The 1725 John Chad House has traditional pent eaves between the stories.

Throughout Chester and Delaware counties, along the Brandywine River and its myriad winding tributaries, English settlers—many of them Quakers like Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn—erected ample barns of stone or brick to store their grain and shelter their farm animals. As they prospered in the fertile new land, they used the same materials to build—and then enlarge—permanent homes that were increasingly elegant.

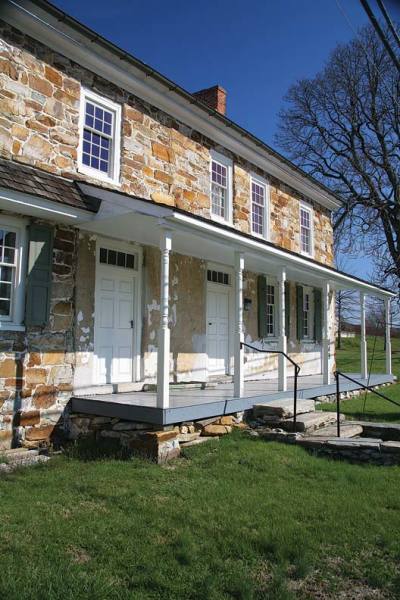

The Ashbridge House near Downingtown was built in three stages circa 1709, 1755, and 1810; the porch is a 19th-century addition.

Pennsylvania’s early Germanic settlers (the so-called “Pennsylvania Dutch”) often chose to build log houses, taking advantage of the New World’s vast supply of virgin timber. Their English compatriots also built log structures when they first arrived, but proved to have other plans for the long term. They realized that the fields, which needed clearing before crops could be planted, were an abundant source of good stone and clay. They also recognized that the skills needed to put these materials into use were close at hand, too, stored in the memories of former old-country stonemasons and brick burners.

A variety of local stone was available for building. Besides reddish-brown sandstone and blue-gray granite, the area boasts a unique, gray-green stone known as “serpentine.” In the vernacular houses of southeastern Pennsylvania, walls were made up of fairly small pieces of one or a combination of these, laid in a lively, informal rubble pattern. Brick houses also appeared very early, and brick and stone were often both used in successive additions to a single house.

The Additive House

Because they were formed in discrete sections, houses of brick and stone could be built to almost any size desired—unlike log buildings, which were limited by the length and strength of wooden beams and joists—and could be enlarged as the need arose.

Over decades, or even over centuries, wings and additions sprang up in a somewhat haphazard linear fashion, and the houses took on an informal, asymmetrical character.

One of the early revivalists of the old farmhouse tradition was R. Brognard Okie, whose 1921 Hillendale Farm near Fairview expanded the original 19th-century stuccoed house (at left) with a picturesque ramble of stepped-down early 20th-century stone additions (on the right).

Additions were usually smaller than the main block of the house and often were set slightly back from the house’s front wall. Since the additions were placed on the side of the house, rather than on the rear, the houses were generally only one room deep. These so-called “additive houses” (also known as “telescope” houses) are an enduring and distinctive feature of rural southeastern Pennsylvania.

The houses had steeply pitched roofs, with large chimneys at the pedimented gable ends. Roofs were covered in thatch, and later in wood shingles. Before the Revolutionary War, pent eaves—shallow, roof-like projections between the first and second floors—were a design feature frequently used to protect lower walls from the effects of rain.

Located in a new wing of the house, the living room at Hillendale replicates typical details used in the early 18th century, like a paneled fireplace wall and exposed ceiling beams.

A Glimpse Within

The earliest houses were compact indeed, frequently containing just a single room on each floor. Rooms on the first floor were dominated by arched, “walk-in” fireplaces on their end walls. By the 1720s, the first floor most commonly contained a two-room hall-and-parlor plan, with a steep, narrow “winder” stair in one corner by the fireplace. The stairs led to a second floor that was divided into two rooms; partitions were of plaster or vertical boards. As time passed, the more formal and symmetrical Georgian center-hall, double-pile plan, with two rooms on either side of the hall, came into fashion. Waynesborough is a large, well-developed English colonial house of this type, built as the residence of the area’s celebrated Revolutionary War general, “Mad Anthony” Wayne.

On the interior of the farmhouses, floorboards as wide as 16″ apiece attest to the generosity of the region’s 17th- and 18th-century forests. Outward-swinging, single- or double-leaf casement windows with small, diamond-shaped, leaded-glass panes were typical on very early houses, but began to disappear in the early to mid-1700s when they were replaced by double-hung, nine-over-nine or six-over-six wooden sash. Today casements are found only in restored buildings, such as the meticulously researched 1696 Thomas Massey House, a historic house museum, where long-hidden original walnut window frames pointed the way to recapturing the home’s 17th-century appearance.

The brick 1724 Abiah Taylor House, near West Chester, has an unusual second-floor balcony in the center of the pent roof, and restored casement windows. The 1995 frame wing at right was added by architect John Milner, a leader in the continuing farmhouse tradition.

The vernacular farmhouse tradition continued almost unabated well into the 19th century. Occasional examples of fine Victorian houses can be found, particularly in towns such as West Chester, but the area’s farmhouse tradition largely ignored the fancier high Victorian styles and clung to its simple, deeply satisfying stone heritage.

Though they were well-proportioned and comfortable, such farmhouses were small by later standards, prompting frequent and often extensive additions throughout the 18th, 19th, 20th, and even the 21st centuries. Fortunately, later architects were uncommonly respectful of these old dwellings. In the 1920s and ’30s, R. Brognard Okie added such architecturally sensitive enlargements to 18th-century houses that it is often hard to tell where the original building ends and the newer work begins. Okie and other architects of the between-the-wars era, such as G. Edwin Brumbaugh, also designed new houses that skillfully mimicked their 18th-century counterparts in proportion, craftsmanship, and meticulous detail. Another architect noted for his mid-20th-century restoration of traditional Pennsylvania farmhouses was John M. Dickey.

It may seem remarkable that so many stone and brick farmhouses of the 18th century have survived—and especially that so many similar ones continued to be built into the next century and beyond. But these houses were built to last—and to live with.