The gutsy centerpiece of the living room is the 10′-diameter mirror from the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach.

Dan Mayers

In New York City’s Soho, streets lined with 19th-century brick and terra-cotta buildings are fronted with smart shops and boutiques; it’s easy to believe you are in Paris or London. To find an empty lot here is unheard of. But that’s exactly what Robert and Cortney Novogratz did. They bought a condemned corner building in Soho along with the empty lot next door, which at the time was a parking lot. After restoring the three-story building to a single-family home, using architectural artifacts such as old theatre doors, salvaged hardware and old windows, they decided to take full advantage of the 21-foot by 54-foot lot next door, and drew up plans for a new town house to be built on the site. Five stories tall with 1,200 square feet per floor, the building was designed as a single residence for one family—the ultimate luxury in space-starved Manhattan.

Robert and Cortney both were determined that theirs would not be “a cookie-cutter home”; they wanted something unique. Robert had grown up with antiques, as his parents were in the antiques trade. Cortney, who’d been raised in a 200-year-old house in the South, had a keen appreciation of the past as well an innate design sense. They began buying architectural antique salvage fifteen years ago, while still in school—everything from doorknobs to oversize windows—knowing they would find a use for them someday. (Robert jokes that when the monthly rental fees on storage units became more than his mortgage payment, it was time to build.)

The island was built from the back bar and topped with a custom-made zinc counter.

Dan Mayers

They drew basic floor plans that incorporated a small elevator to take the burden off five flights of stairs. Then Robert and Cortney turned to their salvage stash for inspiration. A terra-cotta angel found in Paris was incorporated into the exterior above the front door, setting a tone of beauty and unexpected treasures. Cortney heard about a Victorian chapel (with an encaustic-tile floor) being pulled down. Though she had just given birth to her fourth child, Cortney didn’t hesitate to rush uptown to the demolition site. The floor had already been dismantled into hundreds of individual tiles, but she wasn’t intimidated: she bought the entire lot, then patiently put all of the tiles back together like a giant jigsaw puzzle for her kitchen floor.

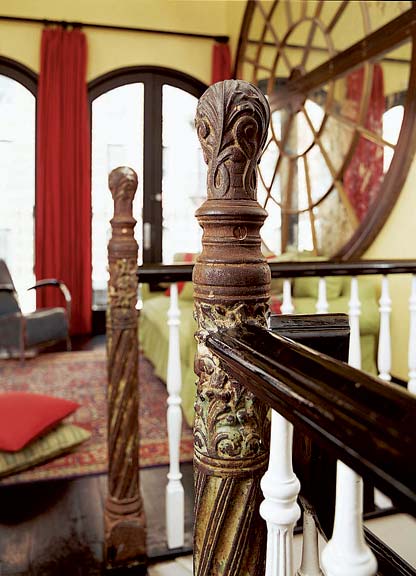

The new town house was carefully designed to look as if it were built in the late-19th century, just like its neighbors. The stuccoed and brick exterior was given “age” with salvaged limestone columns, metallic bridge lights from the 1930s, and a pair of distressed wooden doors from London. Tin ceilings were used throughout the interior, and sprinkler pipes purposefully left exposed as they are in many New York buildings of the period. Architectural elements include a cast-iron newel post, crusty with old paint and patina, accompanying wooden rails as an unexpected accent on the staircase. Metal bistro lamps from Paris, industrial factory lighting of the Forties, and a trio of Victorian wrought-iron hall lamps from Georgia are hung at different levels around the house, suggesting evolution of the rooms.

The open dining area centers on a pine farm table from Holland. Chairs are from a 1950s restaurant. The 18′ back bar provides storage. Exposed sprinkler pipes and the tin ceiling are intentional period effects.

Dan Mayers

The arresting, 10-foot-diameter, mullioned mirror is from the Breakers Hotel in Palm Beach; it became the focal point in the second-floor living room, its curves echoed by arched French windows opening onto the street. To keep the room from becoming “too serious,” Cortney placed a comfortable sofa along with a 1950s metal and leather chair from a barbershop waiting room and a pile of colorful floor pillows underneath the opulent mirror.

Another large, round, stained-glass window from a French cathedral was installed at the back of the kitchen, which was built around a kitchen island made from a 19th- century back bar. Its custom-designed zinc countertop provides striking machine-age contrast. The enormous, 18′-long back bar actually provided both the kitchen island and a storage cabinet across the dining area. Cortney added glass shelves and filled them with favorite salvage finds: colored seltzer bottles from the Thirties and Forties, and nickel-plated numerals from a diner that had been used to mark orders but are now handy at big dinner parties. The pair couldn’t resist a large hanging clock, which once kept the schedule at a European train station. It’s hard to believe the house is only two years old, filled as it is with treasures of the past.

In the master bedroom, Cortney installed an 8′-tall, leaded-glass window from in the wall across from the stairs, broadcasting the sunshine that streams in over the skylit stairwell. Her grandmother’s favorite easy chair has been updated with zebra-pattern velvet.