This story was originally published in Traditional Building magazine.

Paul Edmondson

National Trust for Historic Preservation

1 How did your professional career begin? How have your roles shaped your perspective? After graduating college, I worked for several years in Upstate New York as an archaeologist. Most of that work was to fulfill the requirements of federal and state environmental and preservation laws—laws that were intended to ensure that projects supported with federal or state funding did not damage historic or archaeological resources. That intersection of law and history fascinated me, and after a while I decided to pursue the legal side. My goal was somehow to combine my interest in preservation with my interest in law, but it was totally a long shot—I didn’t know any preservation lawyers, and the field of preservation law was really in its infancy. Thirty-plus years later, I consider myself very lucky to have spent most of my professional career as an advocate for historic preservation.

2 What brought about a passion for preservation? Why do you believe it’s important? My passion for preservation really began as a passion for history. I’m one of those people who firmly believes that we can’t tell where we are going without understanding the path that others have taken before us. And nothing makes history more real than standing in the place where history happened, whether it’s a Civil War battlefield or the corner of Haight and Ashbury. Preserving historic places helps us to define our identity, at the personal level, at the community level, and at the national level. These places resonate with the past, good and bad, and can inform and inspire the future. They can help us celebrate our successes, and also illuminate our mistakes. But the more I learned about the preservation movement, the more I understood that preservation has many other benefits at the community level. These include environmental sustainability, economic vitality, and simply the benefit of defining community character in a society that finds it easy to fall into a pattern of favoring the new and nondescript.

3 Are there certain types of places you feel are more worthy of preservation than others? Say homes vs. public buildings or vice-versa? Each has its place. Iconic landmarks serve as statements that speak to the higher aspirations of our society, or define major events or movements in history, or that represent important architectural achievements. But the places we live, work, learn, play, and pray—the more ordinary places—are important too, because they represent what we value in our daily lives, or tell individual stories that reflect our history as a society. There are challenges in preserving each type of resource. Many iconic landmarks are threatened because of disinvestment, or changing societal norms, or because their original uses are no longer viable; preserving them as monuments or museums is rarely the answer, and so the challenge is to find opportunities to repurpose and reuse those places in a way that respects their history but gives them economic viability. And historic neighborhoods are living, breathing places. The goal of preservation isn’t to stop change, but to manage change in a way that respects and celebrates the historic character and distinctiveness of our communities.

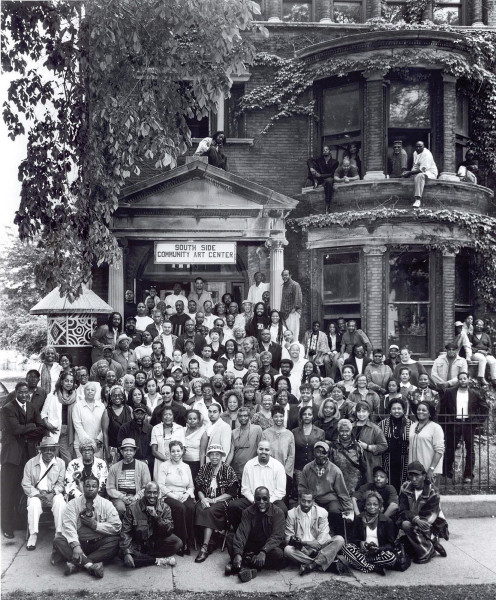

South Side Community Art Center

South Side Community Art CenterSouth Side Community Art Center Chicago, ILDesignated a National Treasure by the National Trust and recipient of grant funding from the AACHAF.

National Trust for Historic Preservation

4 Can you tell us what plans are on the horizon for the National Trust for Historic Preservation? The National Trust is currently pursuing four major strategic priorities.

The first of these priorities may seem obvious, since it is the core of our mission: to save historic sites. We are doing that in two interrelated areas of work that reflect the mission of the organization across its 70 years of existence—stewardship and advocacy.

Our stewardship is grounded in our 28 National Trust Historic Sites, which we began acquiring in 1952, and where we care for complex cultural resources—historic buildings, landscapes, and collections—while also developing relevant and inclusive uses and programs for them. We do this work with a host of remarkable partners and we do it with the shared goal of ensuring that these remarkable places are vital community assets for the long term. We also support saving historic sites through our grant programs and technical assistance provided by our field offices, as well as initiatives that highlight and support these special places, such as our Historic Artists Homes and Studios network or our Distinctive Destinations program.

The other way in which we save historic sites is by taking direct action through our advocacy campaigns, such as our National Treasures program, that bring to bear the full range of our expertise in legal, policy, media, and other forms of public engagement. These campaigns take many forms but they are always opportunities to model solution-oriented preservation. We also take direct action to save historic sites through our easement program that protects commercial and residential properties while allowing them to continue to evolve and remain in active use.

This combination of stewardship and advocacy is a powerful one, and we intend not only to continue this work, but also to increase its impact across all the incredible historic places where we are involved.

Little Havana

Little HavanaLittle Havana Miami, FLNamed to the list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places and also later designated a National Treasure.

Steven Brooke Studios

Our second strategic priority is telling the full American story. What we choose to preserve reflects our current values, and for too long the places that represent the history of minorities and women in this country have not been well-recognized, and their stories have not been properly told and celebrated. We are working to change that, and will continue to invest in programs like our African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, as well as our newest initiative, a Campaign for Where Women Made History. Both of these programs are bringing important new investments in areas that have been underrepresented in the way that we tell the history of this country. We are also focused on telling the full American story at our own National Trust Historic Sites, working to address their complex histories and sharing that process with the public and our colleagues along the way. Through programs like our National Treasures and 11 Most Endangered Historic Places campaigns, we also are telling and celebrating the stories of Latino communities, Asian American communities, as well as the struggle to establish LGBTQ rights.

Our third strategic priority is to build stronger communities. Main Street America, for example, a program created by the National Trust in 1984, is thriving today by helping communities recognize and celebrate the cultural and economic value of historic downtowns. On the policy side, we have worked closely with local partners to improve preservation planning in communities as different as Philadelphia and Miami’s Little Havana. We are also working hard to improve access to incentives like tax credits for preservation at both the federal and state levels, since investments in anchor preservation projects can spark transformational revitalization across communities. We don’t just talk about this work; each year we invest millions of dollars in grant support for preservation projects, and we connect investors with developers to support the use of rehabilitation tax credits to help underwrite preservation projects through our National Trust Community Investment Corporation.

The fourth strategic priority is investing in historic preservation’s future as a field, and we are doing that by building stronger connections with our preservation partners across the country, and improving our training, convenings, and educational programs for practitioners. Our annual PastForward conference draws people from around the country who are passionate about preservation and connects them to each other and to the broader movement. Right now, we are taking a fresh look at our approach to all our trainings and content—and how they can best serve the entire field—and I’m excited to see where that leads us. Ultimately, preservation is best done in partnership with local advocates, community leaders, and ordinary citizens, and we intend to strengthen those partnerships going forward.

Nina Simone’s Childhood Home

Nina Simone’s Childhood HomeNina Simone’s Childhood Home Tryon, NCDesignated a National Treasure and also AACHAF grant recipient.

Nancy Pierce

5 What are your biggest challenges? Perhaps the biggest challenge is to address the broad misconceptions about our work, and particularly the idea that preservation means freezing historic places, as if we could suspend them in amber. If historic places are not considered to be living assets in the communities in which they are located, they will be at risk—and to be assets they must be economically viable. Often people don’t realize how much these places are part of their communities until they are threatened or even lost. Part of our work is to help people see and appreciate the distinctive old places all around them, and then to find ways to keep them as useful parts of community life. Sometimes that means maintaining historic uses, but often that means adaptive reuse. Both require creativity, flexibility and adaptability to realize the full potential of these important places for people today.

6 What is inspiring you right now? Probably the most inspiring work that we are doing today is our effort to recognize and support historic places associated with African American history. There are a tremendous number of historic sites associated with African American history, but many of these places have been ignored, and in many cases neglected. Their stories deserve to be told. With support from a number of major foundations we are well on our way to our $25 million fundraising goal for this initiative, through which we are providing grants, technical assistance, and direct support. The need is great. For example, we just closed applications for our latest round of about $1.6 million in grants, and we received 540 applications for projects representing almost $58 million in funding needs. We can only serve a small fraction of this need.

Shockoe Bottom

Shockoe BottomShockoe Bottom Richmond, VANamed to 11 Most Endangered List, named a National Treasure, and AACHAF site.

National Trust for Historic Preservation

7 How do we keep preservation relevant in today’s world? It is not so much a matter of keeping preservation relevant, but articulating how it is relevant in today’s world. In fact, preservation often has an essential role to play in the hottest topics in American society. What could be more relevant than our work through the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund to tell the full story of America?

And we shouldn’t be defensive about wanting to preserve our history and the character of our communities: we have seen first-hand how preservation provides a host of benefits, among other things serving as a catalyst for revitalization, economic development, tourism, and sustainability. The National Trust’s role—as both a stewardship organization and an advocacy organization—is to help define and demonstrate those benefits, and in the months to come we will be very focused on doing so.

8 How will your expertise as a lawyer with a depth of experience in historic preservation shape your leadership at the Trust? As a lawyer, I believe in the power of advocacy—of standing up and shouting “no!” when the bulldozers are on the threshold. But through my experience as the National Trust’s general counsel, I have always worked to find common ground. Litigation, for example, is an important tool, but it should always be a last resort. Coming up with the creative compromise has been an essential part of the success that we have had. In many cases the forces that threaten historic places can be redirected to less sensitive locations, or demolition can be avoided by identifying incentives for preservation. But often alternatives won’t be given a chance without the tool of strong public advocacy.

9 Do you see a backlash against preservation in the current political environment—roll backs on local preservation commissions for example? How will you address such challenges? Overall, historic preservation has strong support across the political spectrum; we like to think of our movement as “purple,” not red or blue. At the same time, of course, opposition does exist—particularly around the issue of local preservation controls, even though local historic districts represent only a small portion of the overall building stock in most communities. Arguments made in opposition to local preservation laws are often based on isolated anecdotes and generally ignore the broader benefits that such laws provide, including stabilized property values, walkability, diversity of business uses, community cohesiveness, and environmental sustainability, among others. Again, it is important that we articulate those benefits.

Pope-Leighey House

Pope-Leighey HousePope-Leighey House Alexandria, VAA National Trust Historic Site, this Usonian house was developed by Frank Lloyd Wright as a means of providing affordable housing for people of moderate means.

National Trust for Historic Preservation

10 How is the drive for net zero and other energy conservation matters shaping the role of historic preservation today? As far as energy conservation goes, historic preservation is one of the most sustainable practices possible: the high carbon footprint of new construction, even of the most energy-efficient buildings, far exceeds the sustainable practice of preserving and adaptively using buildings that were constructed years ago. And that doesn’t even count the enormous amounts of waste materials that go into landfills when older buildings are demolished and replaced with new buildings. The saying that “the greenest building is the one already built” is absolutely true. In addition, many historic buildings already come with sustainable building features designed to keep their original occupants cool in hot summers and warm in cold winters.

At the same time, preservationists are as sensitive to the climate crisis as anyone else, and we are working to incorporate green practices in the management of historic sites. Building rehab projects often include such features as solar panels, green roofs, and sustainable landscape features that lessen water use or minimize runoff. At the National Trust, we have initiated a project we are calling “Sustainable Stewardship,” through which we will identify and implement sustainable practices within our portfolio of 28 National Trust Historic Sites, as models for other historic sites across the country.

11 Where do cultural diversity and historic preservation intersect? Cultural diversity and preservation intersect at all levels. Part of our responsibility as a national organization is to ensure that the work we are engaged in as preservationists reflects the diversity of America, which is why one of the National Trust’s priorities is to tell the full American story. We also have a responsibility to ensure that the field itself reflects the diversity of America, which is why the National Trust has a number of paid internship programs and scholarship funds which are helping to make the broad field of preservation more inclusive of people with a variety of different backgrounds. Programs such as our HOPE Crew are engaging young people, including participants from Job Corps training programs and architecture students at Historically Black Colleges and Universities, with Hands-On-Preservation-Experiences, while our Mildred Colodny Scholarship program helps to make graduate studies in a preservation-related area of study more affordable.

Acoma Sky City

Acoma Sky CityAcoma Sky City New MexicoA National Trust Historic Site that is owned and operated by the Pueblo of Acoma, the adobe houses, plazas, and walkways on the 367-foot tall mesa have been used for nearly one thousand years, making Acoma Sky City the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States.

Douglas Merriam

12 Are there specific strategies the Trust is undertaking to attract corporate or foundation support for its work. The most effective strategy to attract corporate and foundation support—which is critical to our work—is to combine impactful, ambitious work with true partnerships around issues and values that we hold in common. Our longstanding partnership with the American Express Foundation, for example, reflects our common appreciation of cultural heritage as a valuable resource that benefits all Americans and together we’ve given away millions of dollars in funds to great preservation projects in communities all around the country and demonstrated the power of social media engagement with preservation. Our African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund is the largest fundraising campaign every undertaken on behalf of these resources and it has attracted strong support from foundations that recognize and celebrate diversity as a fundamental value in our society, including the Ford Foundation, the Andrew Mellon Foundation, the JPB Foundation, and other major funders. Our National Fund for Sacred Places just received its second $10 million grant from the Lilly Endowment so we can continue to provide critical support for historic religious properties across the country through capital grants and technical assistance that are combined with capacity-building and development training from our long-time allies at Partners for Sacred Places.

Our relationships with these and other funders and partners reflect an alignment of our interests, with the public as the real beneficiary.