The front hall boasts a 1750 chest made in Ipswich, Massachusetts, which has its original finish and brasses. An 18th-century Dutch lantern hangs above.

Photographs by Sandy Agrafiotis

Homeowner Tom Johnson saw this house for the first time in 1974, when he happened to be dating the owners’ daughter. “I walked in and said, ‘I want your house,’” he recalls. “It was love at first sight.”

The house he fell for was built in 1972 by a pair of passionate historic preservationists who set out to reproduce the John Sedgley House of York, Maine.

Above the fireplace in the library hangs a 1690 overmantel painting from Maryland, featuring marbleized mouldings and turnings. Below it is a fragment of a 19th-century banner weather- vane. The sconces are Dutch, and the wing chair upholstered in needlepoint dates to 18th-century England. The smaller chair, with flame-stitch upholstery, was made in Boston in 1700.

Probably dating to 1715, the Sedgley homestead is thought to be the oldest house in Maine still on its original site. “They collected hardware, old timbers, paneling, and other old-house parts for 20 years while they planned to build,” Johnson says of the replica builders.

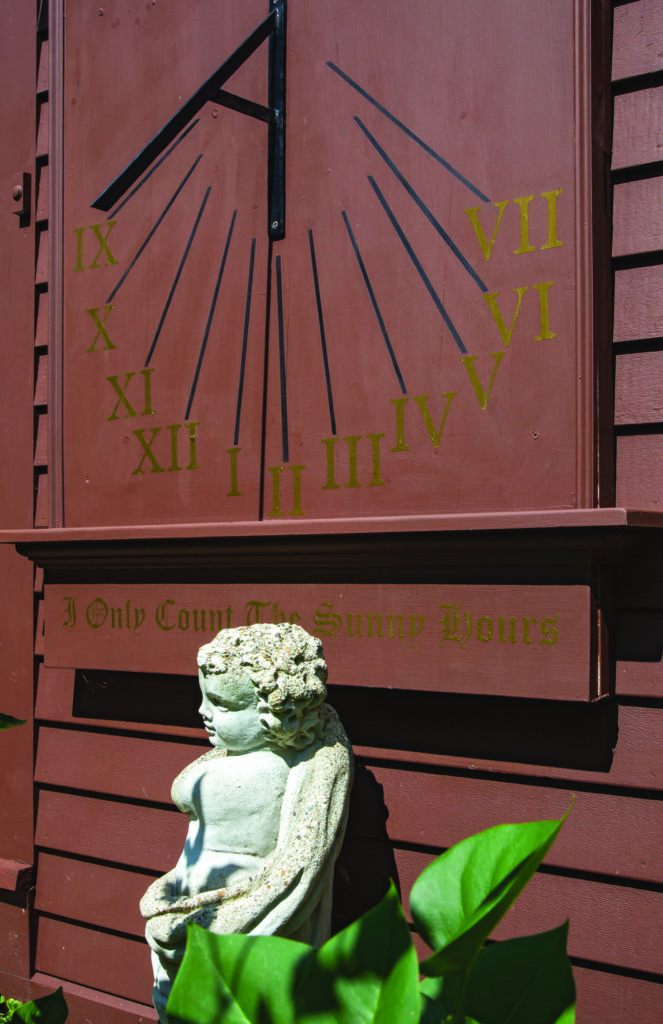

The result was an utterly convincing two-and-a-half-storey, 2,000-square-foot saltbox Cape built on a rise in Cumberland, a coastal Maine town just north of Portland. With its nail-studded front door, massive central chimney, six-over-six windows, and cedar roof, it can easily be mistaken for an 18th-century survivor.

An English Queen Anne table ca. 1760 is surrounded by reproduction chairs made by Wallace Nutting. Under the large painting stands a spice chest made in 1680s London, inlaid with bone and ivory, a miniature version of the massive kas (cabinet) across the room.

After his encounter with the house, Johnson launched a preservation career with a job as a White House curator. He has headed up museum organizations including the Old York Historic Society. Today he’s executive director of Portland’s Morse–Libby House. More commonly known as Victoria Mansion, it is a grand 1860 brownstone Italian Villa with the country’s only extant interior designed and furnished by Gustave Herter.

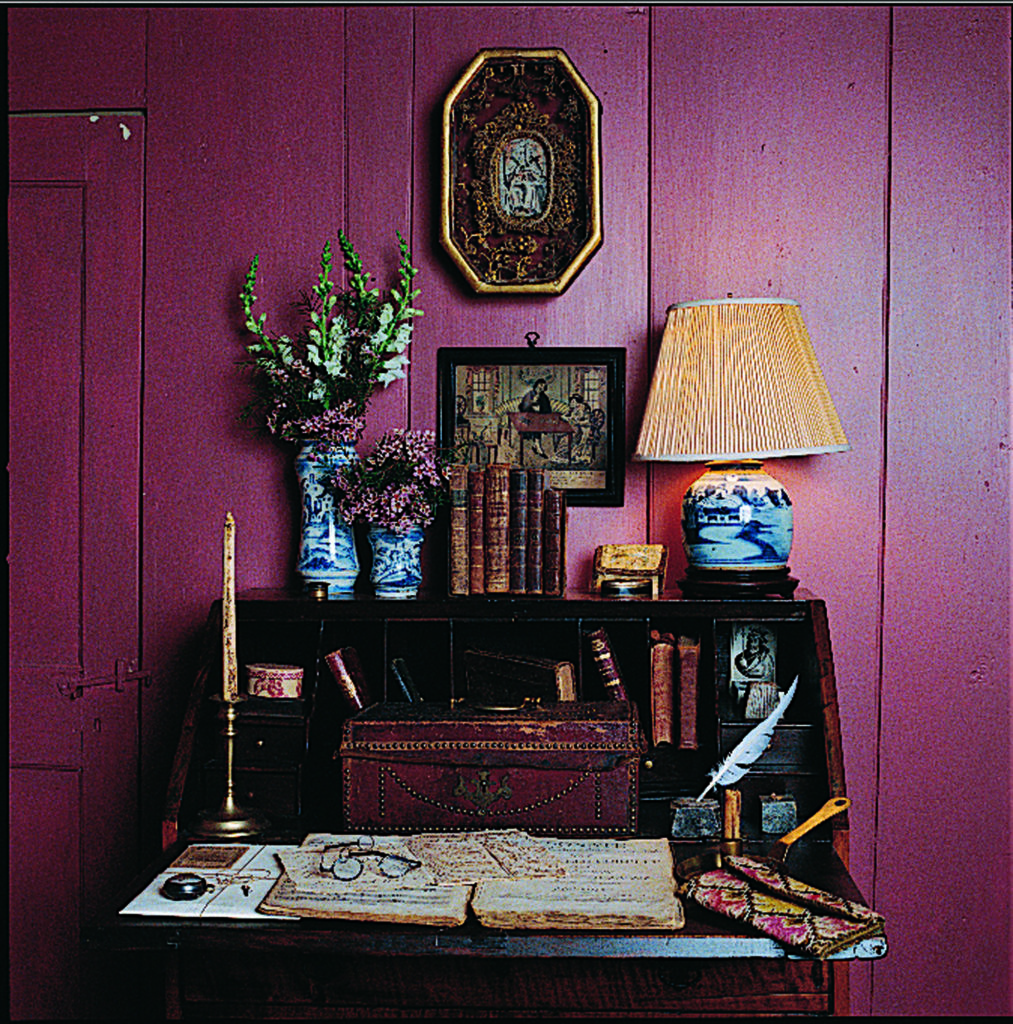

When the replica house he had fallen in love with years earlier was offered for sale in 2014, Tom Johnson bought it. He has been filling its rooms with a superb collection of antique and reproduction furniture, lighting fixtures, art, and books. “A lot of the furniture came to me after my parents passed away,” he says. “They were knowledgeable collectors and amassed some very nice pieces that happen to look great in this house.”

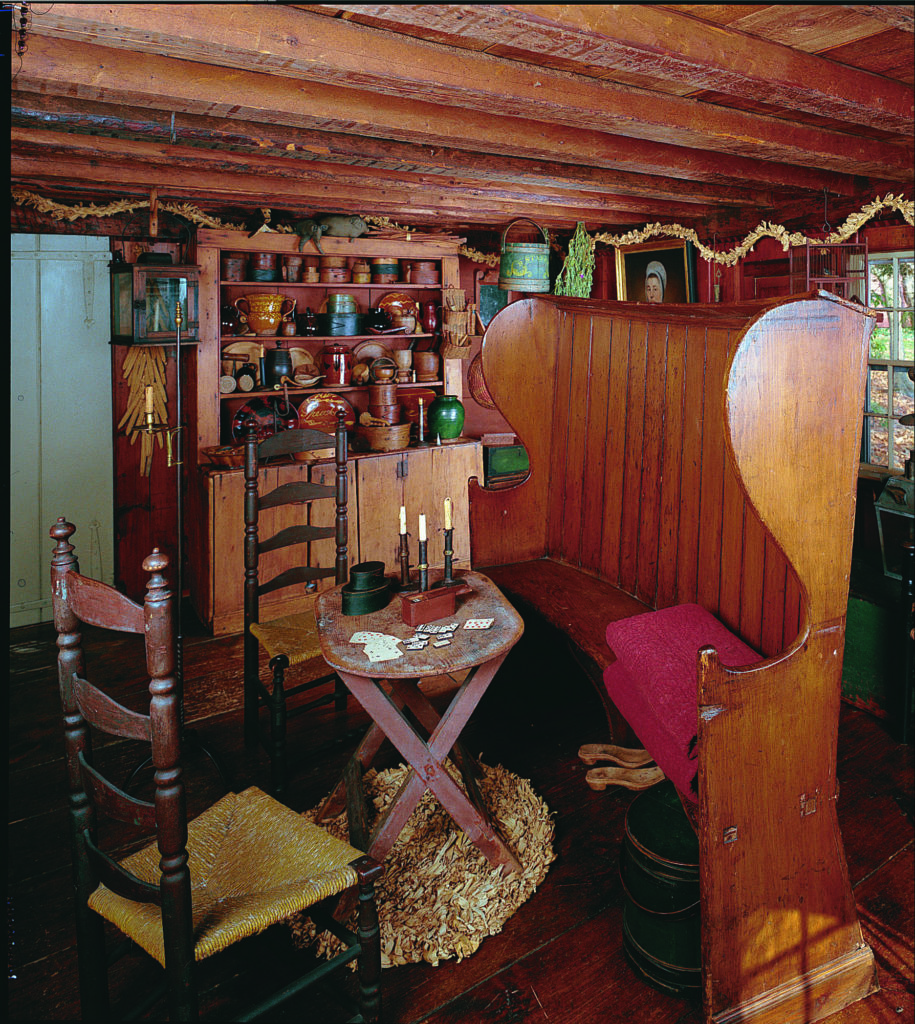

While the house’s façade gives the impression of a faithful reproduction, the building is actually balloon framed, with 18th-century timbers attached to the structure. Another giveaway is the large window on the rear wall. In the apparently historic room, which faces south, that window introduces ample natural light while providing views of the garden behind the house. The kitchen, unapologetically functional, nods to the past with a cage bar.

An English Arts & Crafts court cupboard occupies a kitchen wall. On top are an 1810 French pewter tureen and an early 18th-century American spice chest on ball feet.

“People just loved these in the 1970s,” Johnson says. “They were all inspired by the original at the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, Massachusetts.”

The front door, studded with nails in a diamond pattern to reproduce a 17th-century door, was installed by the original owners/builders. It leads into a central stair hall decorated with Moses Eaton reproduction stencils applied by the first lady of the house. Johnson, too, added painted decoration when he treated the dining-room fireplace surround to a faux marble finish.

Tom Johnson did not create a pure period interior. Furnishings include German 17th-century chests, Williamsburg reproduction wing chairs, Colonial Revivalist Wallace Nutting chairs, an English Arts & Crafts court cupboard, a rare 1750 chest with its original finish and brasses made in Ipswich, Massachusetts, along with unassuming contemporary pieces. Johnson is fond of 18th-century Dutch brass lighting fixtures and has collected several, including a six-arm chandelier that has been electrified. It hangs over the seating area by the large window in the keeping room.

While Johnson does not insist on furnishings from any particular era or place, his curatorial instincts lead him to correctly identify each piece. He’s had surprises, as when he sought to authenticate a Madonna painting that hangs in a corner of the dining room. “It was sold as an original 17th-century painting,” he says. “But it’s one of the great World War II-era fakes. I had the paint pigments tested. They date to the 20th century.”

The dining room chandelier, too, is suspect in his eyes. “I don’t believe that it is 18th century, though it is made to look like it. A careful examination of the way the metal is formed makes me think it’s an Arts & Crafts-era piece.”

He likes to collect interesting art. A recent find is a large 1758 painting of a French chateau found at an estate sale in Greenwich, Connecticut. “Because of its size and shape, I think it was originally an overmantel painting,” Johnson says. “It turns out, all sorts of naughty things are going on: men are relieving themselves under the trees, a man is reaching into a woman’s bodice, but you never see any of it unless you look closely.”

After three years of living here, he still marvels at the joys of a late 20th- century house. “I had always lived in old houses,” he says, “and this is so different. The house may look old, but it’s plumbed, wired, and insulated like a new house. Nice and warm in the winter.”

The house was built by a couple of ardent preservationists, who used the 1715 Sedgley House in York, Maine, as their model.

John Sedgley, the model for a replica.

This center-chimney Colonial house—two rooms down and two rooms up off a tiny hall, with a saltbox rear elevation—was built by Englishman Jonathan Sedgley in 1715, and is probably the oldest house in Maine still on its original site. It is also well preserved; recent owners have included a pair of antiques dealers specializing in 18th-century country furniture.

The Sedgley Homestead in York is privately owned and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Besides the original house, it includes a ca. 1720 farmhouse, a 19th-century carriage house later converted to a dwelling, a few outbuildings, and a Sedgley family cemetery. Several 200-year-old fruit trees have survived.