quick look. But why should this be so? They lack everything we prize in a home. No warmth or light emanates from behind their broken windowpanes; no pride of place is evidenced in the shadowy, overgrown yards; and no happy signs of life can be discerned within.

Perhaps it is because an abandoned house calls to mind old movies, ghost stories, and gothic romance novels. Or it may cause us to consider what the house was like when newly built and elicit a desire to return the house to its former glory. And we cannot help but imagine ourselves and our families living there, restoring the house and refilling it with life. It’s likely all of these reasons played a part when Anne Y. Decker, AIA, was approached by a young couple who had acquired just such a place in Somerset, Maryland.

Vacant for more than 20 years following a fire, the circa 1891 Queen Anne—the oldest house in town—caught the couple’s eye soon after they began renting another house nearby. Others had shown interest in purchasing the property through the years—particularly builders attracted not by the old house itself but by the possibility of subdividing the one-plus-acre lot. But because the house is on the National Register of Historic Places, any new owner would be required to preserve it. “That dissuaded a lot of builders,” says Decker, a principal of Rill & Decker Architects, PC, in Bethesda, Maryland. “It took an unusual client to buy this property, really. You had to sign a waiver just to enter into the house. Floors were missing, the back of the house was missing, and, in fact, it was called ‘the haunted house.'”

A combination living room and dining room, the great room retains a cozy and approachable feel despite its large proportions. “The coffered ceiling adds interest while bringing down the scale of the high ceiling,” Decker says. The Rumford fireplace further domesticates the expansive dimensions of the room and is a design well suited to a large living space.

A combination living room and dining room, the great room retains a cozy and approachable feel despite its large proportions. “The coffered ceiling adds interest while bringing down the scale of the high ceiling,” Decker says.

Gordon Beall

The New Speaks to the Old

Decker’s task was to restore the original structure and also create a new addition to accommodate the owners and their two kids. To be successful, the addition and restoration would have to address the local historic commission’s regulations and respond to both the Queen Anne style as well as the clients’ own stylistic sensibilities.

Although one might expect that a new addition would blend seamlessly into the old, disguising where the original part leaves off and the new part begins, this is precisely what the local historic preservation commission forbids. As Decker explains, “There had to be a clear delineation or distinction of what was old and what was new. So, for example, you could use very similar siding, but not replicate the siding.” The regulations also required that any addition not be fully visible from the street, so Decker devised a plan to add to the rear of the house, extending out from where the original kitchen—gutted by the fire—once stood.

As for the owners’ tastes, “They are old-house lovers and are very respectful of the house’s style and integrity,” Decker says. “And yet they also wanted a little bit of a cleaner line in the addition. So what we did, to use in a farmhouse vocabulary—as far as the massing and the general feel of the house—was to have the new speak to the old.”

The only thing you really see from the street is the jut out of the den,” Decker says. “We tried to not take away from the prominence of the old house.” With a solid project team in place, including designer Richard Rossi and contractor David Brown, Decker was able to create the perfect new old house for a young couple and their children.

To create this dialog, Decker and designer Richard Rossi took the language of the historical home and interpreted it in a more contemporary, but respectful, way. Architectural elements such as the turret in the front of the house, a gable bay, and porches “would be recalled in the new addition but not repeated verbatim,” Decker says. “We wanted to keep the same vocabulary going, but add a little bit of a twist.” This architectural translation can be seen clearly in the way the roofline of the addition communicates with that of the old house. Decker broke the addition up into “bite-sized pieces,” and “housed each individual space under its own roofline,” she says. “When you view the roofline, these bite-sized pieces speak to the same proportions seen in the original house.”

Historic Language and Punctuation

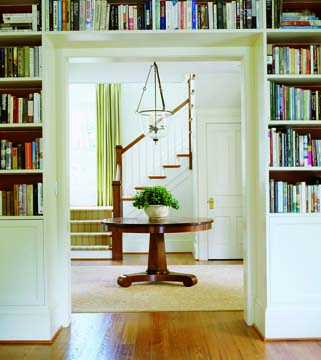

Because of the size of the addition—which would encompass a stair hall, den, living room and dining room, and a kitchen downstairs and a master suite upstairs—and because this addition needed to be somewhat distinct from the old house, the challenge was to marry the halves together. The solution was to create a one-and-a-half story entry foyer between the two. “We wanted the addition to defer to the old house, so we created a hyphen, or link, separating the old from the new: a transition space from old to new.” This link is further reinforced by the continuation of the house’s stone foundation, which is higher at the new entry foyer and then lowers again, thus establishing a subtle connection between the two structures.

Entering the stair hall from the new foyer, a visitor catches “a glimpse of the three punched windows that march along the great room and that carry the memory of an old house’s thick walls,” says Decker.

Gordon Beall

Other architectural details in the addition speak the language of the Queen Anne style and recall historic homes in the area. The addition is clad in horizontal siding with a thin exposure, similar to the older portion of the house, and both old and new are topped with a Buckingham slate roof. The columns framing the new entry are slender, like those on the wraparound porch at the front of the house, but square instead of turned. “We wanted them to relate proportionally, but not mimic the old house,” Decker says.

The new stair tower is reminiscent of the front tower. “In each case, we tried to take the massing of the old house and abstract it—or differentiate it—in some way,” she says. The stone walls that form the western exterior of the foyer and the great room—a combination of horizontally laid western Maryland stone and Maryland Stoneyhurst stone—are intended to “carry the memory of an old house,” she says. They were inspired by the Art Barn, a historic carriage house in Washington, D.C., and give the appearance of weight-bearing walls from an old farmhouse.

To be sure, this house still elicits interest from passersby. But today it attracts the attention of admirers who are happy to see how a historic house has been transformed into a new old house. Thanks to a young couple and a talented architectural team—old-house lovers all—a once forlorn and forgotten piece of Maryland’s history is once again filled with life.