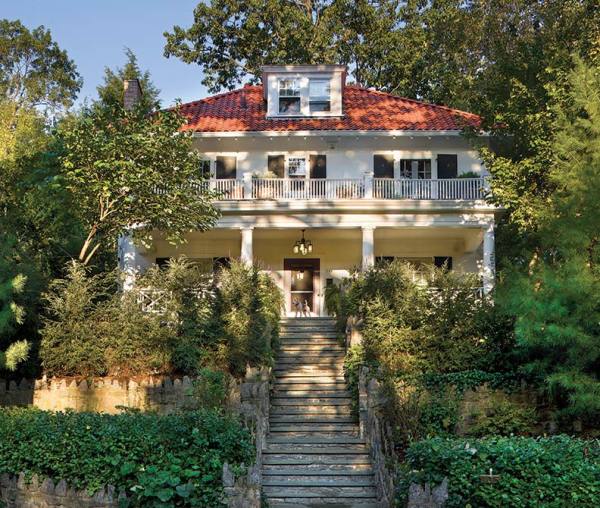

Architect Gary Brewer breathed new life into this Yonkers Foursquare, which he calls home.

Francis Dzikowsk

For many old-house observers, Arts & Crafts may be one of the most confusing architectural styles. The name sounds improbable—more like a Girl Scout merit badge than a house style. And what does an Arts & Crafts-style house look like anyway? Is it a Craftsman bungalow, a Foursquare with bracketed eaves, a quaint cottage, or perhaps an architect-designed Prairie house?

The answer: Yes.

Practically the only common factors to be found in all Arts & Crafts houses are those that encourage an informal but cultured lifestyle:

- an open floor plan

- natural materials such as stone, brick, and wood

- airy, light-filled rooms that encourage interaction with the outdoors

- the tasteful arrangement of a few well-designed, decorative, and useful objects

Arts & Crafts stained-glass window.

Eric Roth

The term Arts & Crafts refers to a broad social and artistic movement that took shape in Great Britain and Europe in the middle of the 19th century and then leapt the Atlantic to garner wild acclaim in the United States at the turn of the 20th century. It encompasses interior design, fine and decorative arts, printing and publishing (book design, illustrations, posters, and advertisements), jewelry and tableware, textiles and wallpaper, furniture and ceramics—and, oh yes, houses.

A Tasteful Standard

The 1901 Davenport House in River Forest, Illinois, was designed during Frank Lloyd Wright’s brief, little-known partnership with Webster Tomlinson, and resembles several other early Wright houses.

The Arts & Crafts movement began as a revolt against bad taste. And bad taste, Arts & Crafts devotees believed, was embodied in the flood of poorly designed, carelessly made, overly decorated, useless household goods that resulted from the Industrial Revolution. So much stuff, so little beauty and utility.

Tastemakers and social critics like England’s William Morris shuddered at the sight of it. “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” Morris urged his readers. Well-designed, handcrafted objects were admirable; factory goods were an abomination.

In architecture, Morris and his followers advocated the examples of Gothic church architecture and English vernacular house styles. Europeans, too, looked to their own regional building styles. This preference for homegrown architecture partly explains why the Arts & Crafts style is so varied.

In Europe, the Arts & Crafts movement flourished in several distinctively regional subsets, particularly Austria’s Secession Movement, Germany’s Jugendstil, and France’s Art Nouveau. All turned away from mass production and toward hand craftsmanship for both buildings and objects.

Sidelights flanking the front door were restored to their original configuration. The replacement door is by cabinetmaker Charles Saenger.

William Wright

Americans also sought a simpler but aesthetically richer life, and they were enthusiastic about their own diverse architectural heritage. But Americans were not about to give up mass production. On the contrary, they believed factories were as capable as individual craftsmen of producing quality design—and at a much lower cost, making it available to more people.

Among the first to trumpet the value of factory-made objects for American homes was Frank Lloyd Wright, who addressed the topic in 1901 in his famous Chicago lecture, “The Art and Craft of the Machine.” (Wright, it must be said, did not espouse mass-produced objects in houses he himself designed.)

Edward Bok, editor of The Ladies’ Home Journal, the era’s largest and most influential women’s magazine, quickly picked up the Arts & Crafts banner. In 1895, the Journal initiated a long-running series of Arts & Crafts-influenced house designs by noted architects, including William L. Price, E. G. W. Dietrich, and Frank Lloyd Wright. Charmingly restrained room layouts by luminaries such as Will Bradley conveyed Arts & Crafts values to millions of readers.

Better lines, better proportions, better trim—and an Arts & Crafts house rises in the neighborhood.

Gridley + Graves

The biggest promoter of the American Arts & Crafts movement, however, was an erstwhile furniture-maker named Gustav Stickley. From 1900 until 1916, Stickley’s hugely popular magazine, The Craftsman, encouraged readers to build, furnish, and decorate their own homes using Arts & Crafts principles. Simple furnishings from the Stickley factories were featured in the magazine’s pages, which also provided free designs for Craftsman houses. This, of course, inspired countless bungalows and Foursquares that still dot the streets of suburbs around the country.

Stickley’s enthusiasm for the bungalow helped the style spread rapidly during the first quarter of the century—so much so that the words “Craftsman” and “bungalow” are now inextricably linked in the old-house lexicon. Stickley was no purist, but he urged the use of handmade decorations, from pottery to silver to textiles—even made by the homeowners themselves.

Handmade Virtues

In Kansas City, Missouri, Mineral Hall (built in 1913 by Louis Curtiss), with its ornamented, arched entrance, is probably the best American example of Art Nouveau architectural features, rarely seen in this country.

Arts & Crafts architecture was so closely tied to interior design that the furniture and fittings of a house, even more than its external appearance, determine its place in the Arts & Crafts camp. Simple but sophisticated design and exquisite craftsmanship were hallmarks of the movement.

Handmade ceramics—including tiles for both indoor and outdoor use—became a thriving Arts & Crafts industry throughout the country. Rookwood, Pewabic, Batchelder, Van Briggle, and a host of other potteries flourished. Potteries and other Arts & Crafts industries, in fact, provided the first entry for large numbers of women into the world of design.

As in England and Europe, natural building materials such as fine woods, stone, and brick were favored. Americans, however, readily took to newly improved, fireproof concrete building products. Henry Chapman Mercer’s famous Moravian Pottery and Tile Works factory in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, which specialized in glazed tiles in medieval patterns, was constructed entirely of concrete, as was Fonthill, Mercer’s castle-like home nearby.

Architectural Legacy

Dozens of architects throughout the United States designed Arts & Crafts houses, drawing on architectural styles traditionally found in the region. In the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic, English styles were generally emphasized for country homes and town houses. Prominent eastern architects included William L. Price, Aymar Embury, Wilson Eyre, and Joy Wheeler Dow.

With a broad terrace on the first floor and a covered porch on the second level, the back of the house is oriented towards the distant ocean view.

Brian Vanden Brink

California was an early hotbed of Arts & Crafts design, led by Pasadena’s Charles and Henry Greene. The Greene’s Gamble House, often called the “ultimate bungalow,” was an Arts & Crafts showplace. It was one of many houses that illustrated the influence of Japanese design on their work, especially the use of wooden construction. A bevy of Bay Area designers put their own twist on shingled wood construction, especially in San Francisco, Oakland, and Berkeley. Among them was Bernard Maybeck, whose shingled houses often showed Gothic references. Julia Morgan, famous as the designer of William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon, carried out many other Arts & Crafts commissions in California.

As is typical of Wright’s Prairie School homes, the front entrance here is concealed from the street. Instead, it is the front porch, protected by an expansive, cantilevered roof, which is the highlight of the façade.

Andy Olenick

The Prairie School architects of Chicago—including Purcell and Elmslie, George Maher, Walter Burley Griffin, and Marion Mahoney (only lately given her due as a designer)—developed and spread Frank Lloyd Wright’s message. Henry Trost’s work in El Paso and elsewhere reflected his training as a Prairie School architect, while in Kansas City, Louis Curtiss took a very different approach; his Mineral Hall may be America’s only true Art Nouveau house.

In the Southwest, Mary Jane Colter was among a number of women architects contributing to the movement with her distinctive Southwestern-influenced hotels and restaurants along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad. Even the South had its Arts & Crafts architects, among them Henry J. Klutho of Jacksonville, Florida.

As a movement, Arts & Crafts didn’t survive World War I. Postwar houses most often wore eclectic European revival styles—from Tudor to Spanish to Mediterranean. Nonetheless, by banishing Victorian decorative excess, the Arts & Crafts pushed American architecture decisively toward Modernism and left a rich legacy shared by thousands of old-house owners today.