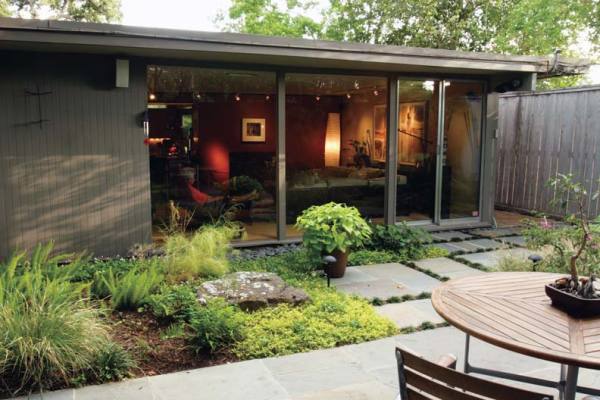

The suburban ranch house, born in Southern California, boasts simple, utilitarian designs. Regional variations typically involved the choice of building materials, with stucco and stone prevalent in the West and brick a staple in the East. (Photo: Tim Street-Porter)

The ranch house, that ubiquitous little rectangle that dominated suburban neighborhoods in the 1950s and 1960s, is no longer the new kid on the block. At more than 50 years old, it has finally come into architectural majority—in fact, it has more than reached the cutoff point for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

Perhaps that’s why architectural historians, ever hungry for a fresh debate on period styles, are scrutinizing thousands of unpretentious ranch houses built when Elvis was in his heyday. Granted, very few of these will make the Register on their individual merits. Most will be judged for their role as part of a historic district—as contributing resources, in official preservation parlance.

Each district might contain scores, hundreds, even thousands of houses that are no more imposing than—well, than the 1,000-square-foot “ranchburger” you grew up in, or the one your next-door neighbor tore down to build his 6,000-square-foot dream palace.

However, before you fall out of your La-Z-Boy laughing at the idea of a historic ranch house, take stock of where these fresh-faced houses came from, and what they’ve come to represent.

Home on the Ranch

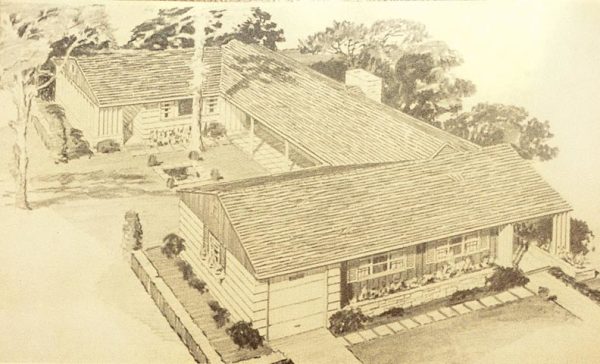

What exactly is a ranch house? With a little thought, most of us could probably tick off a list of ranch characteristics: one-story massing; horizontal lines; low-pitched gable or hip roof with overhanging eaves; a long, shallow front porch or, alternatively, a recessed entrance porch; an attached garage jutting out ahead of the main block of the house—and, oh yes, a picture window in the living room and sliding-glass patio doors at the rear. Even when the typical linear or L-shaped footprint is varied to become a U (or a V), we have no trouble picking up on the overall ranch-ness of the design.

The next question is, why on earth do we call this suburban phenomenon a ranch house? If the phrase “California ranch house” rings a bell, you’re on the right track. Southern California was indeed the birthplace of this now-familiar form—not just once, but twice. That’s where the ranch house first evolved in the early to mid-19th century, and that’s where the ranch was reborn a century later.

Patios offered refuge from the elements in new neighborhoods with few shade trees. (Photo: Courtesy of Atomic Ranch)

Of course, 19th-century ranch houses really were located on ranches. Rural dwellings, they were simple, linear, unadorned adobe or frame structures that were most often (though not always) a single story high and a room or two deep, with one or more porches extending across the long front façade and sometimes on the back or sides of the house. Such porches (called corredors) provided sheltered access to every room, avoiding space-eating interior hallways. They also enlarged the house’s living space while opening each room to outdoor light and cooling breezes.

The layout of the early ranch houses was informal and usually asymmetrical, paying more respect to function than to style. Need a room? Simply add one on. The rambling L- or U-shaped houses that resulted from this practical design approach were easily expandable, as well as winningly picturesque. Patios, partly enclosed by the walls of the Ls and Us, offered refuge from the region’s harsh sun and wind. They also afforded privacy and an element of protection from intruders.

Ranch Revival

In a very different time and setting, the 20th-century suburban ranch house also was informal and functional, attuned to the needs of growing families. In addition, it was inexpensive and quick to build, both vital considerations when the Baby Boom descended upon a housing market that had been stalled since the 1930s.

The idea of reviving the ranch house actually took shape long before the war. It first appeared mostly in the form of architect-designed, custom-built residences. Cliff May, a Los Angeles architect, is credited with having built the first modern-day ranch house in San Diego in 1932. May served as an architectural advisor to the influential Sunset magazine, which avidly promoted the ranch. In 1946, just in time to greet vets armed with G.I. Bill mortgages, the magazine published Western Ranch Houses, for which Cliff May contributed many of the designs. May wasn’t the only promoter of ranch design—many other architects, including San Francisco’s William Wurster, were intrigued by its possibilities—but it is May whose name has become inextricably linked with it.

Expanding the Ranch Range

Ranch house layouts were informal and asymmetrical. Function definitely trumped style, as the L- or U-shaped homes were easily expandable. (Illustration: James C. Massey Collection)

Of course, the ranch house craze didn’t end at the California state line. Developers and builders in every part of the country found the designs easy to sell to eager consumers. Other magazines, from Ladies Home Journal to American Home, were quick to see the merits of the ranch house, and magazine competitions for ranch-house designs were rampant in the postwar years. Plans were offered for sale through special issues, catalogs, and plan books. However, it was the merchant builders—the producers of town-sized suburbs—who spread the ranch house across postwar America.

Not surprisingly, as ranch-house design moved out of the realm of the architectural ideal into the reality of speculative construction, architects and builders took many liberties with the original idea. Some observers particularly decried the popularity of such spread-out houses in regions where keeping warm in winter was more critical than the ranch’s indoor-outdoor living opportunities.

In response to these criticisms, the house changed somewhat as it moved eastward and northward, and regional variations became common. In the cooler, damper climates of the Northeast, for instance, the ranch house profile tightened into what is now sometimes called a “massed ranch.”

Building materials also changed over time and distance. A major feature of prototypical ranch house design was a mixture of building materials. Stone, stucco, vertical board-and-battens, clapboard siding, and brick were all popular, and as many as three of them might meet on a single façade. In the East, brick was a frequent choice for exterior walls.

Although the 1950s ranch house was typically small, the open floor plan, with its combined living and dining spaces and its large glass wall areas, went far to make up for its diminutive size. Glass patio doors put the spotlight on the rear of the house, where most family activities—backyard barbecues, children’s games, grownups’ cocktail parties—took place. The front door, in fact, was often consciously de-emphasized in the asymmetrical ranch façade, so cleverly hidden in a side-facing projection that it was barely discernible from the street.

Gable roofs were most common—side gables on the long main block, front-facing ones on wings—but there were also a good many hip roofs. All had sheltering, overhanging eaves. Massive chimneys of stone or brick on the front walls also were enticing to families in search of warm, inviting spaces.

Windows were large in the public areas of the house but generally smaller and set high on the walls in the bedrooms. Steel casements, popular before the war, gradually gave way in the ’50s to aluminum windows of various sorts—sliders, double-hung, awning, or jalousie. The living room’s picture window often consisted of a large center pane flanked by two sets of operable casement or awning windows.

Now this seemingly simple house is getting the kind of scrutiny from architectural historians that will likely yield the answers to a range of questions: How many different types of ranch houses are there? Is there a difference between a ranch house and a rambler? What’s the cutoff between a high-style ranch and a mid-style modern? Stay tuned—the architectural world’s investigation has just begun.