The view to the dining room through the galley kitchen.

William Wright

The owner admits he had no interest in Frank Lloyd Wright—nor even in historic architecture—before his house hunt a few years ago. Eliot Butler was an apartment dweller in Madison for many years. In 2008, finally looking to buy a property, Eliot read a story about a historic house for sale in the local newspaper. He contacted the owners and arranged a visit, and that was that.

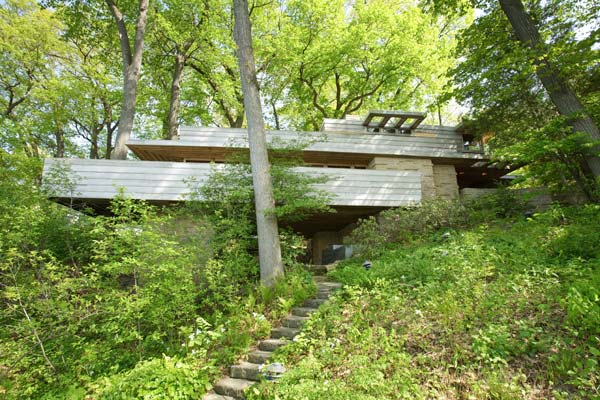

The house was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and built in 1939-40 for John C. Pew, a Madison businessman. It occupies a long, narrow lot above Lake Mendota; Wright is quoted as saying this is “probably the only house in Madison, Wisconsin, that recognizes beautiful Lake Mendota, my boyhood lake.” The famous architect had urged the Pews to purchase more land, but all they could afford was 75 feet of lakefront. Wright therefore took advantage of the narrow site, which falls steeply from the roadside down to the water’s edge, relying on a profusion of trees and bushes to make it seem private and isolated, even though neighbors were close by. Wright expertly angled the house to the lake, “on the reflex,” as he described it, making it appear to float in the forest above the deep blue water below.

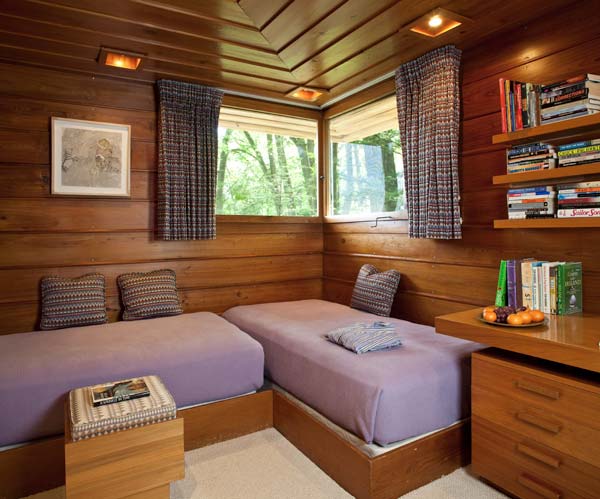

The Pews were not wealthy, and Wright was economical in his design; total cost was $8,750, the price of an average, contractor-built home of the day. Constructed both inside and out of overlapping planks of tidewater cypress screwed onto a plywood core, with accents of rough-hewn native limestone, the house is modest at 1,600 square feet. Still, rooms open easily into one another; daylight floods through a large bank of floor-to-ceiling windows on the lakefront; a wide balcony runs across the back, extending the house into the trees. The house is efficient and convenient, with cleverly constructed built-ins: banks of pull-out drawers in the bedrooms, a banquette with storage beneath in the dining room, and cabinets throughout.

Built just a few years after Wright’s famous residence for the Kaufmann family, Fallingwater, this one cantilevers over the ravine in similar fashion. Some people joked that the Pew house was the “poor man’s Fallingwater.” To which Wright is said to have retorted that, in fact, Fallingwater was “the rich man’s Pew House.”

The fireplace includes a massive boulder with stone from the reopened quarry. Note the original built-in end table; the dining area and family sitting room are in the background.

William Wright

Eliot Butler is only the house’s third owner. The second owners, the Edwards family, bought the house in 1988 directly from the Pews. During their decade of stewardship, they undertook the initial restoration. They also upgraded the kitchen, where the original plywood cabinets had split and faded, and the linoleum flooring and countertops had cracked and were stained. New kitchen cabinets faithfully reproduce the design of the originals, this time in cypress (echoing woodwork in other rooms). Durable materials now include flagstone flooring and stone countertops. The Edwardses also updated the wiring, a challenging task due to the solid walls: Cypress panels had to be removed and the new wiring snaked through channels drilled in the plywood. The family also added a dry stream bed underneath the house, in the ravine beneath the cantilever.

See also: One Wright Pilgrimage

Plenty of work remained for Eliot. He laid a new rubber roof, reproducing the original, and installed a new boiler. But he was careful not to tamper with Wright’s original “gravity heating” system, in which heat from hot water pipes in the floors rises through quarter-inch gaps in the narrow cypress floorboards to provide diffuse radiant heat. Windows and doors once again open and shut properly. Over time, the eaves over some of the windows had been lowered to allow air to circulate, but this had prevented the windows from opening properly, so Eliot restored the original design. Decayed cypress planks on the exterior were replaced, and marine paint was stripped off upper and lower terraces. The cypress woodwork inside, aged to a mellow golden brown, required little more than light cleaning. A few areas with white streaks were corrected by rubbing with a mixture of Vaseline and ash.

The Edwardses left Eliot with three original 36′-square cypress tables Wright had made for the house, along with four contemporary cushioned wood chairs compatible with their design. Kevin Earley, a talented local cabinetmaker, had made two glass tables and several cabinets for the Edwardses; these also came with the house. Eliot bought a 1949 Taliesin ‘Origami’ chair and paired it with a contemporary but complementary ‘Alphabet’ modular sofa from Italian designer Piero Lissoni.

Eliot Butler now says that he never realized he could be so passionate about a house. He has felt, as he sits on one of the terraces, that Wright could have built the house with him in mind. His preservation efforts haven’t gone unnoticed: He received the Historic Preservation Award from the Madison Trust for Historic Preservation in 2010. The house is now on the State Register of Historic Places.

Frank Lloyd Wright Reading Recommendations

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE ROOMS Interiors and Decorative Arts by Margo Stipe (Rizzoli 2014) Intimate immersion inside the Prairie houses, Fallingwater, Hollyhock House & more.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PRAIRIE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2006) Interiors and details of over 70 extant buildings of the Prairie School years. How Wright broke from Beaux Arts symmetry to create “a tartan plaid of main spaces and secondary spaces, of public rooms and circulation spaces”—with brilliant results.

THE PRAIRIE SCHOOL: Frank Lloyd Wright and his Midwest Contemporaries by H. Allen Brooks (Norton 2006) From its beginning to its end, Prairie School beyond Wright. Discusses the architects’ various contributions.

HOMETOWN ARCHITECT: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois by Patrick F. Cannon (Pomegranate 2006) Houses 1887–1913; this book is the pilgrimage documenting 27 Wright houses in Oak Park and River Forest. Photos include interiors.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2005) From the 1908 Prairie School Robie house in Chicago through his textile-block houses in Los Angeles, and on to Fallingwater and Taliesin West, here are FLW’s residential commissions all in one huge volume.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S INTERIORS by Thomas A. Heinz (Gramercy Books 2002) Shown are 1,000 interiors, including houses and public and corporate buildings, from throughout Wright’s career. Horizontal lines, natural elements, concrete, and brilliant use of three dimensions.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S GLASS DESIGNS by Carla Lind (Pomegranate 1995) Innovative design for windows, skylights, and decoration.