Bernhard & Priestley Architecture of Rockport, Maine, produces architecture that fits into its physical and social context.

We tend to think of historical styles in architecture as being the result of designing according to a fixed set of rules. But the definition of any recognized style is as much the work of historians as it is the work of original architects and builders. That isn’t to say that architects do not work within a defined idiom; even a cursory comparison of Georgian, Federal, Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, or Shingle-style homes provides clear evidence that their architects adhered to a distinct stylistic sensibility, if not quite a rigid set of rules.

Architectural historians, by inclination and training, like to classify things. In some cases, they are aided by the literature of philosophical movements such as the Arts & Crafts movement of the late nineteenth century or the Modern movement of the early twentieth century. More often, however, they define architectural styles retrospectively. They look back at periods when certain stylistic fashions or philosophical ideas predominated, identify common stylistic traits, relate them to concurrent social, political, or technological trends, and then give the style a name, if one has not already emerged through common use. Once a sufficient number of styles are defined with clarity, a big part of the discipline of architectural history consists of classifying buildings as being of one style or another.

The original architects and builders might easily recognize the style names applied to their work, but they might find the prescribed definitions and details oddly confining. Each new architectural style reflects a desire to replace the stylistic convention of the day: to express an aesthetic philosophy previously unexpressed or to use form, space, and material in novel ways. Their creators perceived themselves not as adhering to a new set of rules, but rather as making a break with an existing set of rules. In each era, the new work is thought to be fresh, new, inventive, and modern. Only later do the “rules” of a style become codified.

This presents a dilemma to architects seeking to create a new old house. If they adhere too rigidly to a prescribed set of rules for a style, a house can end up having a museum- or stage-like quality. On the other hand, if they depart too much from an established idiom, the results might look jarring or even silly, because knowledgeable lovers of architecture have a strong sense of what looks “just right.” Try to imagine a Greek Revival house with a round tower on one corner, or a Shingle- style house that is perfectly symmetrical.

This is a dilemma familiar to Bernhard & Priestley Architecture of Rockport, Maine, who strive to produce architecture that fits into its physical and social context. In coastal Maine and other locations where they have worked, architectural history is a big part of that context. Like many other architects who have developed a passion for architectural history and continuously explore it in their work, they have absorbed the history, almost through osmosis, and are able to work in many stylistic idioms with confidence, creating new works that are at once inventive, fresh, and stylistically consistent.

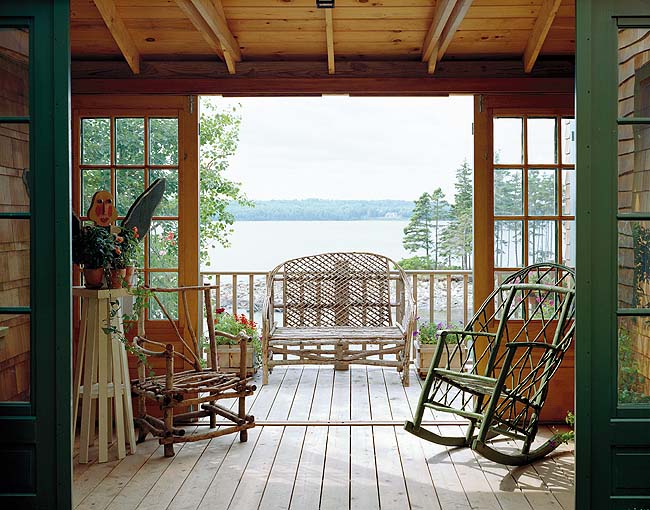

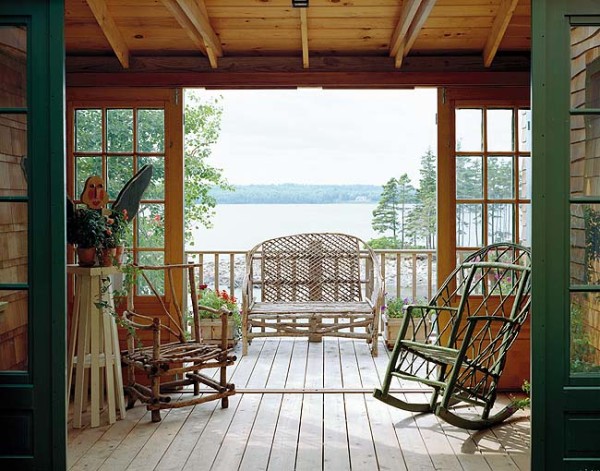

A breezeway opens onto an open porch, which offers views of the water beyond.

“We have a fairly extensive library of architects and historical styles, and we take the books out regularly, looking for precedents and inspiration,” says firm principal John Priestley, AIA. “We’ll also show them to our clients to see what kind of response they have to the images and styles. But when we work on a particular project, we don’t have a book out in front of us, or a set of rules that we follow. Typically, we apply those ‘rules’ in a more open fashion. It becomes evident very quickly when we’ve combined elements that are incompatible. That recognition comes from practice and familiarity. Most of it is in the deep recesses of your mind, so you don’t know exactly where it comes from.”

For the design of an oceanfront home in Sorrento, Maine, with a view south/southwest across Frenchman Bay toward Bar Harbor and Cadillac Mountain, Bernhard & Priestley considered context on multiple levels, from the surrounding community to the immediate natural surroundings.

“Sorrento is a rustic summer community,” notes Priestley’s partner, Richard Bernhard, AIA. “The house needed to be warm, needed to take advantage of all the views, and needed to have an informal feeling about it.” These are qualities that are a natural fit for the Shingle style, a familiar idiom for Bernhard & Priestley. “A lot of our work is Shingle style, because so many buildings on the coast of Maine are Shingle style,” says Bernhard. “Then you take a look at your local environment, and you bring that into your design. For this house, the site is over 20 acres, all wooded. We associate red cedar with wooded sites. On more open oceanfront sites, we would use white cedar.”

A fieldstone fireplace—which mimics the look of the rocky shoreline landscape—anchors the living space. A bank of casement windows opens to allow in salt air breezes. Walls are paneled in pine beadboard, while ceiling beams add interest to the space.

The house is actually a renovation of an addition onto a house originally built in the 1960s. “Today, you could not build so close to the water,” notes Bernhard. “But owners of existing homes are permitted to add up to 30 percent of the volume of an existing home, and we took full advantage of that to build a guest lodge that is connected to the main house by a breezeway.” The footprint of the main house and an existing master bedroom wing is unchanged. Much of the interior finishes of these spaces is also original.

But the exterior was bland and unappealing, with vertical siding, shallow-pitched roofs, and little architectural character. “That really became the focus of the design, to give it something that was more inspirational for its owners,” notes Bernhard. The changes are subtle but inventive. By adding deep overhanging rakes and eaves to the existing forms, the architects were able to convincingly create an entirely new and steeper “main roof pitch,” giving the original shallow-pitched roof the appearance of being a dormer in the main roof. The rest is in the details: a wide-flared shingle base over a stone water table that comes right up to the first floor window sills; rows of ribbon-course shingles with a seven-inch exposure at the first floor; a painted belt trim at the second floor level; a shallower shingle flare directly above it; single rows of shingles at the second floor level; and wide window casings all combine to convert a characterless box into a fine example of the Shingle style.

“We played a lot of games that we hope results in people guessing how long the house has been there,” said Bernhard. To the original master bedroom wing, the architects added a cupola/skylight and expansive sliding glass doors, to open the space to the view and to adjacent “outdoor rooms.”

Flagstones lead visitors through the front garden to the breezeway, which connects the master bedroom to the main house.

The design of the house proceeded simultaneously with the landscape design, the work of Karen Kettlety, Landscape Architect, now Burdick & Booher, Landscape Architecture, of Mt. Desert, Maine. “Karen liked the idea of keeping the gardens close to the house proper,” said Bobbie Burdick. “You want the attention on the house and through the house to the water. We wanted a garden that you would pass through, not just view.”

The parking area of the driveway is deliberately kept away from the house, so that owners and visitors approach on foot. The main garden, which begins at the driveway, is a hillside garden consisting of cottage-type flowers and woodland perennials, a balanced composition of flowers and lush foliage. “The overall theme is for the garden to embrace the house,” notes Burdick. “Natural materials are really crucial to a design like this. All of the stonework of the house, and the stone used for the paths, are natural materials that could be found on the site or very nearby.” The design allows the exposed stone of the rocky shore to morph into the landscape design, the stone terraces, the stone foundation walls, and on up through the fireplace chimneys in a single harmonious composition. “There is a common thread of stone from the water’s edge all the way up through the building,” says Burdick.

Beyond the master bedroom, the landscape architects created a second outdoor room consisting of an evening garden: fragrant flowers with pale or white blossoms that can be appreciated even at night. The design collaboration extended right up to the breezeway, connecting the master bedroom to the main house, for which Karen Kettlety designed a log pergola.

“We see our work as part of a continuum that’s been going on among architects for centuries,” says Bernhard. “There’s so much out there to work with. Rather than inventing something that reflects our personal taste, our style is to seek out a timeless quality that most people can respond to, even if they can’t identify exactly why.”