Of all the picturesque architectural styles popular in the first quarter of the 20th century, Spanish Colonial Revival has been the most enduring. Its varied forms include sub-styles that appear in Florida, California, and the Southwest.

Red Tile Style is another name for these houses. This 1934 hacienda in San Marino, Calif., also boasts porthole windows, arches, and a colorful Hispano–Moresque tile fountain.

Chris Considine

Preservation of Franciscan mission churches in California; designers working toward a new architecture of the American West; Hollywood romanticism; a housing boom: All of these came together to create a long-lived revival of Spanish Colonial building idioms. Most popular in what had been the Spanish Colonies, the style of white stucco and red-tile roofs also showed up in national plan books, and in the suburbs of New Jersey and Illinois.

The spanish colonial revival was in full swing at the turn of the century and continued through the 1930s. This was the most widely used of the period’s so-called Mediterranean styles—and perhaps the most historical, without that pastiche of French or Italian and Renaissance elements. In the American West, these houses were designed after the ranchos and other buildings of the Colonial period. Motifs come from the rich, long history of Spanish architecture.

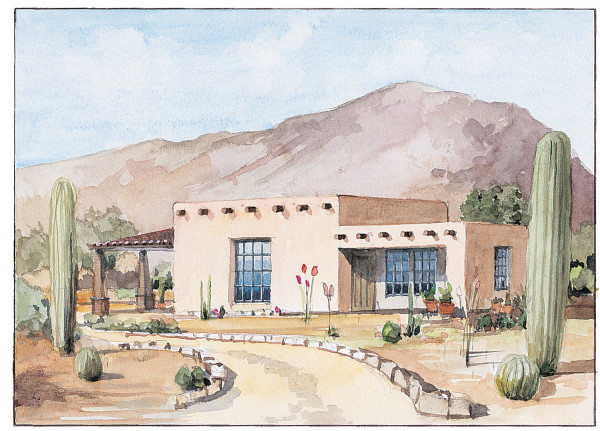

Spanish Colonial Revival illustration.

Rob Leanna

The first wave, however, beginning near the end of the 19th century, was based on California’s historic mission churches (1769–1823). Designers and builders adapted recognizable bits from adobe church buildings, most notably the mission dormer or roof parapet (think of the Alamo). Baroque ornament and the mission bell tower made their appearances. Given to long arcaded halls, bigger than life, Mission Style was popular for such commercial and institutional buildings as schools, fire stations, and railway depots. A common motif is, of course, the red tile roof.

The Spanish Colonial Revival style that followed was, in certain parts of the country, both nostalgic and suited to the climate. Inexpensive stucco could be applied to concrete blocks (or even a wood frame); indoor–outdoor rooms and exterior hallways made sense. Interior courtyards figured into the new emphasis on family privacy.

Decked out in white stucco with roofs covered in red clay tiles, one-storey Spanish Colonial bungalows fill entire housing tracts in California and Arizona.

Douglas Keister

The style was popular not only for one-storey bungalows (please, call them casitas!) and single-family homes, but also for housing complexes. Transplanted Midwesterners Arthur and Nina Zwebell settled in Los Angeles in 1921, where they decided to develop courtyard apartments. With no formal architectural training, they ended up setting the standard by producing such landmarks as the Andalusia (1926), a startlingly beautiful, intimate, asymmetrical complex built around a lush courtyard.

Heavy corbels support the mantelshelf in a 1934 Spanish ranch.

Courtesy Chronicle Books

This was a vigorous and interpretive revival. Besides Mission and Pueblo, there is a Monterey style (second-floor gallery porch), and a Moorish strain. Those courtyard apartments borrowed details from the Iberian Peninsula. Many houses—and movie theaters—might be better described as Hollywood Spanish. The booming 1920s was an era of exceptional skill—in such trades as plastering, blacksmithing, masonry, cast-stone and terra-cotta moulding, and tilemaking—enhancing the creativity.

Unlike California bungalows and Cotswold cottages, the Spanish Revival style never completely went away, even after the Depression and World War II. Santa Barbara, for one, has stuck with Spanish Colonial as a guideline since the 1920s. Another revival started in the 1960s: the first Taco Bell opened in 1962.

Spanish Interiors

Arched openings between main rooms, rough plaster walls, and wall niches recur. The era’s middle-class houses often were built around a simple bungalow plan; it may be that only rough-troweled plaster or Spanish or Moorish tilework in the entry is a clue to style. Neutral plaster and, sometimes, a beamed or wooden ceiling conspired to produce monastic rooms. Floors are often of waxed tile or wide oak boards. Iron is used for hardware and grilles, stair rails, or lighting fixtures.

Decorative metalwork in a 1920s house by California architect Richard Requa.

Gary Payne

Interior decorating was eclectic, running from a spare Mission aesthetic to Jazz Age color and luxury. Like so many revival homes of the time, furnishings were a pleasant mix of the vernacular with conventional American standards. Period photographs of the finer houses reveal carved and painted wood ceilings, tiled interior and exterior patios, antique furnishings from Spain, and imported wrought-iron light fixtures. Yet in the living room there might be wing chairs, in the bedroom a Victorian walnut bedstead. Tile, painted accents, and fabrics brought vivid color. Moorish patterns are often in evidence. Rustic, wicker, iron, and Mission/Craftsman oak furnishings fill out many rooms.

Mission Revival (1882–1915)

Mission Revival illustration.

Rob Leanna

The earliest wave grew out of a preservation movement that began in the 1880s. Designers and builders adapted easily recognized motifs from early Spanish–American adobe church buildings in California. Look for red-tile roofs and smooth stucco accompanied by curvaceous “mission” parapets or dormers. Spanish Baroque ornament may decorate walls or door surrounds. A “bell tower” appears on some examples. Also popular for theaters, civic buildings, and railroad stations, the Mission style had lost momentum by 1920.

Pueblo Revival Style (1910–1940)

Pueblo Revival Style illustration.

Rob Leanna

Distinctly Southwestern, it reflects a fusion of Native American and Spanish Colonial architecture with the characteristics of centuries-old adobe construction. Pueblo houses typically feature thick, smooth, light- or clay-colored stucco walls with round or blunted edges, and flat roofs with projecting vigas (hand-hewn roof beams), hidden behind low parapets. Doors are usually planked or paneled; windows often have lintels. Stuccoed chimneys are often integrated into the overall mass of the house. Pueblo Revival style was most popular in Arizona and New Mexico, where variations are built today.

The Malibu-tile fireplace and stenciled coffered ceiling are original in a 1926 Spanish bungalow.

William Wright

The Hallmarks:

- A BLOCKY ASYMMETRY suggests naïve construction using adobe bricks. Massing is broken by penetrations and projections: look for arcades and balconies.

- A COURTYARD, or the semblance of one, is standard. The house may enclose outdoor space or be C- or L-shaped. The loggia is a semi-enclosed room open to garden or patio.

- RED-TILE ROOF: It’s the essential characteristic. Half-round Spanish or Mission clay tiles are laid on flat or low-pitched roofs (gable or hip, or a combination), with little to no eave overhang.

- HALF-ROUND ARCHES are common for loggias, doors, and windows. Occasionally a wide and pointed or Moorish arch was used.

- A STUCCO FINISH is almost universal. It’s usually white, but clay- colored tan and salmon hues also are found.

- TILE AND IRON provide color and ornamentation on otherwise simple exteriors. Outside and in, woodwork is heavy and may be carved.

Paint decoration was based on that in Spanish missions.

Jaimee Itagaki