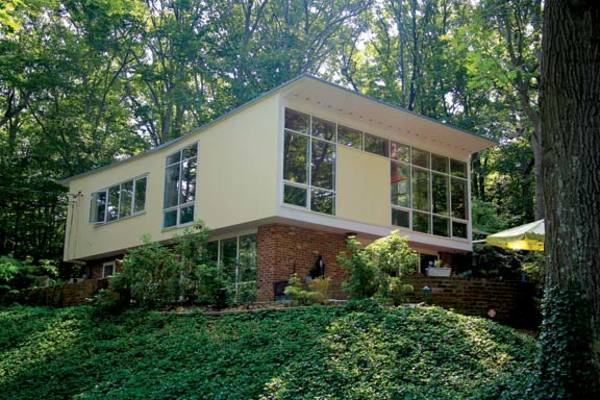

These Rebecca Drive houses enjoy dramatic views through the trees while preserving the privacy cherished by Hollin Hills residents.

Looking for a woody escape from the urban hustle? A secluded spot where birds sing and squirrels frolic and Mother Nature never seems to shake an angry finger in your face? Not some lonesome cabin on a way-out mountainside, but a year-round kind of place, close to jobs and schools and civilization yet really, really special?

We know the perfect spot. It’s Hollin Hills, a close-knit neighborhood of some 400 glass-enclosed minor masterpieces by one of the leaders of America’s postwar Modern movement.

This backyard wilderness is located about 10 miles from the nation’s capital and within biking distance of George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Despite its historic surroundings, Hollin Hills has been attracting residents with an architecturally progressive bent for 60 years.

Creative Vision

Hollin Hills was the brainchild of Robert C. Davenport, a Department of Agriculture employee who came to Washington from Nebraska in 1938, at the peak of FDR’s New Deal. After World War II, he became a successful merchant-builder in the Virginia suburbs as a sideline to his government day job.

Davenport had a vision for Hollin Hills, and he also had the ability to assemble the raw materials, funding, and creative cast of characters needed to bring his vision to life. The land he chose in 1946 was hilly, with meandering creeks, steep slopes, difficult building sites, no utilities, and no roads. For most developers, that combination would have spelled disaster. For Davenport, it looked like destiny on his doorstep.

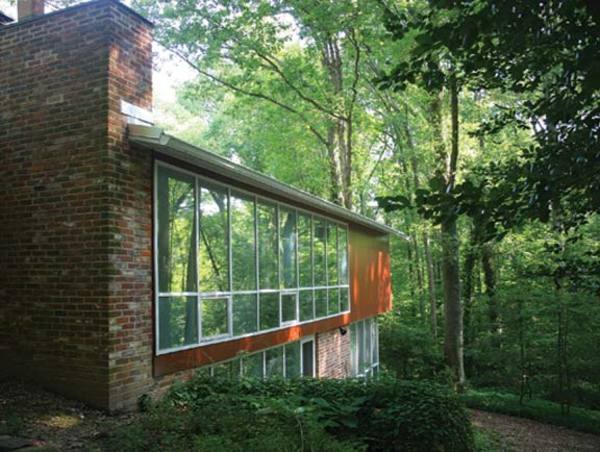

Houses with inverted “butterfly” roofs were among Charles Goodman’s most distinctive designs, offering expansive interior space with a wide view from the frame upper floor that oversails a brick ground floor.

He picked a well-known architect, Charles M. Goodman, whose experience in government and military building had taught him to use prefabrication and modular construction with wit and economy; a landscape architect, Lou Bernard Voigt, who had an aversion to fences and walls; and a skilled and exceptionally patient construction foreman named Mac McCalley. And, in that house-hungry postwar decade, Davenport knew he could count on a host of eager buyers.

Construction began in 1949 and continued until 1970. Goodman’s last design was in 1961; in the later period, Davenport contributed some of his own house designs, which were similar in tone to Goodman’s. After Voigt’s death in 1953, landscape planning fell to Dan Kiley, a noted classical modernist, and, later still, to Eric Paepcke. Both continued to emphasize a seamless flow between indoors and outdoors and from property to property. For an extra $100, homeowners were offered planting schemes created specifically for their lots.

Planning the Community

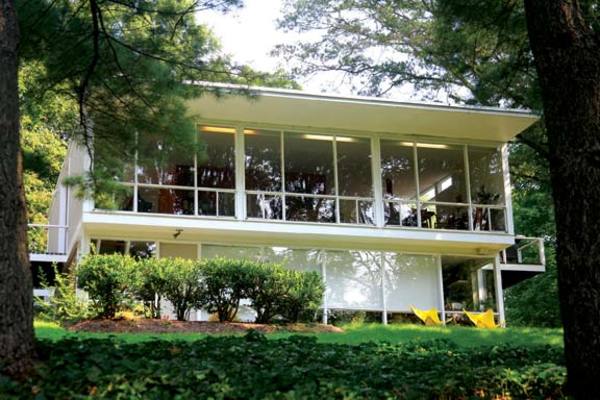

Like this one, many Hollin Hills houses are artfully set on steep grades, becoming a full two stories at the lower end.

Davenport was determined to interfere as little as possible with the irregular terrain and natural vegetation of the land. Accordingly, Goodman laid out the new community with curving roads that yielded to the existing topography and set aside ample space for parklands and walking trails.

Goodman devised several affordable but distinctive house plans that could be adapted to suit the needs of individual homeowners—mostly married couples with children—while capitalizing on Hollin Hills’ quirky 1⁄3 – to ½-acre building lots. Goodman’s models were endlessly varied in size, plan, elevation, and roof type, thus artfully skirting any suggestion of a cookie-cutter community.

Focusing on privacy, views, and solar orientation, Goodman ignored convention when placing houses on their lots. There were no uniform setbacks and no head-on confrontations with the street. In fact, most Hollin Hills homes seem to look backward or sideways—in any direction except into their neighbors’ windows and yards.

Though Goodman’s designs aren’t derivative, they show some influence from both Frank Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra. Based on fixed modules that changed over the years, they were crisp without being sharp, simple but not austere—they might best be described as Soft Modern. Interestingly, for a remote suburb of the automobile-dependent postwar era, Hollin Hills paid scant attention to the demands of the car. There are some carports, but garages are notably absent.

Top Models

The first house plan Goodman offered in Hollin Hills was a split-level, a newly popular house type proven particularly suitable for sloping sites. Although the split-level had been introduced in the 1930s in the Chicago area, the Depression and war years had delayed its national spread until after wartime shortages eased. In the early 1950s it found fans throughout the Northeast, and Goodman deftly exploited its qualities for Hollin Hills. With entry, living, and sleeping areas each on a different floor, the split-level required fairly constant movement between levels, but it perfectly suited the open interior spaces and large window areas that characterize Hollins Hills houses.

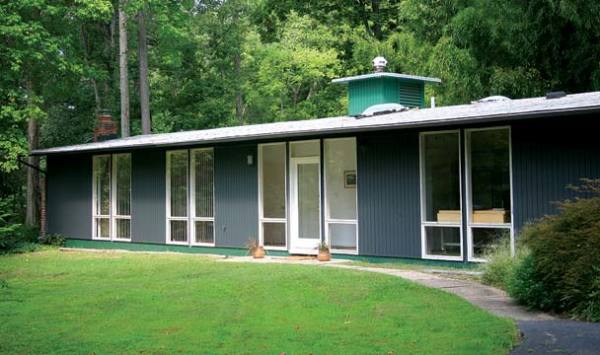

This later design with a flat roof and a deep overhang retains the characteristic window wall looking out over its steep lot.

Another of Goodman’s initial designs was a small, undecorated, flat-roofed slab-on-grade rectangle with three bedrooms and one bath. Like many early ’50s houses, its living, dining, and kitchen spaces were minimally differentiated, and it maximized the perception of spaciousness by giving visual access to the outside. Yet it was a far cry from the ubiquitous shoebox spec houses of the era.

In Goodman’s version, frame walls with vertical wood siding were lifted out of the ordinary by massive brick chimneys and fireplace walls and long stretches of what are now known as “Hollin Hills windows” across the width of the house.

The strong appeal of this design comes from the intimacy with the outdoors created by glass window walls looking out to a verdant landscape.

The third major plan was for a larger, two-story house with an oversailing second floor projecting over otherwise unusable sloping land, thus creating interior space out of thin air. These projections have a sheltering effect for the first-floor windows beneath and create the opportunity for great views.

Materials were simple. Salvaged brick enlivened many of the exterior (and interior) walls, chimneys, and fireplaces; it was later replaced by painted CMU (cement block). Vertically grooved wood panels and horizontal windows created the celebrated 1950s cross axis of a strong vertical architectural element intersecting a horizontal one.

All of the plans had several variations, and were designed to be easily enlarged, generally by lengthening. Using prefabricated roof trusses with spans identical to the original house for these extensions was a labor-saving practice that was economical as well.

Hollin Hills Today

Attic fans (evidenced today by cubical “cupolas”) encouraged airflow through the house.

Even large Hollin Hills houses are fairly small by today’s standards. Goodman’s designs recognized the inclination to grow, however, and through the years, residents have been uncommonly respectful of their homes’ original architecture and their neighbors’ privacy. Consequently, although the community now has few completely unaltered houses, additions tend to be well-designed—thoughtful, attractive, and complementary to the original building fabric.

Of the 463 houses in the proposed Hollin Hills National Register district, surveyors identified only a handful that could be called (in Register parlance) “noncontributing resources” because of alterations. Most were disqualified on the basis of size rather than design.

From the beginning, Hollin Hills has been distinguished as much by its sense of community as its forward-looking architecture and remarkable landscape. As professional preservationist and longtime resident Jere Gibber notes, “First and foremost, Hollin Hills is an amazing community.”

That’s exactly what Davenport, Goodman, and Voigt imagined so many decades ago.