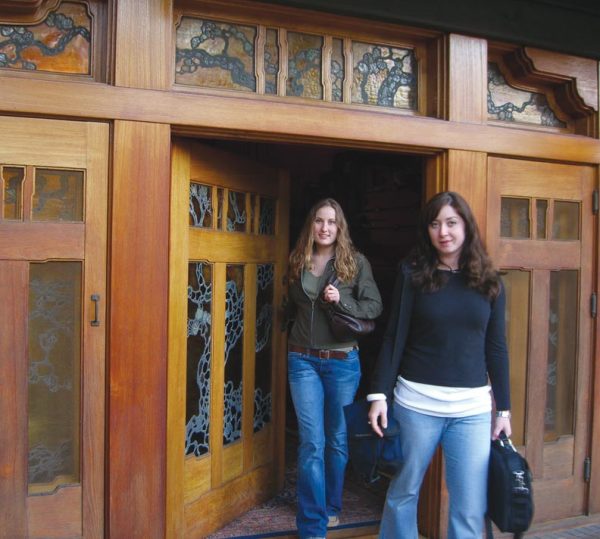

Friends before they were housemates, Jana Cooper (left) and Ewa Ziabek (right) faced stiff competition for the privilege of living at the house. The distinctive wide and low from door has an art glass window depicting the tree of life. (Photo: Courtesy of Jana Cooper and Ewa Ziabek)

One day last year, Ewa Ziabek toured an extraordinary house that 30,000 people visit annually, but unlike her fellow tourists, Ziabek wasn’t there simply to marvel at exquisite art glass windows or the artfully exposed structure of a teak and mahogany staircase, its smooth wooden pieces fitted neatly together like those of a jigsaw puzzle. She was sizing up her new home.

Since 1967, a remarkable changing of the guard occurs every summer at the Gamble House in Pasadena: Two students about to enter their final year at the University of Southern California’s School of Architecture relieve two recent graduates of their responsibilities as the home’s only live-in house sitters. The Scholars in Residence program, as it is known, may be this country’s most unique architectural fellowship, not only for its coveted prize, that of living rent and utility free for a year in a house that many regard as the most spectacular Arts & Crafts home ever built, but also for the program’s unusual approach to historic preservation: using student residents instead of cameras, security guards, and fences to protect and watch over the house.

Besides keeping an eye out for intruders, leaks, and burned out light bulbs, the students experience the USC-owned Gamble House the way it was originally intended—as a home—and to a lesser degree, enable visitors to experience it that way, too. Nonetheless, after nearly a year living there, says Ziabek, “I’m still amazed that I have a key to the front door.”

House Rules

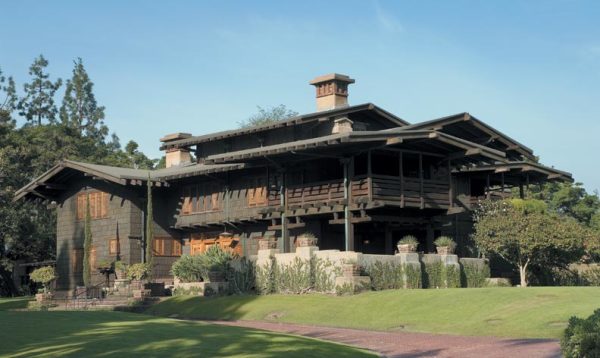

With its priceless original 1908 fixtures and furnishings and 8,000 square feet of space, the Gamble House is not your average home. Renowned architects Charles and Henry Greene designed the house for the Gamble family right down to the carpets and furniture. USC inherited the property from the Gambles in 1966 and has overseen it ever since.

With eaves two to three times deeper than houses of the period, the 1908 Gamble House was unusual even in its day.

Ziabek, who grew up in Poland, and her fellow scholar in residence, Jana Cooper, had to compete with about 15 to 20 other students for the privilege of living at the house, writing three-page essays about why they should be selected and then making the first cut by USC faculty before going on to final interviews with some of the docents. The winning candidates not only must act as responsible stewards of the house but also the willing housemates of visiting tourists and the 150 volunteers and staff who work there at daytime. Although the students don’t give tours, they do earn their keep by setting up tables and chairs for the many outdoor functions held on the premises.

Then there are the eight pages of rules and regulations that the docents go over with the students when they first arrive. Friends are allowed to visit but not in the main rooms, and the house cannot be left unattended overnight. While Cooper and Ziabek each have their own bedroom and share a bath on the second floor where the servants’ quarters used to be—an area not on the tour—much of the house remains off limits even to them.

Both women have come to appreciate the house’s architectural details, including its exotic wood, such as teak, and the rounded edges of these protruding beams in the entry hall.

They can’t, for instance, curl up with a book on the cozy inglenooks that flank the living room fireplace or cook spaghetti in the original kitchen the way earlier generations of live-in students once did. Those privileges were dropped because “it was just too hard on the house,” says Gamble House spokesperson Bobbi Mapstone. Instead, Cooper and Ziabek cook their meals in a modern, fully equipped kitchen in the basement and mostly glimpse the main rooms as they walk by during the day or make their rounds at night to check that doors are locked and the lights turned off.

Daily Life in a Landmark

Still, the parts of the house the students do enjoy fully are not to be sneezed at. In addition to their rooms, each a modest L-shaped space with Gustav Stickley furniture and south-facing windows, there are three second-story sleeping porches, a servant’s dining room, basement studio, and spacious finished attic that they can use. Once a year, usually at graduation, they are allowed to have dinner with family and friends in the formal dining room. Cooper is particularly fond of the sleeping porches. Like so many live-in students before her, she occasionally drags an air mattress onto a porch and sleeps outside, her alarm clock the bright California sunshine that awakens her around 7 a.m.

The third-story finished attic made from gleaming Oregon pine beckons Ziabek with a birds-eye, 360-degree view of the grounds. Narrow windows extend all the way around and up to the rafters, giving the room the feel of a luxurious tree house. The attic has a television set to which Cooper and Ziabek once connected their DVD player in order to watch movies there.

A common feature for houses back then, sleeping porches are “like camping in a really nice tent,” says Jana Cooper.

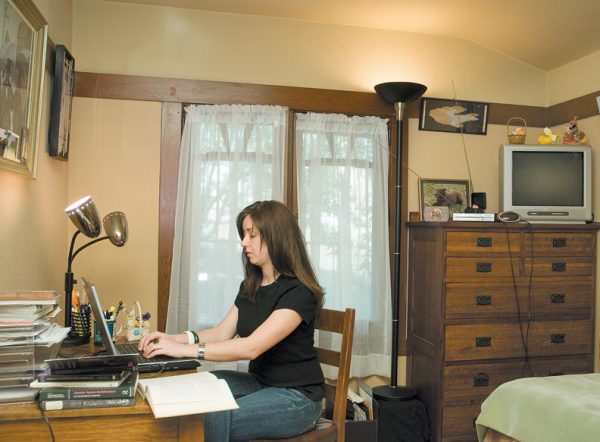

While the house was built with electricity, it retains the dim light fixtures from a century ago; only the student’s rooms have strong enough light to read by at night. In a further concession to modern conveniences, their rooms are also equipped with enough sockets to accommodate the small truckload of electronics—computer, scanner, printer, stereo, television, and DVD player—that accompany students to college these days. “It sounds crazy, but our rooms even have wireless Internet,” says Ziabek.

Outside, there are no restrictions to where they can go. On pleasant mornings, Ziabek takes her cereal and eats it perched on a low stone wall surrounding the brick terrace. She and Cooper have set up a table outdoors and invited over all their friends to a home-cooked Chinese dinner on warm evenings.

The art glass window in the dining room, like the one in the front door, looks completely different during the day, when it’s lit from the sun outside, than at night when it glows by reflecting the light from indoors.

If the days are filled with the steady hum of strangers’ voices and the playful shrieks from the kindergarten next door, dusk is what Cooper calls decompression time because everybody is gone. “You feel like the house is resting after a long day, the same as you.” It’s also when both women say the house feels like theirs. Cooper walks around in her pajamas, and with no tour groups to squeeze past, Ziabek uses the main staircase instead of the servants’ stairway off the kitchen.

Peaceful, however, isn’t the same thing as silent. “All that wood is expanding and contracting so that you’ll hear things creak,” says Cooper, who was spooked by the sounds the first night she was there. For Ziabek, it’s the darkness that’s unnerving. “The house feels completely different at night than during the day, when it’s light and airy,” she says. At night, the dark wood paneling and crossbeams create a more somber mood. Legend has it that Aunt Julia, the Gamble family member to live in the house the longest, haunts the place. Ziabek doesn’t believe in ghosts and certainly hasn’t seen evidence of one, but nevertheless, she says, “If I’m home by myself late at night and I want to go down to the kitchen for a snack, I’m too scared to go.”

Impressions to Last a Lifetime

Wireless Internet access and bright lighting are 21st-century necessities found only in the students’ bedrooms.

No matter how much the Gamble House might feel like home, Ziabek and Cooper never quite forget that they’re living in a museum. Whenever Cooper enters one of the main rooms to turn off a light, she deliberately steps into the middle of the rug to avoid treading on the more walked-on edges, as a docent once instructed her to do. “You think twice before you kick off your shoes or lean on a chair,” says Bob Godowski, a former student resident who lived in the house in the late 1990s.

Then, there are the occasions when the house, like so many old houses, decides to spring a leak. Godowski recalls one torrentially rainy day, not long after he moved in, when he heard the sound of gushing water while he was working in the basement studio. Alone in the house, he got up to investigate and discovered rainwater streaming into the basement. Outside, he found the source of the problem: a large hole in the gutter from which water was seeping in through the ground at the side of the house instead of being directed away from it. “Of course I panicked,” says Godowski. All he could think about was how this monument of a house, significant to a sizable number of people, was about to be flooded on his watch.

Because of his hasty exit to trace the source of the leak, Godowski had run outside in a T-shirt, boxers, and bare feet and had little on hand to fix the leak. So, he gamely stripped off his T-shirt and used it as a plug. As he was standing there, half naked and soaking wet, in the midst of studying his handiwork, the sprinkler system came on and drenched him further. “I’m sure the neighbors were looking out their windows and thinking, ‘There goes the neighborhood,'” says Godowski.

Made from arroyo stones and clinker bricks, the terrace is an ideal spot to savor the peace and quiet during the early morning hours or at dusk, when both tourists and docents have gone.

Of course, students being students, not all goings-on at the house would meet with docent approval. At occasional functions held to unite all of the previous student residents, “it doesn’t take long before the room is buzzing about who threw which clandestine party when,” says Gamble House director Edward Bosley.

In the fellowship’s nearly 40 years of existence, no student has ever broken or damaged anything in the house, something that Bosley attributes to “architecture’s civilizing effect on students,” and he would know. When Bosley was a student at the University of California at Berkeley in the early 1970s, he and his fraternity, Sigma Phi, lived in and lovingly maintained the Thorsen House, which the Greene brothers also designed. (Sigma Phi still maintains the house today.)

The original kitchen on the ground floor is strictly for show, so the students cook their meals in this fully equipped modern kitchen in the basement, the same one caterers use for the many functions held on the premises.

Just as living in that house influenced Bosley’s career (he has also written books about Arts & Crafts architecture), a few of the previous Gamble House residents have gone on to become restoration architects, and one of them even served as the project architect on the house’s recent exterior restoration.

Neither Ziabek nor Cooper plans to become a preservation or restoration architect, but both acknowledge that the house has influenced their designs. “The house is about details,” says Ziabek. “Wherever you turn, inside or outside, there’s always something happening with the walls—things sticking out or different wood, angles, colors, and textures.” So now, when Ziabek designs buildings, she pays attention to details and designs all the way around the structure, not just the part facing the street.

For Cooper, the house has taught her to consider how the same architectural feature appears in a different light. The front door, for instance, has glass panels depicting the tree of life with its branches spread out across the wide double doors. In the evening, when the doors are backlit by an outside porch light, they seem to glow in the darkness of the dimly lit foyer, while in the mornings the sun shines through the glass, bathing the front hall in bright amber light. “The Gamble House is constantly reminding me of what great architecture should be,” says Cooper. And therein lies its downside, because she adds, “this will probably be the nicest place that I will ever live. My next apartment is really going to depress me.”