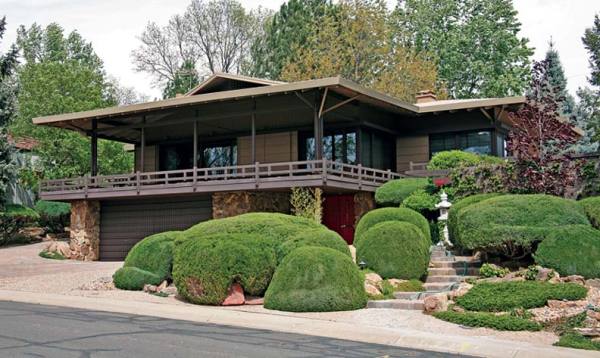

Many of the homes in Arapahoe Acres, like this bi-level design, are reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses.

Housing crisis? What housing crisis? Richard Rost was so eager to buy into Arapahoe Acres, a sparkling 1950s-modern suburb in Englewood, Colorado, that he waited two years. The community, located just south of Denver, is one of those fortunate spots that seems unscathed by the current housing meltdown. Houses here seldom hit the market, and when they do, there’s most often an eager buyer.

Yvonne and Dave Steers also were eager buyers in the Arapahoe community. The couple recently purchased their 1955 home within days of seeing it for the first time. Now Dave has made a second career of specializing in the rehabilitation and sensitive updating of ’50s-era vintage homes in his neighborhood and in other parts of Denver, finding and working with craftsmen to re-create missing pieces from the past.

It’s a point of local pride that Arapahoe Acres was the first 1950s housing development to win a place on the National Register of Historic Places. It achieved its status as a historic district in 1998, just five decades after the building project began and before the houses had attained the Register’s age criterion of 50 years.

The living room of Dave and Yvonne Steers’ house shows the typical openness of the interiors, with wide banks of floor-to-ceiling windows opening to a rear patio and screened porch.

The district contains 124 houses built between 1949 and 1957, carefully sited along winding streets. Although there are no sidewalks, the traffic-calming effect of the curving street pattern makes pedestrian travel safe and pleasant, encouraging homeowners to meet and greet their neighbors. Some of the residents are original owners; others, like the Steers and Rost, are relative newcomers, ardent mid-century modernists who are as passionate about the preservation of their homes’ authenticity as they are about their collections of ’50s furnishings.

Modern to the Core

Amidst miles of what critics have termed postwar ticky tacky, builder Edward B. Hawkins envisioned a loftier undertaking. In 1949 Hawkins purchased 30 acres of mountain-ringed land in Arapahoe County. He hired a talented young architect, Eugene Sternberg, a professor at the newly created University of Denver School of Architecture and Planning, to design the new development and create a series of houses for it.

Founded by Carl Feiss, a nationally prominent planner and a leader in the postwar modern movement, the school held special promise for Sternberg. A native of Czechoslovakia, he had immigrated to England, where he taught at Cambridge University during the war before moving to the United States. Like many architects of his era—including such luminaries as Frank Lloyd Wright, Marcel Breuer, and Walter Gropius—Eugene Sternberg yearned to design small, low-cost, yet beautiful and functional homes.

Richard Rost’s unusual 1957 split-level has wide overhangs and a balcony under a low gable roof.

Hawkins, on the other hand, was more interested in building individualistic, custom-designed houses for a more upscale market. The first 20 Arapahoe Acres houses were built to Sternberg’s designs before the developer and the architect parted company, but Sternberg’s fluid layout for Arapahoe Acres continued to form the backdrop for the homes that followed his departure.

While other Western developers tended to flatten sites to uniform levels and employ more economy-minded rectangular street layouts, Sternberg’s forward-looking plan favored irregular setbacks and siting in order to accommodate terrain, views, and privacy needs. Rolling land was kept as a design asset, and the houses were often angled rather than parallel to the street. (And yes, even then it wasn’t easy to get an unorthodox site plan past the regulators.) Spacious front yards and private back yards provided ample room for landscaping, including some specimen trees and other plantings provided by Hawkins himself.

After Sternberg left the firm, Hawkins, who was trained as an engineer, served as his own designer. As a young man, he had worked in construction in Chicago, where he was profoundly impressed by the domestic architecture of the Prairie School and particularly by the works of its leader, Frank Lloyd Wright. Hawkins’ houses reflect those early influences. In 1951 Hawkins hired architect Joseph G. Dion as his assistant, and together Dion and Hawkins continued Arapahoe Acres’ modern emphasis.

Developer Edward Hawkins designed many Arapahoe houses, including this one built for his own family. Inspired by a trip to Japan, the home recalls traditional Japanese house construction and landscaping. The two-car garage, however, is strictly mid-century American.

Pitching the Product

Hawkins, a tireless promoter, won the sponsorship of Revere Copper for his first houses by making generous use of copper inside and out. He also built two Better Homes and Gardens display houses in Arapahoe Acres (1954’s Home for All Americans and 1955’s Idea Home). Interestingly enough, Eugene Sternberg designed the magazine’s 1951 Five-Star Home—a design very similar to his Arapahoe houses.

Most of the houses in the development exemplify what we call Soft Modern—clean, modern design without the hard-edged purity of the glass-and-steel International Style. Exposed structure on the interior, natural materials, sloping roofs, and informal floor plans all supply a measure of warmth to the buildings. Although some concepts from both the International Style and Wrightian design are echoed in Arapahoe Acres—particularly in the individualistic houses designed by Hawkins—most of the homes are contemporary, approachable, easy on the eye, and easy to live in, fitting comfortably within the mainstream of postwar, somewhat upscale modern development.

Like many Arapahoe Acres homeowners, Richard Rost is an avid collector of mid-century furniture.

Relatively small by today’s standards, the houses were either one or two stories, with an occasional split-level. They had flat or low-sloped gabled roofs, even the occasional exotic “butterfly” roof (a low, irregular V-shape). Massive chimneys punctuated the rooflines. Building materials included red or salmon brick laid in Roman or standard bond, concrete block, plywood panels and board-and-batten wood siding. Entry doors were discreetly placed, sometimes located on the side of the house rather than on the front. Attached garages and carports were a nod to the mid-20th century’s love affair with the automobile.

On the interior, open floor plans led through sliding glass doors to small paved terraces or patios and screened porches at the rear. Kitchens also were placed at the rear of the house, separate but open to the dining and living rooms and conveniently near the outdoor living spaces.

High ceilings, ample window walls, and clerestory windows made small rooms seem spacious and well-lit. Philippine mahogany wall panels and floor-to-ceiling closet doors graced the rooms. Easy-care asphalt tile or cork flooring was used throughout the houses. Prominent large fireplaces dominated the living rooms.

Although many—possibly most—of Arapahoe Acres’ houses have undergone interior renovations, and some have received additions and alterations, the changes have—so far, at least—been remarkably few and blessedly inoffensive. In fact, Arapahoe Acres may be in a bit of a time warp—and that’s just fine with the folks who live there.