During the 20th century, the parlor ceiling was removed to expose the ancient ceiling beams. French doors were installed in the most recent renovation.

Photos by Michael J. Lee

Boston’s North Shore boasts an unrivaled collection of First Period houses. Built by the English who settled the area in the 1600s, these generally pre-1725 structures were heavily timber-framed of locally available hardwoods and, with hewn and pegged joints, followed the traditions of medieval English construction. Many originated as single rooms with upstairs lofts, later becoming saltbox and center-entry houses as additions stretched to the rear and side.

“When we began work on this house, it seemed to me that it had originally been a two-room house, with one room downstairs and one above,” says Bob Weatherall. A builder in historic Ipswich, Massachusetts, Bob is well known for timber-framed structures, including barns.

“But I love good architecture from all eras,” he says. He does admit that the houses dating to the First Period are special—rare historic artifacts of a way of life we can’t even imagine. “I think that the original house, built in 1670, was added to early on, because in the attic you can see the gable end with the old clapboards still on. And, in the room they call the parlor, there’s a pair of adjacent posts and a difference in floor heights. It indicates that a half-house was built, and then another house was moved and attached to it.”

Bob thinks this house might originally have had a medieval European roof: “This is one of two houses in the area, built during the 17th century, that has the steep roof pitch required for thatch.”

The oldest room is used as the dining room. Sally Wilson chose its furnishings to provide a warm backdrop for winter holidays.

Weatherall has known this house since he was young, when he was a schoolmate friend of the current owner, who grew up in the house. Facing the two-lane country road that was once the main highway between Colonial towns, it is backed by fields that border a vast salt marsh. Like most rural First Period houses, it’s accompanied by a barn and a cluster of outbuildings. The lady of the house speculates that its roadside location once had the house functioning as an inn. Weatherall repeats a story that says a late 18th-century owner was a British soldier who stayed behind after the Revolutionary War. Neither legend has been verified, but, as with all houses this old, tales abound.

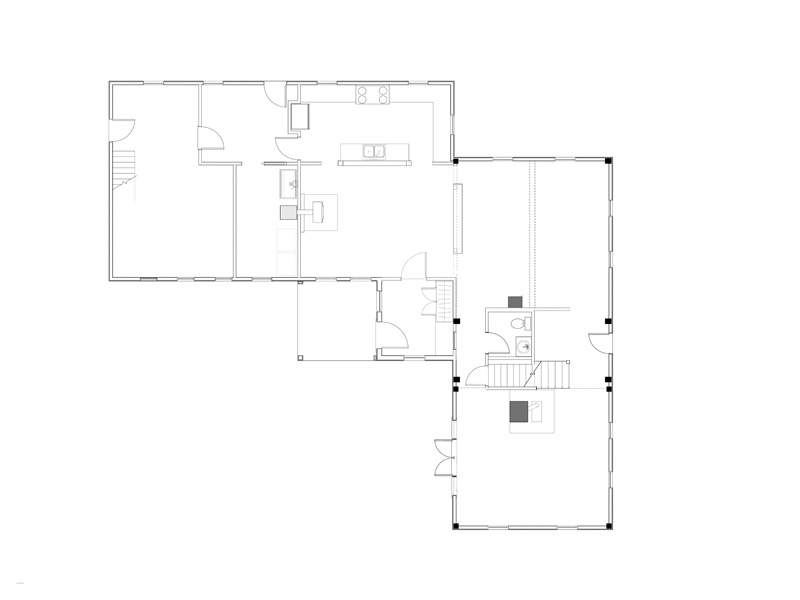

As much as the owner loved his childhood home, he and his wife wanted to introduce some 21st-century function—and they had to repair serious damage done over the years. The convenient rear doorled through a warren of spaces including a woodshed, a storage room, a mudroom, a decaying bathroom, and a convoluted hallway. The large center chimney and its encircling staircase, a standard feature of these houses, was gone, likely the result of a fire around 1900. A rear kitchen addition had resulted in one of the girts being notched, weakening the structure. In the dining room, the summer beam and one of the tie beams were gone.

“The old frame suffered from that long-ago fire,” Bob Weatherall says. “Various additions over time resulted in a dysfunctional interior layout.”

The house’s ancient entry is a battened door, constructed of vertical planks. The battened door opens to a paneled interior door (seen on p. 12). Today, family and friends drive into the backyard and come in via a back door. The owners asked Weatherall to create a functional rear entry, to strengthen structural elements, to replace the bathroom rotted by long-term water leaks, and to connect the main living spaces to the outside. For interior design expertise, they hired Sally Wilson, asid, of the firm Wilson Kelsey Design, who have offices in Boston and Salem.

“Bob was working on the back when he and the homeowners realized they needed help making the circulation work,” says Wilson. “The initial plan called for a full bath, but it was awkward and space was tight,” she explains. “A half bath would be gracious for guests while leaving space for a family mudroom.”

The homeowners celebrate holidays in the dining room, leading Wilson to use saturated terra-cotta reds and olive greens for the drapery and upholstery fabrics. Because the old central stairs are gone, the dining room will always function as a pass-through, she points out. “We chose a very rugged rug for that reason.”

In the parlor, neutral tones harmonize with the exposed ceiling beams that dominate the room. Wilson chose the best pieces of antique family furniture and re-upholstered several, including a bun-footed sofa for which she designed a new camel back. She found space for the family’s two wood stoves, and lighting fixtures sympathetic to the old house.

“What’s most important is that now the flow makes sense: they can walk from the parlor to the back door,” Wilson says. “And the new French doors in the parlor mean you can step out to the grill without having to walk all around the house, inside and out.”

“The aura of a 400-year-old house is special,” Wilson adds. “Nobody wants to live in 1670, but we do want to preserve character and any original structure. We made the interior fresh and welcoming.”

Landlocked

The new rear entry and mudroom are adjacent to a landlocked half bath—

it has no exterior walls for a window. To introduce light, Sally Wilson designed a custom casement window that opens from bath to mudroom. (The fabricator is Shards Stained and Etched Glass Studio, Peabody, Mass.) The new window’s diamond-paned leaded glass suits the 17th century house, which may well have had such windows at the start.