Donald Weggeman and Odel Childress in front of their 1906 Hollywood Craftsman.

There was a murder in the bathroom, and the furtive killer made only one mistake—he forgot to clean the light switch. “It smells like your bathroom…like bleach,” Natalie tells Monk, the loveable detective who suffers from a touch of obsessive-compulsive disorder on the eponymous series. Natalie, Monk’s personal assistant, is snooping around the house looking for clues while Monk, in bed with a fever, coaches her over the phone. “Is there blood?” Monk asks. “Switch on the light.”

Natalie flips on the light, revealing a single red fingerprint. “It’s blood.”

“Oh yeah,” Monk says with a note of satisfaction. “They always forget the light switch.”

Hollywood was likely the furthest thing from their minds when Donald Weggeman and Odel Childress bought their 1906 Craftsman house in Los Angeles’ Harvard Heights neighborhood in 1984. The couple was looking for a historic property, and their real-estate agent sniffed out the house before it was listed. “We loved the house and offered them the asking price of $135,000. We’ve been here ever since,” Donald says.

For a house almost eight decades old, it was in remarkably good shape. “So many homes in the neighborhood had been turned into boarding houses, with their entire footprints altered, but we bought ours from its second owners,” Donald explains. “The old man we bought it from was sort of a curmudgeon. He didn’t put any money into the place.”

Years of neglect actually worked in Donald and Odel’s favor: In all that time, the previous owners hadn’t painted over the woodwork or renovated the kitchen. It was period-perfect. “We were very lucky,” Odel, the handy one of the pair, says. “The earthquakes from the ’30s and ’70s messed up a lot of plaster, so I had to teach myself plastering. But beyond that, there wasn’t a lot to repair.”

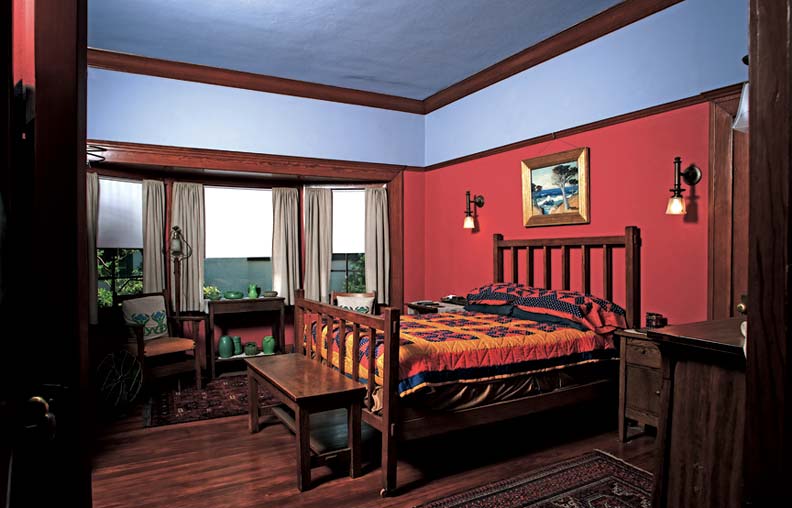

Constructed in 1906 by Hudson and Munsell, a prominent local architectural team who designed the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, the house is 4,200 square feet, with six bedrooms and about 400 square feet of converted attic space. Records show it cost approximately $6,000 to build. With almost all the original light fixtures, keyhole compartments in the library desk, and built-ins that include library bookshelves, bedroom closets, and a dresser in the bathroom, the home boasts a plethora of original Craftsman details.

While scraping wallpaper off the living room walls one day, Odel found remnants of an original frieze, an oak leaf pattern. He sent the sample to Bradbury & Bradbury, the famed wallpaper firm, and the company reproduced it from the tracing. “They gave us enough to do our frieze,” Donald says. “We were fortunate; you’d have to be Mount Vernon with a federal budget to create an original like that.”

Nothing but the Real Thing

While removing layers of wallpaper from the living room walls, Odel uncovered remnants of an original frieze from 1906. The distinctive oak-leaf pattern was re-created from the sample.

Their first two years in the house, Odel made plans to freshen the plaster and do some repainting, but he quickly put those aside in favor of antique shopping. “Barbra Streisand had just made her famous purchase of the Gustav Stickley sideboard, and I thought, ‘Now the prices are going to skyrocket,'” Odel says. “So I dropped my paintbrushes and trowels for a year and went shopping.”

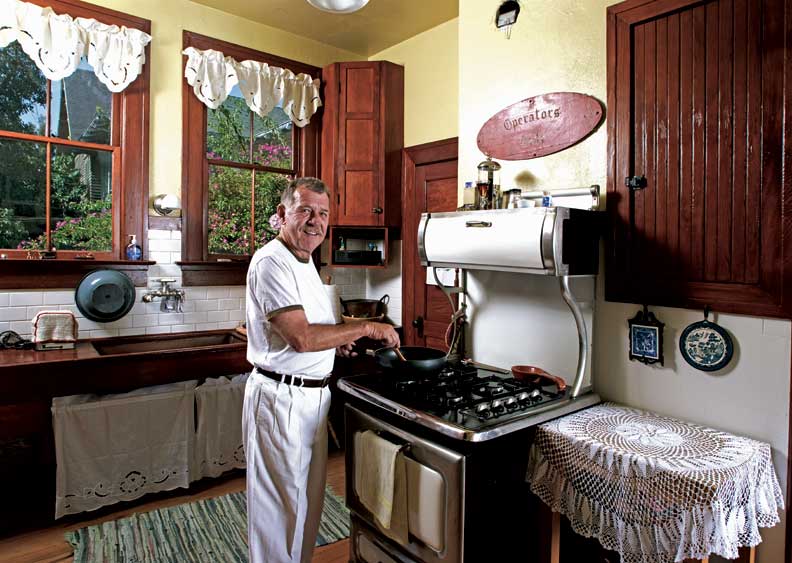

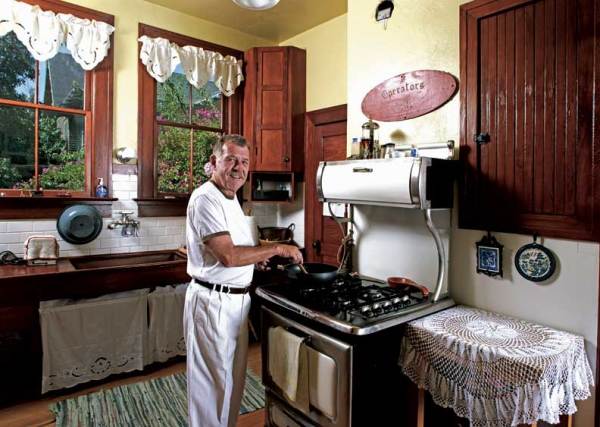

Odel and Donald traveled the country hunting antiques in mom-and-pop stores, an effort that resulted in such finds as an antique umbrella stand (mistakenly sold upside down as a fern stand), a floor lamp that turned out to be an original Gustav Stickley, and a 1914 A.B. Battle Creek gas stove, which Donald cooked on for 20 years until they restored the kitchen and added a new reproduction stove. Four years ago they completely refurbished the kitchen, retaining the wood countertops and hiding the refrigerator and dishwasher in a butler’s pantry. “Odel said, ‘People will ask where the island is.’ There’s no place for an island in a 1906 kitchen,” explains Donald.

“We have a sort of museum, which means there isn’t a comfortable couch in the house,” Donald jokes. “We’re used to it, and we’re willing to make that sacrifice for authenticity’s sake.”

In fact, the only furniture not original to the period are pieces that hide technology. A Victorian cabinet originally used to store sheet music conceals the stereo system, and Craftsman-style armoires hide the television and computer. “You would never even know we have such modern things in our house,” Donald says.

Hollywood Comes Knocking

Harvard Heights is a popular neighborhood among location scouts, who look for out-of-the-studio places to film movies, TV shows, and commercials, and it didn’t take them long to come knocking on Odel and Donald’s door. Eager and excited, the couple signed with a neighbor for representation and put their house to work. In addition to serving as a killer’s house in Monk, the house has been in three or four independent productions, several commercials, and the opening sequence of horror flick Boogeyman II. (“Quite a distinction,” Odel laughs.)

The simplicty and elegance of the California Craftsman style is embodied in the home’s guest bath and its original, expansive built-in dresser.

Ironically, it wasn’t their meticulous attention to Craftsman detail that landed Donald and Odel’s abode in the Hollywood spotlight—in fact, when scenes are filmed there, the carefully collected antiques are carted out and replaced with replicas. “In one amusing filming, they moved all of our stuff out and brought their own Craftsman-style furniture in,” Donald recalls. “They didn’t want to take any chances with our good stuff, so they used modern reproductions from the studio’s prop department.”

The reason scouts clamor for the house is for specific architectural features that lend themselves well to film. (For example, in the Monk episode, the bathroom had four doors and plenty of filming angles.) In one infamous battery commercial, a man is uncomfortably situated in an easy chair with his neck in a brace and both legs in casts. When his wife goes out, he turns the television station to something a little risque, only to have her unexpectedly return with his priest in tow. The man frantically tries to change the channel as his wife and priest advance, in slow motion, down the hall, but alas—the batteries in his remote are dead. The reason Donald and Odel’s house was chosen? “We have a long central hallway with rooms opening up on both sides,” Donald explains.

Odel likens the filming process to redoing a room: “There’s junk all over the place, you’re crawling and stepping all over stuff, they’re moving furniture around, and everything gets jumbled.” But he loves it. “Everyone gathers in the ‘video village,’ and they include the homeowners, so it’s like having 50 new friends for a week. Plus, there’s free food. These movie crews just eat and eat.”

Even when the house is completely turned upside down—like when Odel’s 1892 piano was in the way, and movie crews paid to dismantle and store it during filming, then put it back together and tune it afterwards—Donald and Odel take solace in the ensuing paycheck. One day of filming can pull in $2,000, with another $1,000 for the strike (tearing down the set). “At that rate, one shoot can earn enough money to redo another bedroom. The house is working to pay itself off,” Donald says.

Preserving History

After 20 years of cooking on a 1914 A.B. Battle Creek stove, Donald succumbed to a modern reproduction.

Now that the restoration and furnishing process is nearly complete, Donald and Odel are busy with a related project: nominating the house for historic-cultural monument designation in the city of Los Angeles. Harvard Heights is now a Historic Preservation Overlay Zone, but for years the once-grand neighborhood was in danger of falling apart. It’s a familiar story: “We bought at perhaps the low point for the neighborhood in 1984, but we figured these houses were so splendid they were bound to turn around,” Donald says. The overall population was old and largely African American as whites migrated to the suburbs, the freeway bisected the neighborhood, and most of the homes had been converted into apartments. Donald and Odel were distraught to see their neighbors making significant and inappropriate architectural changes to the homes. “We watched as they stuccoed their houses and replaced double-hung, wood-clad windows with aluminum. For a while, we thought we’d made a mistake,” Donald admits.

“We hoped the neighborhood would improve, but we went through a fairly deep recession in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Then the riots of 1992 caused a lot of destruction through our business corridor,” he adds.

The neighborhood’s long-anticipated renaissance took place in the late ’90s. As Los Angeles commutes got longer and longer, white-collar professionals began moving back into the city. Odel, who was president of the neighborhood association, started pushing for a historic designation, but the city councilman wasn’t sold on the idea. “He didn’t like all the trendy newcomers trying to change things, but finally he gave in and got us the HPOZ status,” Odel says. (Since Donald is Caucasian and Odel is African American, Donald credits his partner with building a bridge between the new residents and the old.)

The episode of Monk that features Donald and Odel’s house reflects the neighborhood’s newfound gentility. In real life, the home’s occupants are happily retired—Odel from a career as a ceramics teacher and Donald from the publishing business. Though they enjoy parading their home on camera, it’s the real-life connection to the place that fuels their love for it. To them, filming is an adventure that takes place a week or two every year. The rest of the time, they’re proud to live in a period home that’s been their big project for the past quarter century. On screen or off, it’s a shining star.

Gretchen Roberts writes about food, homes, and gardens from her 108-year-old Craftsman-style house in Knoxville, Tennessee.