Responding to historical precedents, architect Peter Zimmerman created a series of additions that blend with the original eighteenth-century stone structure.

Old houses tell stories. We discover their origins in stone foundations and door hardware, gather hints of hardships from the scars they proudly bear. We piece together chronologies from major alterations—a new entry added to reflect changing fashions, a wing attached to accommodate the next generation of children. New houses, on the other hand, can be as mute as sleeping babes.

Not so with a new addition designed by the Pennsylvania-based firm of Peter Zimmerman Architects. The addition—a whole new house, really—envelopes the earliest section of an eighteenth-century Pennsylvania farmhouse, creating an entirely new facade and rear wing. To fulfill the homeowners’ desire to live in a faithful “interpretation of a historical house,” says Zimmerman, he took great pains to invent a history for the new home while also making the new construction compatible with its centuries-old counterpart.

“These Pennsylvania farmhouses grew over time,” says Zimmerman, who works on projects up and down the East Coast but most often here in the sylvan countryside near Philadelphia. “They tell a clear story about how the volumes went together and were added on to at different periods.” So for this new house, he and his team of architects followed a similar story line, only they drew from fiction rather than fact. The result? A new house with the whimsy and charm of a home that grew organically over many generations.

Like all good design, this project relies on proper proportions. Before he delved into the details that make this a winning new old house, Zimmerman considered the home’s relationship to its surroundings, including a mill pond and mill ruins, pristine woods and pastureland, and other early American farms. Even though the original farmhouse had colonial origins, a towering Georgian mansion would have seemed out of place. “To create a house of this size without overpowering the site, you need to break the mass down into multiple volumes,” Zimmerman says. His farmhouse-scaled two-story home stretches out in the shape of a T, with the entry wing and kitchen forming the stubby leg and the rest of the home forming the T’s long cap.

This hallway just off the front entrance hall in the new addition is flanked by a row of windows looking into the kitchen. The three-piece beaded door casing with backband is historically appropriate, as are the window casings.

Sticking to the time period of the original farmhouse, the architects designed an asymmetrical Georgian-derived fieldstone house with very little ornamentation. The main three-bay mass, the most formal part of the entire house, features a noble entry—the crisp white paint in striking contrast to the gray and tan stone—boasting a traditional Georgian entrance with fanlight. Like the rest of the home, the entry carries a story line: “As the English and Welsh settled this area, they built simple homes to shelter themselves,” Zimmerman explains. “A farmer might have traveled to Philadelphia, seen a more formal Georgian doorway, and returned to put a similar doorway on his home.”

Connected to this three-bay mass is a two-bay section—the home’s first “addition.” The materials are consistent with the main section, suggesting it followed by a decade or two. The wall is set back a few feet, and the roofline is lower for proper scaling. From here, the home turns the corner in both directions (the T), and as it does so, it enters a new century.

At this transition, the architects faced a challenge. In order to create the illusion that the two perpendicular wings were not designed at the same time (“the hard thing is designing a house that doesn’t look designed”), Zimmerman “had to find some subtle way of turning the corner that fit with our story line.” The solution? Where the two wings meet, the roofline slants down to a single story, forming what looks like a small tacked-on shed—a shed that perhaps survived a renovation. It worked brilliantly, lowering the scale in the corner and making the entire transition look like a pragmatic choice made by that same farmer.

Throughout the house, the architects devised similar tricks for progressing with their narrative. For instance, they altered the grade of fieldstone and mortar joints from section to section. In the three-bay main entry, you find flat dressed stones, with big, beautiful rectangular stones climbing the corners in a sort of country quoining. Complementing this buttoned-up look are German V mortar joints, lightly brushed to make them look weathered. But in the more primitive wings are rubble stone jointed more haphazardly (on purpose, of course) with either a wide, flat brush pointing or a technique called barn dashing, which leaves stones spattered with traces of mortar. “In the past, farmers didn’t care so much about looks; they just wanted to make these things tight,” says Zimmerman. By contrast, “we treated the main mass as if the farmer had hired a mason to do the entire thing.”

Historical trimwork surrounds an arched doorway that leads to the living room.

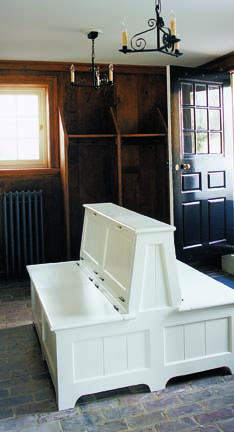

The team applied the same level of creativity to the interior detailing as well. They used a combination of antique and reproduction materials, such as early brass locksets and mirrored sconces in the main mass. But as you move into the “nineteenth-century additions,” you see more primitive wrought-iron hardware, not because these rooms—kitchen and informal dining room, mud room, bedrooms—are older but because they are more private. A similar progression from fancy to plain occurs in the wood floors, which begin as chestnut and oak in the living and dining rooms and transition to wide-plank pine in the lesser areas. In one transition between rooms, a stone sill stands between two different wood floors, like a ghost marking a forgotten exterior passageway.

Is this degree of detail really necessary? “The suspension of disbelief is only maintained if you really take it down to that level of detail and thought,” Zimmerman says. “We want the client to continue to discover things in the house-to have a greater understanding of what we’ve done—5 years, 10 years, 15 years down the road.”

In other words, even a new house can tell stories. Not with words, but with stone and wood and metal, with rooflines and wings. Never all at once, but spooled out slowly, over the years. And then someday the new house is an old house, with even more stories to tell.