When she was a graduate student at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Lisa Harris fell in love with the Sam Hughes neighborhood. A square mile of picturesque adobe, brick, and red-tile roofs, it’s a National Historic District, named after 19th-century city leader Sam Hughes. Lisa couldn’t afford to live here as a student, but once she began working, she started house hunting. Her parents’ weekend hobby was designing and building homes, so Lisa had grown up amidst hammers, sawhorses, and blueprints. Renovation was in her dna, so she wouldn’t mind a big project requiring heavy lifting.

The entry tower is new; the original 1940 house is to the left. William Wright

Built in 1940, the little house of stucco and red barrel tiles was nestled in a quiet cul-de-sac. Lisa was intrigued: it was set on a double corner lot, but had obviously been through hard times. Owing to a prolonged divorce, the house had sat vacant for several years. The lights didn’t work—wiring was both faulty and decaying. The original, mammoth gas furnace was, the building inspector told Lisa, an explosion waiting to happen. Carpeting was ripped and filthy, the stuccoed interior walls were cracked. Oak floors had rotted over subflooring infested with termites. Most of the appliances had been removed and the blackened bathtub was unsalvageable. The landscape consisted of a dying citrus tree in back and a long-dead lawn in front. An addition holding three bedrooms and two baths dated to the 1980s, with access through the carport. It was so underbuilt, a flushing toilet could be heard from outside.

Offering a grand welcome, the entry hall occupies one of three new rotundas added to the house. Lighting is a mix of antiques and reproductions. The new, circular entry hall sits in a soaring tower. Exposed pine beams and the warm paint color Flemish Gold Suprema (Kelly Moore) create a Southwest ambiance. William Wright

Lisa reminded herself that she was an experienced remodeler. She did not know that the project would take nearly two decades and eventually involve lawsuits, two different architects, a change in contractors, two kitchen designers, and a decorative painter with a serious drug habit.

The enlarged dining room was created from the former kitchen and dining room in the old house. The heirloom Civil War parade flag dates to ca. 1862. William Wright

She began with demolition, working on the house every weekend for a year, enlisting the help of friends with work parties. Lisa ripped out mildewed carpeting, plywood kitchen cabinets, and the rotted floors. She cut down a thick vine growing into the house through a crack in a porch window. Lisa had hired an architect to plan the renovation, but that designer told her she was moving too slowly and could never afford what needed to be done.

Arts & crafts meets Spanish ironwork in the design of three ca. 1910 copper lanterns in the living room. The living room in the new addition has exposed beams and ca. 1910 copper and mica lanterns overhead. Vintage pieces include a 1960s Ferris wheel found at the Paris flea market. William Wright

So Lisa found another architect, who understood the vision. A new foyer, living room, library, and master bedroom would replace the flimsy addition. The original 1200-square-foot house would be enlarged by enclosing the back porch for a new kitchen. Floors would be leveled and rotted windows replaced with period-style, crank-operated casements. In honor of the street name (and inspired by a picturesque house across the way), Lisa also would add three rotundas: for the entry hall, for a library, and as an adjunct to the kitchen.

Construction began in 2002, just when Lisa had her second daughter. The 1980s addition was demolished and the new wing begun, on schedule. At the same time, craftspeople worked on the original 1940 space, retiling bathrooms and cleaning up the exterior. Original barrel tiles were salvaged and used along with new tile.

Then . . . work ground to a halt.

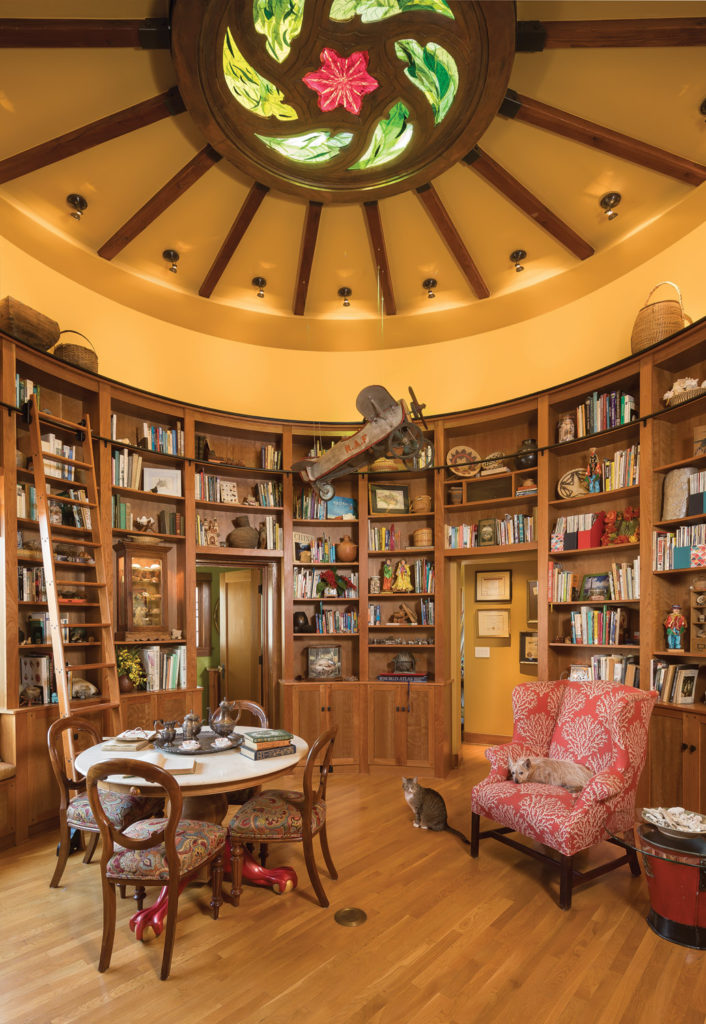

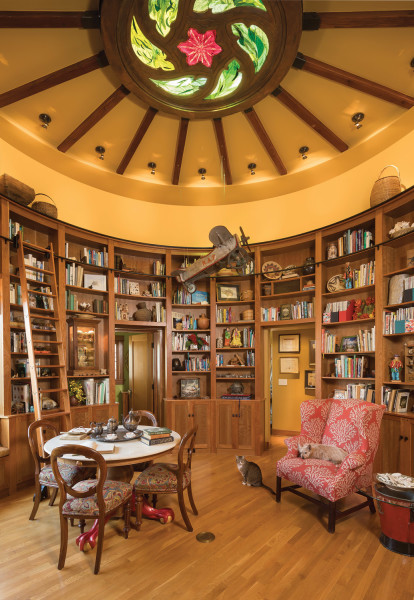

The circular library was the last project, completed in 2016. Custom, curved cabinets in cherry were made on site, using a wood steamer made from an oil barrel. Library cabinets were made by Kligian Woodworks; each section has a different arc. William Wright

The contractor had made a series of mistakes, his subcontractors even more. Kitchen ceiling beams were cut incorrectly, the crawl space was unvented, floors in the new addition were two inches lower than those in the house. The rotundas were improperly roofed. As lawsuits were settled and a new contractor enlisted, the house sat for six months ringed by construction fencing, black plastic tarps covering the new roofs as weeds grew in the yard. Lisa admits that friends stopped asking her for trade referrals. And plans for quarters over the garage were scrapped when a neighbor complained that guests would be able to see into their backyard, where she liked to skinny-dip in the pool.

Older daughter Lyda created a girl’s fantasy bathroom with bubblegum-pink walls and a river-rock floor. Aqua and marine-blue tiles are from Santa Theresa Tile Works. William Wright

With a competent and sympathetic contractor in charge, mistakes were corrected and projects finished. The new addition refocused the house; the circular entry room is now a grand affair in a central, two-storey rotunda. A master bed-and-bath suite opens off the living room with its vaulted, beamed ceiling. The circular, two-storey library was the last project. Its ceiling centers on an antique teak window from India, into which art glass was fitted to create a skylight.

The kitchen gained height and volume with a 13-foot rotunda over the dining area. Beams converge in a center soffit. Custom cabinets are veneered in cherry. William Wright

Now Lisa turned to interior finishes: kitchen cabinets, an Arts & Crafts tiled fireplace in the family room (in the 1940 section of the house), newly stuccoed walls painted in a Southwestern palette. Bathroom fixtures include a glass sink designed by Lyda, Lisa’s older daughter, who at the time was just 13. Lyda chose the river-rock flooring, Santa Theresa tiles, and Papaya Punch pink for the walls. Where the original kitchen and dining room had been, the new dining room has oak flooring and a built-in buffet with a granite counter from a U.S. quarry. The new kitchen is at the back of the house, where once there was a patio and sunroom.

The original house was restored but also extensively enlarged—with three rotundas added. The yard was landscaped with plants native to the Sonoran Desert, including velvet mesquite and Texas ebony trees, and several varieties of cactus. William Wright

The yard was landscaped with velvet mesquite and Texas ebony trees, varieties of cactus, summer poppy, desert marigold and primrose. A pair of Sonoran desert tortoises happily inhabits part of the yard.

Sonoran tiles

Company sign for Santa Theresa Tile Works. William Wright

Except for the fireplace, tile in the house was made by Santa Theresa Tile Works, a unique company that has supported Tucson youth and artists since its founding by artist Susan Gamble in 1986. It’s named for the saint Teresa de Avila (b. 1515), reflecting the company’s female ownership and a Spanish heritage. The brilliant tiles and mosaics are found all around the city. Customers choose from a standard collection or create their own mosaics. There are tile-making workshops as well.

In 2016, Gamble handed the company’s assets over to Imago Dei Middle School, a tuition-free private school for fifth- through eighth-grade children from low-income families. santatheresatileworks.com

Building a Rotunda

- FORM In this house, cement blocks were cut into chunks and placed to create a curve. The outside walls were plastered, forming the arc.

- INTERIOR Very simply, narrow widths of drywall were cut and placed in an arc, then smoothed with drywall compound and given a textured stucco finish coat.

- WINDOWS Narrow, flat windows from Marvin were placed together to form the arcs.

- MOULDINGS Wood moulding was steamed to make it pliable, then bent to shape and nailed immediately to prevent cracking.

- CEILING & ROOF Both ceiling and roof were “cut” into symmetrical pie-shaped wedges. Inside, exposed wood beams created a framework that was filled with drywall triangles.

Resources

contractor Craig Coryell, Tucson Design LLC

library cabinets custom Klijian Woodworks

interior paints walls Papaya Punch, Flemish Gold Suprema Kelly-Moore Paints • LR walls Country Estate: Dunn Edwards Paints

fp tiles ‘Mission Lily in Caribbean Blue and Lee Green glazes Motawi Tileworks

bath tiles Aqua and Marine blue tiles Santa Theresa Tile Works