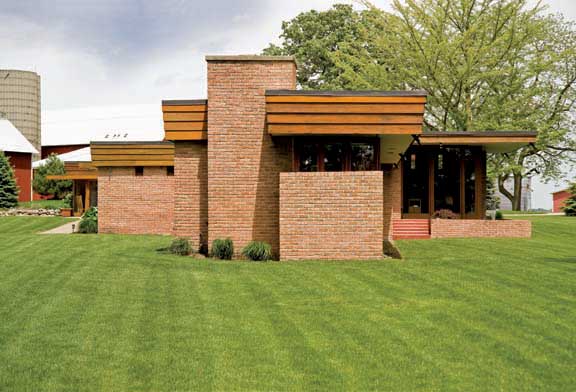

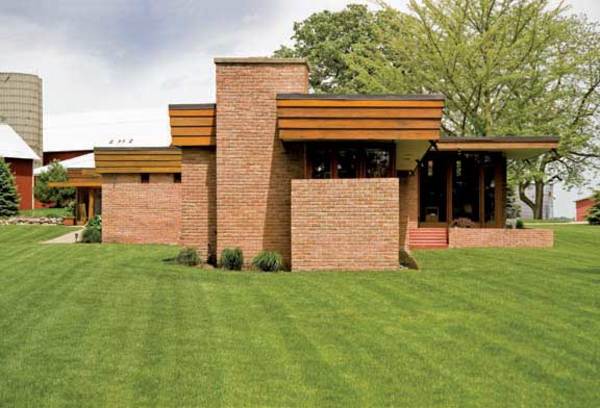

The 1950s cypress-and-brick farmhouse, meticulously restored by Mike and Sarah Petersdorf, has received several preservation accolades.

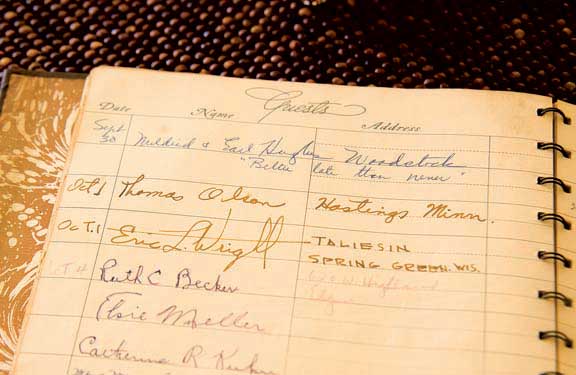

In 1948, Robert Muirhead, an Illinois farmer, packed his wife, Elizabeth, and their five kids into the car and headed off for Wisconsin, hoping to get a look at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin. A mechanical engineer by training—and an avid reader of Architectural Forum—Muirhead was in the market for an architect to replace the two-story clapboard house that had stood on the family farm for years. He didn’t expect to encounter Wright, but the architect’s longtime secretary, Eugene Masselink, saw the Muirheads studying the property and invited them in to meet the master. A stream of correspondence followed, and in 1951 construction began on the Muirheads’ new home, a five-bedroom Usonian, Wright’s Prairie house for the everyman.

Muirhead lived in the home until 1984, then sold it to his grandson Charles, who resided there with his family until his death in 2001. By then, the property had begun to show its age. Water damage, crumbling masonry, an ill-advised exterior paint job, and a patio enclosed to house a hot tub had all marred the home’s unique mid-century appeal.

In 2003, Charles’ sister Sarah and her husband, Mike Petersdorf, relocated from Minnesota to restore the house. The project, funded in part by the sale of family farmland to the county forest preserve system, was completed in December 2005. “Returning and renovating the house was actually an easy decision for us,” says Sarah. “It was simply what needed to be done to preserve the house and the family’s association with it. Some may laugh at this, but the house is like family. It represents my grandparents in every way, from their style of living to their love of nature and farming.”

Arguably the only Wright-designed farmhouse ever built, the house was specifically tailored by the architect and homeowners to the family’s working lifestyle. Robert wanted a workshop where he could service farm machinery, and Elizabeth needed a dining room that could accommodate not only the family, but farmhands, too. And since she was feeding a crowd—with only occasional trips to town for provisions—Elizabeth demanded lots of storage space in her kitchen. What’s more, the Muirheads wanted a clear separation between these functional areas of the house and the private living quarters, a slight deviation from the free-flowing spaces typically characteristic of the Usonian style. Wright’s initial hand drawings proposed two buildings separated by a 100′ covered open-air walkway. When Elizabeth explained the impracticality of such a scheme to Wright, he huffily ripped the drawing in two, overlapped the two halves to shorten the span, and agreed to enclose it.

Robert Muirhead acted as his own general contractor and did much of the work himself, wiring the house, pouring concrete floors, building cabinetry, and installing most of the windows. “When Wright’s first blueprints came, they were sent out to an engineering firm in Wisconsin for assessment and came back at $70,000,” says Mike. “Sarah’s grandfather gave the go-ahead to begin the construction, but I think his thought all along was, ‘I’m going to do a lot of this myself.’” (Wright’s building estimate was $24,000, plus a 5-percent fee; extant receipts suggest the final cost was between $50,000 and $55,000, with Wright’s fee at 9 percent, although there’s some doubt he ever collected that much.)

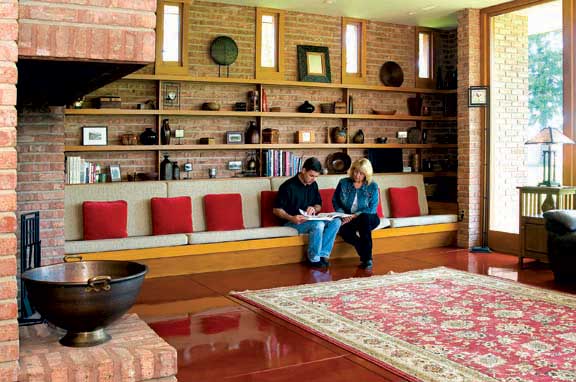

The massive brick hearth and built-in shelves are classic Wright touches in the open, sunny living room.

Restoration the Wright Way

For their restoration, Sarah and Mike followed her grandfather’s lead, taking on much of the work themselves, referencing original drawings and blueprints, letters, and family memories of the house. Not surprisingly, the first job they tackled was the flat roof, which had begun leaking within a few years of the home’s completion. “Most of the damage to the house was due to the leaky roof,” notes Mike. “Patches of tar had been placed here and there, but those never really kept all the water out. We had to completely tear out the old roof and had a roofing company put tapered insulation under the roof deck and expand the size of the drain pans.” Now, he says, leaks aren’t a problem—nor is the winter’s considerable snow load.

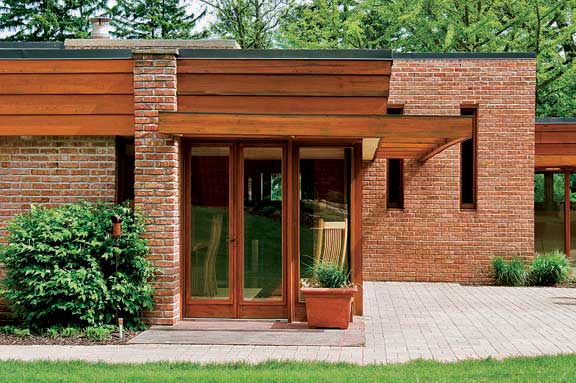

The other major exterior project was rejuvenating the brick and cypress façade. The wood was stripped of paint and resealed; compromised boards were replaced. Although the pale pink Chicago common brick used in the construction was no longer available, Sarah’s father directed Mike to a pile that he’d buried on the property decades earlier. (Instructed by Sarah’s grandfather to clean up around the property, he’d decided that burying the extra brick was easier than stacking it neatly.)

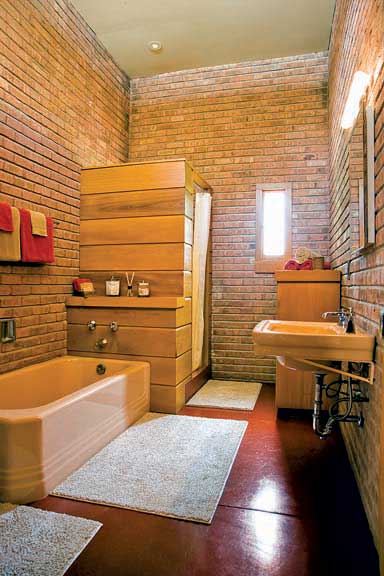

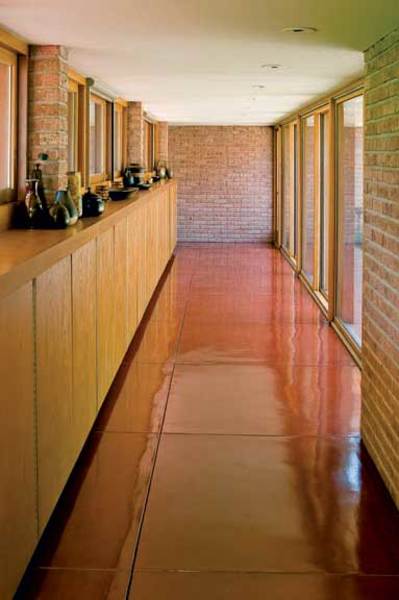

The home’s distinctive red floors were replicated using a topcoat nearly identical to the original material.

A pressure wash removed the accumulated moss and dirt, but the masons the couple engaged had trouble working with it. One of the carpenters Mike and Sarah had hired for the restoration led them to an 82-year-old man who had worked for the company that originally laid the brick. Although he hadn’t worked on the Muirhead house, he was familiar with the material. “He told us that the key to working with the bricks was to soak them overnight,” says Mike. “They’re like a sponge; when you lay mortar on them, they suck all the moisture out of the mortar and you can’t shape it. That was the problem. The other masons were trying to treat it like glazed brick.”

Inside, all the cypress plywood had to be stripped and clear-coated and the entire house rewired, a project that included updating 169 original can lights (some of which had charred the ceiling joists) inside and out. The original fixtures were galvanized boxes inserted above the ceiling and faced with open squares of plywood so they sat flush with the plywood ceiling. But when Mike and Sarah decided to insulate the ceiling, the heat-generating boxes presented a major fire hazard, so they replaced the original lights with insulated can fixtures in a similar design.

All the non-load-bearing walls were removed from the bedroom wing in order to replace the concrete flooring, which had sunk over time. “Where it meets the foundation, the floor had stayed put,” observes Mike, “but they used dirt to bring the floor up to grade, and that had settled. So we corrected it with a limestone fill.” The 4′ x 4′ floor panels had to be re-poured and colored to match the red hue of the originals, which had been created with a topcoating product called Colorundum. “That’s no longer made, so our concrete company used an almost identical product made by Butterfield Color,” explains Mike. “It’s applied the same way—you pour a concrete square, let it sit until it’s firm but still soft on the surface, then sprinkle the powder over and work it in with trowel.” It took seven test squares to get the color just right. Mike and Sarah also removed the enclosed hot tub that had been attached to the master bedroom and restored the small patio as Wright had specified.

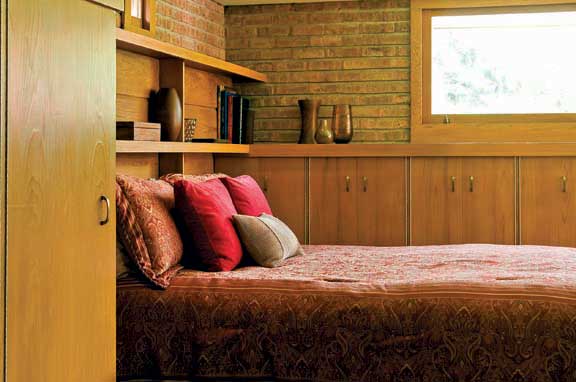

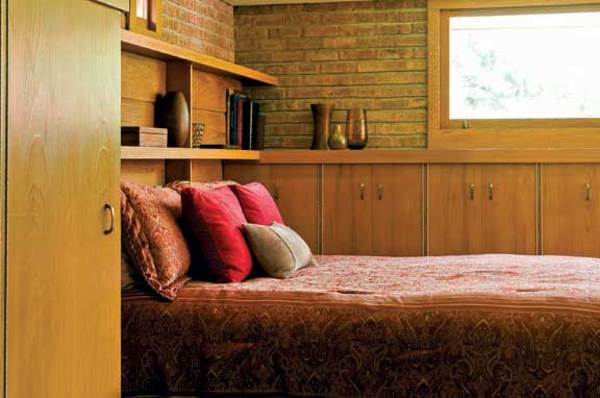

Warm cypress built-in shelves and cabinets make this bedroom a cozy and welcoming space.

Living Legend

As with many of Wright’s projects, his vision of the Muirhead farmhouse included furnishings of his own design, but few of these were ever built. Luckily, the cypress plywood for these unrealized projects was neatly stored in the farm’s workshop; using the original plans, Mike has taken a crack at realizing some of those pieces, including a pedestal bed, end tables, and hassocks for the master bedroom.

Now in excellent condition, the 3,200-square-foot residence is not only home to the Petersdorfs and their two sons, but also open to Wright fans as a bed and breakfast. Numerous visitors from around the country and abroad have made the trip to the Illinois countryside, eager to spend a night in a Wright-designed house. Looking back at their undertaking, Sarah says, “We never had a second thought about what we were doing. Neighbors often questioned our sanity, and at one point asked why we didn’t just knock the place down and build something nice and new. We just smiled at the suggestion, recognizing that they simply lacked an understanding of the significance of the structure.”

Online Exclusive: Check out our directory of Wright houses to rent for a night’s stay.

Frank Lloyd Wright Reading Recommendations

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE ROOMS Interiors and Decorative Arts by Margo Stipe (Rizzoli 2014) Intimate immersion inside the Prairie houses, Fallingwater, Hollyhock House & more.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PRAIRIE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2006) Interiors and details of over 70 extant buildings of the Prairie School years. How Wright broke from Beaux Arts symmetry to create “a tartan plaid of main spaces and secondary spaces, of public rooms and circulation spaces”—with brilliant results.

THE PRAIRIE SCHOOL: Frank Lloyd Wright and his Midwest Contemporaries by H. Allen Brooks (Norton 2006) From its beginning to its end, Prairie School beyond Wright. Discusses the architects’ various contributions.

HOMETOWN ARCHITECT: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois by Patrick F. Cannon (Pomegranate 2006) Houses 1887–1913; this book is the pilgrimage documenting 27 Wright houses in Oak Park and River Forest. Photos include interiors.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2005) From the 1908 Prairie School Robie house in Chicago through his textile-block houses in Los Angeles, and on to Fallingwater and Taliesin West, here are FLW’s residential commissions all in one huge volume.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S INTERIORS by Thomas A. Heinz (Gramercy Books 2002) Shown are 1,000 interiors, including houses and public and corporate buildings, from throughout Wright’s career. Horizontal lines, natural elements, concrete, and brilliant use of three dimensions.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S GLASS DESIGNS by Carla Lind (Pomegranate 1995) Innovative design for windows, skylights, and decoration.