The English-style stone house is a work of art and craftsmanship.

Doug Mancuso took the call on a chilly fall day. A homeowner wondered if the designer would take a look at the property he had just purchased, an old stone house that needed restoration work. The owner’s story of the 1700s English-style farmhouse intrigued Mancuso, a partner of the firm Period Architecture Ltd, located in West Chester, Pennsylvania; Mancuso set out to see it, navigating a dirt road, thicket of woods, and a small bridge as he snaked his way through the rolling countryside west of Philadelphia.

When Mancuso saw the house, he was stunned. Despite its genteel name, Cold Springs Farm was a crumbling mess, neglected for decades and subjected to an inappropriate addition and mortar-washed stucco façade that hid the original stonework.

Authentic interiors include exposed stone walls in the second-floor hall.

“You have to imagine what the property and existing house looked like when I first arrived,” Mancuso says. “Overgrown, uninviting, neglected, some deferred maintenance, and a terrible 1970s addition out back.” The architect’s doubts increased when the owner explained the scope of the project: a two-bay extension of the original three-bay colonial farmhouse to form a horseshoe shape, set off with a formal courtyard garden, all in proper historic style. The homeowner, a European master craftsman with Old World values, wanted to participate in the renovation.

“I think I was more skeptical than anything,” Mancuso says. “I knew what he was describing and what it would take to get there, but I wasn’t convinced he knew what he was getting into. Well, obviously, I was dead wrong.”

To say that Cold Springs Farm was saved is an understatement. Today the property, a massive stonework home set on five acres of pastoral countryside, is a perfect mingling of pristine craftsmanship and contemporary comfort. Guided by the vision of the homeowner—an extraordinarily detailed, expert stonemason who grew up amid ancient architecture in his native Hungary—Mancuso and his partners devised a plan to restore the stone house to its original beauty, while adding modern features such as a state-of-the-art kitchen and more space, ultimately more than doubling the original home’s size.

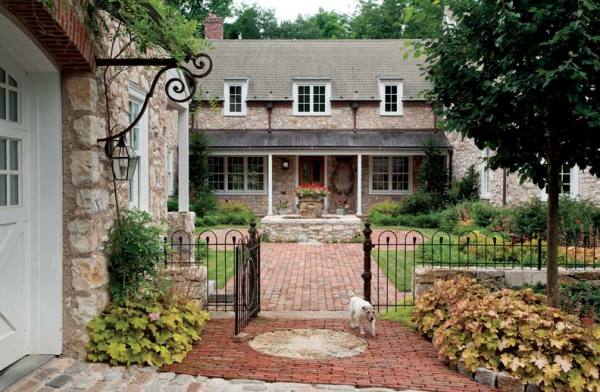

Visitors are greeted by a formal courtyard garden paved with antique brick.

First, Mancuso embarked on a serious study of the property’s historic precedence, a job that he and his partners make more play than work. “We were excited from the very first moment of the design,” Mancuso says. “We realized the incredible opportunity to expand on a story started over 200 years ago.”

The home’s location, built into a hillside and perched on a rise, places the front property squarely in the spotlight. And there is much to see here, including a pavilion with a cedar shake roof, a stone fountain, and a cupola of hand-carved limestone and European clay tiles that serves as a chimney for the fireplace. Spread out in view just beyond are the stable yard, pond, and a log cabin, the owner’s personal getaway.

The dining room features original exposed beams.

The exterior of the home itself, girded by 20″-thick walls, is a sublime presentation of old European formality. The original 1700s farmhouse consisted of three bays. To meet the owner’s wish for more space, the existing structure was restored and extended to accommodate a large addition. Today the space is demarcated by function. To the left of the entryway are the kitchen and other family spaces; to the right are the more formal rooms, a European gesture that suits the homeowner’s lifestyle. Upstairs, a master bedroom suite occupies one side, with three additional bedrooms on the other.

The materials are of almost unimaginable heft: tons of stone harvested from the site, slate, brick, copper, steel, and granite—all a great boon to longevity and upkeep. “The owner is keen on low maintenance,” Mancuso says. The owner also has a deep commitment to the property, putting in countless hours of masonry work to see that the house lasts for at least another 200 years. “He had a very clear vision,” Mancuso says. “Things might have been cut short if he hadn’t had his [master craftsman] ability.”

The master bedroom has an Old World stair design that leads to a home office.

Also key to the project was the owner’s right-hand man, Bret Wade, a master carpenter who has begun learning masonry. “We had to execute an overall vision, all of our collective visions,” Mancuso says. “Everybody was on board.”

A closer look at the exterior details reveals grandeur multiplied: tiny Gothic arch windows, shed dormers, and a graduated slate roof with an exposure that decreases as it nears the top, Mancuso’s way of making it appear even grander.

The home’s entryway is a gentle introduction to the European influence—and hand-in-hand craftsmanship—that is inherent in the house. Everywhere are artful touches: a life-size bear outside the front door (a mascot of the owner’s hometown in Hungary) that was hand-carved by a friend, the hand-stippled mahogany front door with hinges forged by a local blacksmith, and a labor-intensive staircase with square spindles of wrought iron. As Mancuso says, “It goes back to the challenges that the craftsmen faced every day.”

Entering the house, white and neutral shades dominate, allowing the eye to rest on exquisite details, such as the column plinths of limestone blocks, hand-carved by the owner. “Traditionally you wouldn’t see a stone base there; there would have been wood trim,” Mancuso remarks. The aura of permanence increases with features such as wide-plank reclaimed floors, underlaid with steel and concrete subflooring; stone thresholds; antique brick pavers; brick cornices; and salvaged timber beams. Straight ahead from the entry is the airy dining room, a reflection of the color scheme’s beautiful neutrality, with its shining reclaimed white oak floor and black walnut hutch, which the owner had made for the room.

A felled tree on the property was carved into a life-sized bear, which greets guests at the door.

Left of the entryway, through the view of an elliptical arch of radial stone, is the kitchen, probably the most meticulous blending of old and new in the entire structure. State-of-the-art appliances, including a stone pizza oven, blend with a period-inspired walk-in fireplace with crane and caldron.

In all of Cold Springs Farm, perhaps the most striking feature is what is not seen—any line that distinguishes old and new construction, all the more remarkable since most of the structure today is new. As in any relationship—and there are many that helped bring this property back to life, primarily a relationship with the past—sensitivity was foremost. “The new work had to blend seamlessly with the old part of the house,” Mancuso says. “We had to make sure massings and scale worked, that everything was appropriate and believable. There was no detail left unresolved.”