The handsome house was built by Victorian-era architect Daniel T. Atwood as his own residence.

Mario Turchi has always loved Gothic Revival architecture and stone houses, so when a late-1860s home came on the market near him that combined both, he deemed it “kind of like a dream come true.”

He fell in love with the house—despite the fact that it harbored wall-to-wall carpeting over the original wide-plank flooring, a clumsily applied coat of stucco over original exterior woodwork, and an inappropriate addition. “The addition wasn’t at all thoughtful; it was a remuddling for sure,” explains Maria Turchi, Mario’s wife. “It had been stuck on there to create a second-floor bathroom with a coat closet beneath, and it destroyed the roofline of the house.”

The previous owner told the Turchis that the home’s designer had also built the stunning National-Register-listed train station in Tenafly, New Jersey—information that led Mario to uncover that the architect, Daniel Topping Atwood, had authored planbooks of house designs. It turned out that the Turchis’ home was not only a textbook example of Design One, the “Picturesque Stone Cottage” in Atwood’s 1871 book Country and Suburban Houses, but it had been built as the architect’s own residence.

The discovery deepened the sense of responsibility Mario and Maria felt as stewards of the building. “From the beginning, my idea was to bring the house back to its former glory,” Mario says, and Maria was of like mind. “I come from New England, where we love preserving old houses,” she explains.

When the couple realized they needed more space for their family, finding the right person to map out the job weighed heavily on them. “It was important for us to find a really good architect,” Mario says, “one with sensitivity for the building.” The search led them to New York-based architect Donald Cantillo (who worked with New Jersey-licensed architect Kevin C. Gore, the architect of record).

Timing Is Everything

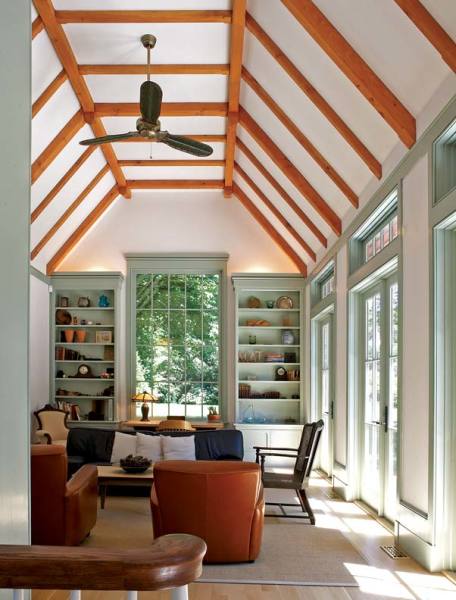

A beamed ceiling soars above the great room, which also features a wall of French doors topped by transom lights.

“I was impressed with Mario from our first telephone conversation,” Donald recalls. “He asked me for a rough estimate of the work, and when I gave it to him he said that wasn’t quite in his budget, and since he wanted to do it right, he would hold off.”

Two years later, Mario called back, and the men began plotting an extensive project that would add a great room, laundry room, garage workspace, and guest suite to the originally 2,000-square-foot house, in addition to removing the awkward second-floor bump-out, restoring the side porch, and re-creating the board siding around the oriel windows, which had been damaged beneath a layer of stucco.

In mapping out the changes, both men aimed to do justice to Atwood’s initial vision. “Mario and I both studied Atwood’s book, not so much as a guideline, but to get an idea of the spirit of the man who made the original house,” Donald says. “We wanted to add a substantial amount, but we didn’t want it to overpower the house in any way,” Mario says, perhaps channeling this quote from Atwood’s book: “Beauty of outline and proportion is as important in the design and construction of a house as the interior arrangement of the dwelling.”

To help downplay the addition’s heft, Donald stepped the garage and great room back from the original house. He created a number of sketches and massing models in order to test the best way to attach the new building to the old, finally settling upon a breezeway—an extension of the original side porch—as the connecting feature. The clever design not only sets the addition back from the street, keeping the original house as the prominent view, but it also makes a clear delineation between the original building and the new one.

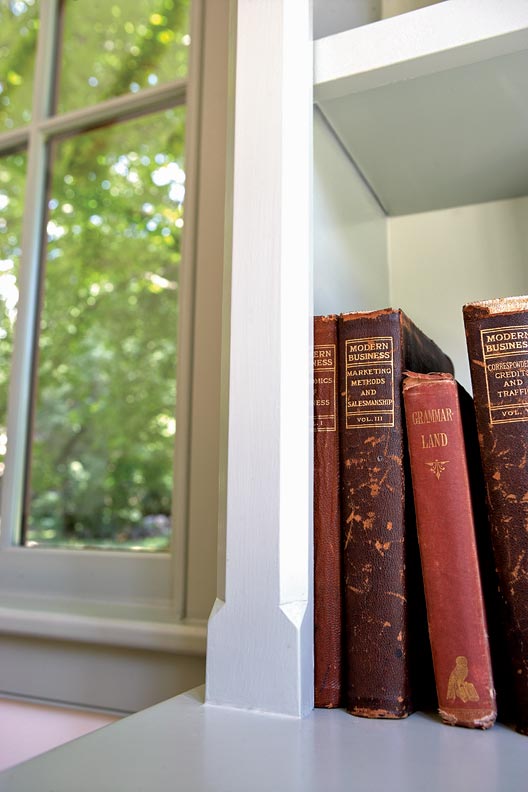

An inviting reading nook inside the new guest room.

Learning Curves

One of the trickiest aspects of the design was matching the rooflines. “The roof’s shape was extremely iconic, and we wanted to emulate the original,” Donald says. Instead of a regular gable, the ends sport a little flourish that creates a graceful curve, a design element Atwood called a “bell-cast roof,” which was popular with builders of the day. Replicating the curve proved to be a challenge, one that called Mario’s expertise (he’s an industrial designer) into play. “I laid out the bell curve on a piece of plywood and copied it to size to give the workers a template,” Mario explains.

With rooflines in perfect concert, Donald wanted a device to help show that the buildings were from different timeframes. “While we made the bargeboard the exact same shape and size, we left off the cutouts to signal that this was a secondary portion of the building,” Donald says.

The choice of building materials serves the same purpose. Creating the addition out of stone would have appeared too similar to the original house (and would have been too pricey as well). Instead, Mario and Donald opted for board siding, which matches the original detailing they unearthed around the oriel windows.

The breezeway that helps connect old to new, an extension of the home’s original side porch, boasts chamfered posts and distinctive cross-braced balusters.

Two other decisions on the roof help to meld the addition and return the home’s period authenticity. The first is the cladding—cedar shingles, as specified in Atwood’s book. It was a big financial commitment to cover both roofs in 5⁄8″ quarter-sawn cedar, but Mario never wavered: “I knew there was one chance to do it right and make it unified.”

The second is the reinstallation of three finials, which had been missing for decades, above the windows. Mario pulled the finial design directly from Atwood’s book and sent it to woodworker Steve Hanson, who precisely replicated the originals. “To me, it was a real moment of pride to see the finials back in place,” says Mario.

In the Details

Inside the house, the old and new buildings are connected via a hallway and meandering staircase.

It’s that sort of attention to detail that made the project so special. “Sometimes people—even our builder—thought we were going overboard in nailing so many of the details down. Those were the things that cost extra, but they also give the project integrity,” says Maria, whose experience as an accountant Mario credits for keeping the project’s financing on track.

The house had long been considered a neighborhood treasure owing to its provenance—it even appears on a bookmark handed out at the Tenafly library—and working on such a beloved house is often a tricky proposition. As soon as word got out that the Turchis wanted to add on, the local preservation commission vetted the plans very carefully. Mario presented the whole project, complete with drawings, to the commission at a public meeting. They were so impressed with the details that several months later, Mario was invited to serve as a member.

“I don’t know if it’s because I’m a designer, but before this project, every time I went up the driveway I felt things were missing,” says Mario. “I just wanted to see the house the way it had been.” Maria agrees that the undertaking was worth the effort. “I think it’s always worth it to work with a house and bring it back to what it wants to look like.”

The couple is thrilled with the finished project, and the neighbors seem to be as well. Passersby often ask Mario and Maria for details about the work they did, and will sometimes even venture to ask if they can come inside. “While we’re private people, we realize that it’s not just our house,” Maria says. “It belongs to the community.”