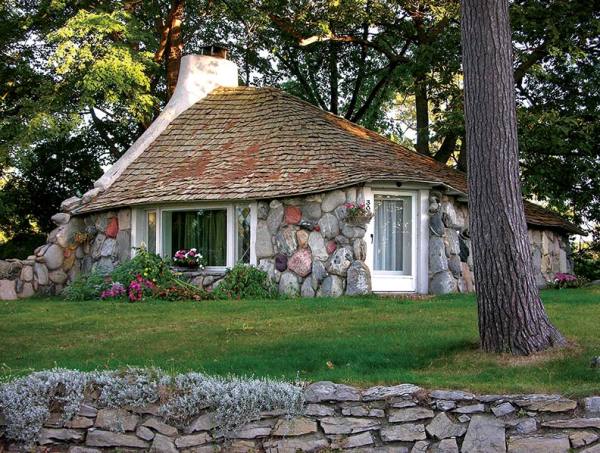

The Half House is Young’s smallest creation. Composed almost entirely of granite boulders and local fieldstone, the cottage appears to have sprung up from the ground.

“I’ve got just the house for you,” the man said. It was February 1995, and I was at the Grove Park Inn Arts & Crafts Conference, chatting with a fellow attendee about the warmth and down-to-earth appeal of bungalows, and my own predilection for all things whimsical. The man went on to describe a tiny town called Charlevoix on the tip of Michigan’s lower peninsula, which boasts a unique collection of stone homes known as “mushroom houses.” The houses, he told me, were designed by one Earl Young, a diminutive local builder whose architectural creations seem to erupt straight out of the ground; a few of the homes even have curved, undulating roofs that bear a remarkable resemblance to mushroom caps. My interest was piqued—I had to know more.

A Mushroom Patch Is Born

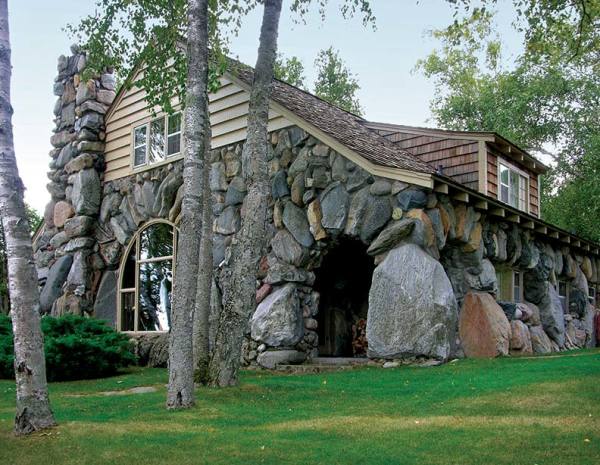

In 1924, Earl Young purchased 37 1/2 acres of land in Charlevoix called Bartholomew’s Boulder Park, named for the abundant glacier-buffed boulders deposited into the land centuries before. The centerpiece and gateway to Boulder Park is Boulder Manor, a plus-sized home built from plus-sized boulders that Young started in 1928. Construction was halted due to the looming Great Depression in 1929, and Boulder Manor wasn’t completed until the late 1930s.

Boulder Manor, begun in 1928 but not finished until the late 1930s, welcomes visitors to Boulder Park.

The building is a jumble of boulders of different sizes and colors, collected from the surrounding countryside. The front entry, which resembles a cave, is flanked by giant boulders. To the left of the entryway is a massive chimney and fireplace, and a large parabola-shaped window that looks out on Lake Michigan. It appears that much of the landscaping was designed around the boulders on the property, but in fact, Young meticulously placed the boulders to make it seem like they just happened to be there. A children’s playhouse, complete with working fireplace, crowns the landscaping theme. It was built years before Boulder Manor was finished so Young’s children could play while he worked on the house.

The Norman Panama House, one of Young’s larger creations, was built circa 1930. It was commissioned by Herman Panama, but named after his son, Norman, a celebrated screenwriter, producer, and director who worked with Hollywood legends like Fred Astaire, Cary Grant, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope. Local legend holds that Norman spent many summers writing at the house, and the texture of the house and surrounding area influenced many of his screenplays, most notably 1948’s Mr. Blanding Builds His Dream House and 1954’s White Christmas. A few steps away from the main house is a whimsical guest house that originally served as a garage and is now a summer cottage.

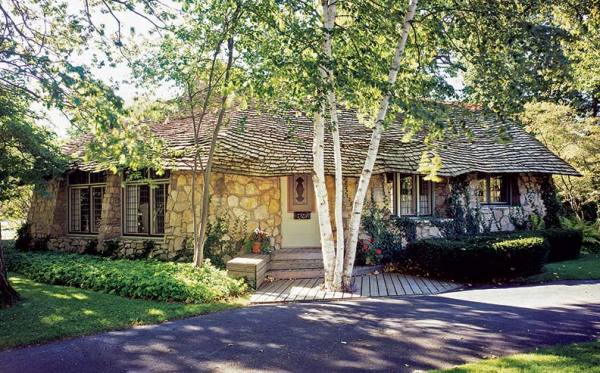

The house Earl Young built for himself and his wife, Irene, in 1946-47 is one of his more restrained creations. The horizontality of this elevation (seen from the other side, it’s a two-story house) echoes the California ranch style, which was popular at the time.

Young’s two finest examples of mushroom houses, as well as the home he built for his family, are not in Boulder Park, but rather on a little triangle of land close to downtown Charlevoix. Young constructed seven of the homes within the Park Avenue Triangle, and remodeled three. The most diminutive cottage is known as the Half House because of its cut-off shape. Constructed in 1947, it is composed almost entirely of boulders and local fieldstone and is capped with a wavy, cedar-shingled roof.

The most well-known mushroom house, the one that inspired the moniker, rests largely on the foundation of an old farmhouse. In fact, some of the timbers from the original farmhouse were incorporated into the design of the Mushroom House. However, the walls of the house, some of which are more than 3′ thick, support the entire structure.

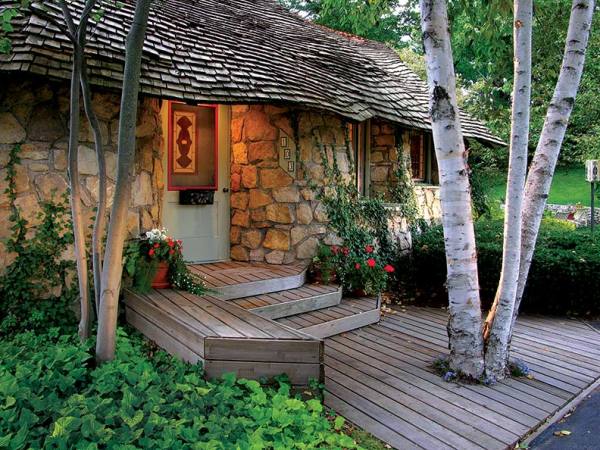

Young’s entryways were not grand, as this 1950s example demonstrates. Rather, they’re set into the home and blend into the organic construction.

The footprint of the house is an undulating oval, and it’s crowned with an equally rippling cedar shake roof. When Young constructed the roof, he propped up the beams with pieces of wood—including doors complete with doorknobs—from the old farmhouse. Details of the construction were revealed when the old roof, which had been constructed with 18 layers of randomly cut shingles, was replaced with a mere four layers of uniform-cut shingles in the early 1980s.

Architectural Influences

Mushroom houses are a unique brand of vernacular architecture that doesn’t fit neatly into any one architectural style. However, like most architects and builders, Young’s creations were influenced by other dominant styles of the time. The Arts & Crafts movement, with its emphasis on handcrafted material and exposing the “bones” of a structure, is clearly visible in mushroom houses. Young’s mushroom houses, and other local homes influenced by them, are often decorated with Arts & Crafts-style furniture and lighting, which harmonizes well with the woodsy, organic charm of the stone houses.

This massive fireplace is the centerpiece of one of Young’s Boulder Park homes. To soften the sharp angles of the stones, the main body of the fireplace is constructed in a semicircular shape.

Young primarily let the landscape dictate the design of his houses, an aesthetic championed by his contemporary, Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright, of course, was a trained architect, while Young had little formal architectural training. Rather than work with complex blueprints and drawings, Young preferred to walk around a site, pacing out rooms and noting the location of trees and boulders, writing his instructions to carpenters and stonemasons on scraps of paper. The stage set, Young then proceeded to address the finer points of the design.

Young took his design cues from the area’s copious boulders. He believed the boulders had distinct personalities, and he wanted certain boulders placed in ways that would reflect their character. Sometimes when a boulder didn’t rest quite the way Young wanted it to, he would suspend it from a crane, apply mortar underneath it, and leave the crane in position until the mortar had sufficiently dried. He was also known to have squirreled away peculiar boulders by burying them and marking the location, unearthing them when he was ready to embark on another construction.

Another strong architectural influence woven into the fabric of mushroom houses is the Storybook Style, a type of architecture that gained popularity in the 1920s. Storybook Style architecture mimics rural European vernacular architecture and often uses found or recycled material, or carefully weathered new material. Young’s designs often employed driftwood that washed up on the shores of Lake Michigan, salvaged leaded glass windows, and old street lamps.

The pinnacle of Storybook Style is embodied in the wavy roofs that appeared on Young’s most notable houses. These undulating extravaganzas were created by connecting uneven rafters with lathe or sheathing, then applying multiple layers of cedar shakes. The eaves of these homes hover just above the ground, and the front entries feel more like portals than porches. Another Storybook Style feature often employed by Young is the squat, cartoonish chimney that appears to be sagging and dripping with gingerbread-house frosting.

The eponymous Mushroom House is Young’s most noted creation, its rounded shape and undulating roof reminiscent of a button mushroom.

Young’s consummate mushroom houses were constructed some years after the Storybook Style had waned in the U.S., suggesting he picked up his design and construction cues from magazines and from his trips to Europe, where he saw examples of vernacular cottage architecture. (On one trip, he even purchased a thatched roof in England and had it shipped to Charlevoix in pieces.)

Fungus Fixes

Like their counterparts in the vegetable world, mushroom houses are not without their problems. Married for more than 60 years, Earl Young apparently didn’t find the need to spend much time in the kitchen, and his lack of knowledge about the day-to-day activities in this realm of domesticity resulted in rooms of sparse proportions. As a result, almost all of his homes have had significant kitchen remodels.

The deeply set entryway of the Mushroom House is one of Young’s trademarks. The height of the entry, which barely extends above the door, is typical of the Storybook Style.

His signature serpentine cedar shake roofs, while beguiling to the eye, also attract and trap water and debris, resulting in problems with fungus, mold, and rot. When owner Jeannine Wallace replaced the roof of the Mushroom House in the early 1980s, the re-roofing cost more than she and her husband paid for the house in 1964. Masonry, if not periodically sealed and maintained, invites and traps water, which, combined with harsh Michigan winter freezes, can lead to cracks in the mortar and stone. In addition, almost all of Young’s homes were designed for summer use and weren’t equipped with any heat source other than the fireplace. Year-round homeowners have had to install modern heating systems, a job made much more complicated by the necessity of boring through limestone and granite.

Despite their problems, though, when these homes come up for sale in Charlevoix, they don’t stay on the market for long. It’s hard to resist the whimsical, simple charm of mushroom houses—although it can be hard to pin down, it’s the type of architecture that’s guaranteed to make you smile.

Writer and photographer Douglas Keister has authored or co-authored 27 books on historic residential architecture.