Toronto architect Wayne Swadron blends English and French country touches with rural vernacular Ontario architecture to create a new old country house for Robert and Robin Ogilvie on 116-acre Coffey Creek Farm.

The best new old houses are not those that evoke another place and time but that anchor us in the present. A new old house that reminds us of a real or imagined past is little more than a stage set, leaving us with a naggingly uncomfortable, disembodied Disneyland feeling. An authentic new old house summons the opposite emotional response: It somehow feels just right, enveloping us in a warm embrace, as though it has always been there, as though nothing else could possibly be better.

Authenticity is an illusive attribute of traditional building, one that can slip from the grasp of even the most committed client and the most talented designers. When Robert and Robin Ogilvie set out 12 years ago to find a weekend home in the countryside north of Toronto, nostalgia and romanticism were their initial driving forces: nostalgia for childhood visits to Robin’s grandparents’ farm in the same Caledon area coupled with romantic notions of English and French country houses.

The canvas they chose to fulfill their dreams was the 116-acre Coffey Creek Farm, named for the family that first tamed the land at the turn of the twentieth century. The Ogilvies quickly decided to clear their canvas of an uninspired circa 1970 farmhouse, leaving behind a bucolic landscape of rolling hills and original 1904 barns with their stone foundations. A legacy of their immediate owner-predecessors that the Ogilvies retained, however, was the thousands of trees that had been planted in a picturesque fashion, which helped shape and define the natural landscape of rolling meadows.

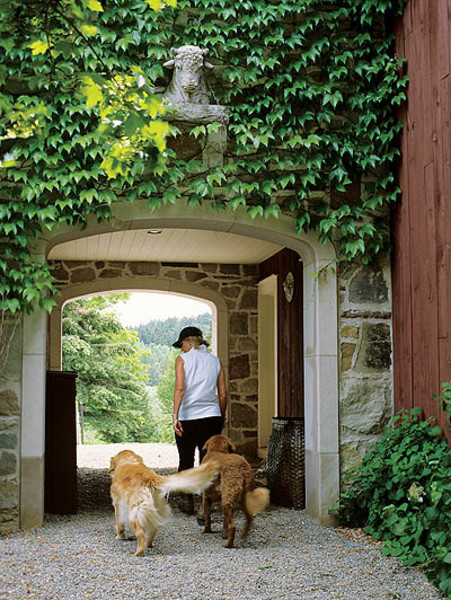

Toronto architect Wayne Swadron blends English and French country touches with rural vernacular Ontario architecture to create a new old country house for Robert and Robin Ogilvie on 116-acre Coffey Creek Farm. The Ogilvies’ canines rest on the stoop of the main portion of the house, a stone structure covered in ivy that contains the formal rooms of the home. Note the board-and-batten shutters—a common element on the region’s farmhouses.

The Ogilvies turned to interior designer Sharon Mimran and architect Wayne Swadron, both of Toronto, to help them turn their dreams into reality. Eagerly responding to the challenge, Swadron set to work blending English and French country motifs with rural vernacular Ontario architecture in an entirely new country house. Heavy timber and stone, left exposed or finished in stucco, are prominent both inside and out, materials that are equally at home in Brittany, the Cotswolds, and the Canadian countryside. The plan of the house is organized into three distinct volumes that embrace a gravel entrance courtyard, lightly landscaped at the edges by landscape artist Curr Didrichsons with shrubs and ivy that now completely covers the stone front of the main part of the house.

Simple entry courts like these are among the defining elements of European country houses, whether English, French, or Austrian, and play an important role in creating a sense of place in an otherwise boundless rural landscape. Much like a fireplace hearth in a large room, a courtyard becomes a focal point, both inside and out, that establishes a comforting human scale and defines the relationship with the broader landscape.

A stone-arched breezeway connects another two-story wing to the main house.

The three volumes of the house give the impression of having been built at three different times, but this is less of an artful deception than a time-tested design strategy. The main volume is a simple two-story stone-clad rectangle with a central front door, about which windows are symmetrically arranged, and a simple gable roof bracketed by massive chimneys at either end: the archetypal sturdy and practical English country house. As one might expect, this part of the house contains an entry hall (with a dignified but elegantly restrained staircase) and the formal living and dining rooms. To the left of the entry court is a hipped roof, single-story wing that imparts a French provincial flavor.

In a French country home, one might expect to find the stables here, but this wing instead houses a master bedroom suite, as well as an intimate family room and kitchen where the wing meets the main house. When the Ogilvies are in residence alone, without their now-adult children or guests, this wing becomes a self-contained dwelling unit.

To the right of the entry court, another two-story wing is separated from the main house by a stone-arched breezeway. This wood-clad wing is a literal interpretation of a vernacular Ontario red barn that very successfully tempers any European pretensions that might otherwise gain an upper hand. Had this wing been designed to match the rest of the house more closely, the delicate balance between authenticity and artifice might have tipped dangerously toward the latter. The Caledon area of Ontario is neither Provence nor the Cotswolds, after all, and this barn wing lets us know exactly where we are.

Inside, the house has the comforting ambience that one would expect to find in a country home. Wide-plank floors, heavy-timbered ceilings, and exposed exterior stone walls contrast with whitewashed plaster walls that provide the backdrop for an eclectic mix of sturdy country furniture seemingly collected over time. The well-appointed kitchen and bathrooms remind us that form followed function in a very practical way long before the catchphrase became a tenet of modernism, while a glass-enclosed conservatory and two comfortable parlors—the living room and family room—remind us that country life is civilized life, as much a place for tea and politics as for crops and animals.

The things that one touches every day hold the key to authenticity in a new old house. Swadron and Mimran carefully selected or designed every tactile detail. There is very little to distinguish fireplace mantels, wood cabinetry, bathroom finishes, hinges and handles, or Dutch doors from their nineteenth-century predecessors. According to the architect, all primary building materials, including stone, heavy timber framing and lintels, wood siding, even the entry court gravel, were either reclaimed or quarried from sources within 5 miles of the building site. “This was very purposeful,” says Swadron. “We wanted the home to feel as though it could have been constructed on the property by original settlers using materials that would have been readily available to them at the time.” Craftsmen such as stone masons, metalsmiths, and timbersmiths were enlisted to create an authentic feeling of age and to ensure that no aspect of the finishes would reveal the home’s true age. Swadron views this not so much as false deception as a form of “genuine accelerated aging.” Ten years after it was completed, Swadron notes with satisfaction that “the house is aging wonderfully; it’s carrying on the aging process that we left it with. It’s a special place that has its own heartbeat.”

The house that began as a dream quickly became a way of life. Though it was not part of any original master plan, as Coffey Creek Farm began to take shape, the Ogilvies realized that it would become their home, not just a weekend retreat. That allowed Robin Ogilvie to begin thinking seriously about another lifelong dream: raising horses. Today, Coffey Creek Farm is a widely recognized and highly regarded registered horse breeding and training facility devoted to the Rocky Mountain and Kentucky Walker horses. But most of all, it is a place that expresses the character of the people who built it, a warm and welcoming environment that transports visitors to a different state of mind, removed from the hustle and bustle of the modern world.

Though it was designed 12 years ago and completed 10 years ago, Coffey Creek Farm remains one of Swadron’s favorite projects. “Every member of the team, especially the clients, were appreciative, generous, patient, and enthusiastic,” he recently recalled. “Projects that have clients like that are always the best projects in the end, and we end up working so much harder for them.”

Michael Tardif is the editor of Architecture D.C. and a freelance writer living in Bethesda, Maryland.