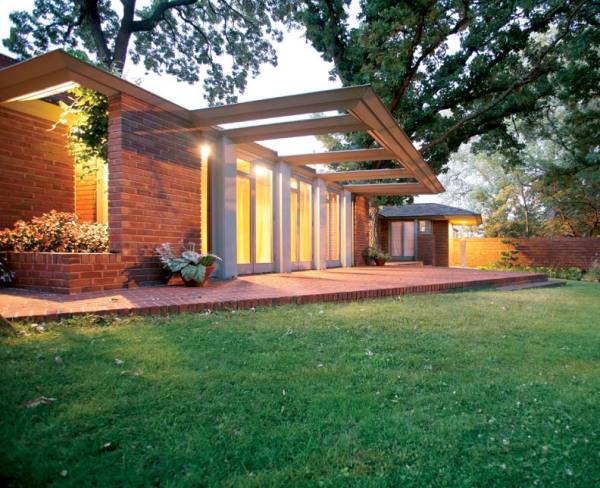

A prominent feature of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Willey house, designed for a Minnesota professor and his wife, is an expansive cantilevered trellis, which appears to hover over a row of French doors.

Steve Sikora

After moving to Minneapolis in 1932, Nancy Willey wrote to Frank Lloyd Wright, asking him to recommend a like-minded architect to design her house. Nancy and her husband, Malcolm, a University of Minnesota sociology professor, had purchased a lot with a view of the Mississippi River and had a budget of about $8,000. She never dreamed that Wright himself would take on such a small project, but—idled by the Great Depression—he did, writing back, “Nothing is trivial because it is not big.”

Nearly 75 years after its completion, the Willey house has undergone a complete restoration. And despite the building’s modest size, the restoration efforts surrounding it have been gargantuan—and full of inventive techniques.

An Architectural Bridge

Most building historians view the Willey house as the bridge between Wright’s Prairie designs for wealthy clients and his Usonian homes for the middle class. In addition, a few historians speculate that the Willey house is a prototype for the rambler. The house, completed in 1934, is elongated, compact, and single-level, a concept that amazed people at the time. A columnist for the Minneapolis Star wrote that the Willeys were building “an upside-down house” with bedrooms in the basement.

From the street, the Willey house has a modest appearance, but its wide, low-slung eaves betray its Wrightian roots.

Steve Sikora

Like many of Wright’s experimental designs, the house had some structural problems from the very beginning. In 1941, Nancy complained to the architect that moisture was entering the house through gaps caused by seasonal expansion between the roof and chimney. Wright responded with these instructions: “The tops of the chimney and walls should be coated twice with rubberoid mastic. This will solve your problem.” It didn’t.

Over the years, the structural issues, along with other factors, began to reduce the house’s livability. One of these issues was its fame. It was (and still is) sought out by uninvited architecture buffs, who often trespass on the property just to push their noses against the windows. Additionally, in the 1960s, the Minnesota Highway Department placed Interstate 94 a mere 100 feet away from the front of the house, filling open windows with the din of traffic noise. By the time Steve Sikora and his wife, Lynette Erickson-Sikora, bought the house in 2002, it had been mostly unoccupied for seven years, and was in poor condition. Water entered in many places; mice had invaded the roof; and numerous bricks were broken, spalled, or efflorescing. Working with contractor and master carpenter Stafford Norris III and his brother Joshua, the new owners embarked on a total restoration.

A Cantilevered Conundrum

One of the home’s most prominent features is a 9′ x 15′ horizontal trellis with three integrated skylights, which is cantilevered over the front of the house and covers a wall of French doors. Wright envisioned wisteria vines, planted in boxes flanking the doors, growing over the trellis to softly frame the living room view.

Before the restoration, an aerial view shows how damaged the trellis had become. The three integrated skylights can be seen clearly in the middle of the frame.

Steve Sikora

The initial inspection by the Sikoras’ contractor showed that all of the materials in the area of the trellis were greatly deteriorated, including the wood trellis itself and its sheet-metal cap, the skylight panes and their steel frames, rock-wool roof insulation, and various layers of roofing. For decades, the water that Nancy Willey had complained about had been trickling through the roof toward the trellis, rusting its cap and the skylight frames. Apparently, Wright had foreseen the potential for water problems at this spot. He had sent the Willeys a drawing of a built-in gutter system, but it arrived after the trellis had already been constructed, and the Willeys couldn’t afford to rebuild it.

Rotted mullions between the French doors show the aftermath of decades of water damage.

Steve Sikora

Willey House Trickle-down Effect

Damage was also evident in the wall of French doors directly beneath the trellis. Since Wright liked to break down barriers between the indoors and out, he had designed the brickwork in a continuous pattern from the front terrace through the living room floor. To accentuate this detail, he specified that the French doors have no thresholds. When Nancy Willey complained that this would invite water, ice, and vermin into the house, Wright’s only concession was to suggest strips of leather for the bottoms of the screen doors. Nancy Willey disregarded Wright, and had aluminum thresholds installed beneath the doors. By 2002, the mullions between the French doors had rotted. As a result, the trellis and the living room roof were being supported largely by the door jambs, and the cantilevered trellis was drooping.

To repair the damage, the Norris brothers began by removing the skylights and the metal cap, tarpaper, and upper sheathing from the trellis. Next, they took off the roofing materials, revealing “sisters” that previous restorers had nailed to the rafters to strengthen the roof. The contractors also discovered that the rafters were inserted into pockets in the brick wall at the rear of the house for support, a feature that was incompatible with today’s building code.

Trellis Tonic

Custom-made steel stiffeners shaped like a W help strenghten the trellis support beams. They were later covered with plywood and ice-and-water shield, and capped in copper.

Steve Sikora

The spine of each of the trellis’s cantilevered beams is, per the original construction, a pair of 2x6s lying on edge. These 2x6s were chamfered at the top and bottom to mate with the upper and lower sheathing boards, and each beam ties to the end of a roof rafter, with the house’s front wall functioning as a fulcrum. These original elements were found to be in salvageable condition. A structural engineer hired to consult on the trellis designed steel stiffeners with a “W” cross-section to help straighten and lift the trellis; these stiffeners were screwed to the paired 2x6s that form the trellis’s spine.

Like almost all other visible wood in the house, the trellis bottom was originally sheathed with cypress, which was in good enough condition to be retained. Stafford Norris reconstructed the upper sheathing of the trellis in plywood, covering it with ice-and-water shield, and—70-plus years after the fact—installed Wright’s gutter system. A local roofing contractor then replaced the trellis’s original steel cap with copper.

Replacing the skylights became a trial-and-error process, because, Norris says, “The skylight openings aren’t square.” Three sets of copper frames were fabricated before a snug fit was achieved. Norris also discovered that the frames’ original geometry and bearing tilted them toward the house instead of away from it, adding to problems with water infiltration. So the new frames were designed with a half-inch pitch away from the house.

Norris applies a gray stain to the wooden underside of the trellis. The color was specified by Frank Lloyd Wright for the original design.

Steve Sikora

Restoring the skylight panes proved problematic, too, because they also were all slightly different dimensions. The first set of panes didn’t match the template and cracked upon installation. A second set fared better, but still needed to be sealed with creative weatherstripping and caulking.

While the roof was open, Norris took the opportunity to install air-conditioning ducts and wiring in the deep soffit that runs across the front of the house. Most of the original rafter tails had rotted and were removed. Norris removed the old sisters and replaced them with new ones, attaching them with screws and glue. String lines running across the rafters assured a flat, straight roof. At the back of the roof, the out-of-code niches used to hang the rafters were filled with bricks and mortar. Norris installed double-thickness ledgers and special-order hangers to accommodate the roof pitch, which slopes 4 1/2″ per foot.

Of the double ledger, Norris explains, “You can’t place hangers against pressure-treated wood because the hangers will corrode. But wood next to brick must be pressure-treated because bricks transmit moisture.” Therefore, each ledger is composed of a treated rear board and an untreated front board. With the roof structure repaired, the inter-rafter spaces were filled with Icynene foam-in-place insulation, the roof was sheathed, and new cedar shake shingles were installed.

Threshold Therapy

Norris works to install the new threshold, which protrudes 7/8″ above the old floor to help keep water out.

Steve Sikora

Creating workable, effective thresholds for the French doors was another challenge. Owner Steve Sikora came up with the idea of a brick threshold—a row of bricks with a slight ridge. Based on Sikora’s design, Norris created wood prototypes and had rubber molds made, which were used to create the threshold bricks. After removing the French doors and bracing the roof, Norris used a circular saw with a diamond blade to cut a straight-edged channel in the brick floor. Then he laid mortar in the channel and bedded the threshold bricks, which protrude 7/8″ above the rest of the floor. When that mortar had set, he rebuilt the terrace.

Before placing the threshold bricks, Norris had built new mullions for the French doors. Each mullion stands on a steel plinth block; bolts run through the base of each block and are embedded in concrete footings. The mullions are not pressure-treated lumber because pressure-treated wood tends to twist and warp; instead, they’re made from clear pine. New French doors, jambs, and exterior trim matching the originals were created by a local cabinetmaker from meticulously sourced old-growth cypress. Norris used a gray stain on the exterior cypress, as specified by Frank Lloyd Wright, and in the end, he says, “The doors blend in pretty well with the old wood. We got lucky.”

Today the house that Wright created is better than new—and likely beyond Nancy Willey’s wildest dreams.

Frank Lloyd Wright Reading Recommendations

As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE ROOMS Interiors and Decorative Arts by Margo Stipe (Rizzoli 2014) Intimate immersion inside the Prairie houses, Fallingwater, Hollyhock House & more.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT PRAIRIE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2006) Interiors and details of over 70 extant buildings of the Prairie School years. How Wright broke from Beaux Arts symmetry to create “a tartan plaid of main spaces and secondary spaces, of public rooms and circulation spaces”—with brilliant results.

THE PRAIRIE SCHOOL: Frank Lloyd Wright and his Midwest Contemporaries by H. Allen Brooks (Norton 2006) From its beginning to its end, Prairie School beyond Wright. Discusses the architects’ various contributions.

HOMETOWN ARCHITECT: The Complete Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright in Oak Park and River Forest, Illinois by Patrick F. Cannon (Pomegranate 2006) Houses 1887–1913; this book is the pilgrimage documenting 27 Wright houses in Oak Park and River Forest. Photos include interiors.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: THE HOUSES by Alan Weintraub (Rizzoli 2005) From the 1908 Prairie School Robie house in Chicago through his textile-block houses in Los Angeles, and on to Fallingwater and Taliesin West, here are FLW’s residential commissions all in one huge volume.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S INTERIORS by Thomas A. Heinz (Gramercy Books 2002) Shown are 1,000 interiors, including houses and public and corporate buildings, from throughout Wright’s career. Horizontal lines, natural elements, concrete, and brilliant use of three dimensions.

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT’S GLASS DESIGNS by Carla Lind (Pomegranate 1995) Innovative design for windows, skylights, and decoration.